From the shearing shed to the art gallery — how Ken Marting carved out a life as a sculptor

FROM the shearing shed to the art gallery — how Port Lincoln’s Ken Martin carved out a life as a sculptor with works from his home town to the Adelaide Oval and beyond.

KEN Martin never went to art school. Ken was a shearer. A good one. He could knock over 150 sheep in a day, and, in a good year, he and his shearing partner could strip the fleece from more than 40,000 animals. At the end of a backbreaking day he would retire to his spartan shearers’ quarters, with no TV or even a radio, and he’d draw to pass the time.

This was Martin’s art school — the isolated sheep farms of South Australia’s upper South-East. You can see it in his work, informed by the Australian bush and the people who live in it.

Now one of the country’s most sought-after sculptors, Martin has, through hard work and raw talent, risen from a bloke carving in his back shed to make ends meet to the artist charged with immortalising some of our sporting greats in bronze.

Barrie Robran, Jason Gillespie and Darren Lehmann at Adelaide Oval, and the full scale sculpture of three-time Melbourne Cup winner Makybe Diva on the Port Lincoln foreshore are all his. Not bad for a kid who left school at age 14.

“For a long time I think I was a little bit self-conscious about being self-taught,” Martin says over a schnitzel and a pint of Coopers in the front bar of the Exeter Hotel. “But really, being self-taught is just a different means of learning. The source of the knowledge is the same. If you can read you can source the information.”

Martin was the son of a farmer and shearer, and looked destined to follow in his father’s footsteps. He worked on his uncle’s farm in Tintinara before picking up shearing in his late teens and earning 18½c for every sheep shorn. He averaged 150 sheep a day.

Through hands-on labour he became familiar with form, and through helping to butcher animals for food he learned about anatomy.

“I enjoyed shearing, and in focusing on becoming a good, clean shearer you have to study the form of the sheep, or at least be conscious of it,” Martins says. “You also develop a manual dexterity, and there’s that focus on the tools and the craftsmanship of it. You have to make sure your tools are sharp or you’ll go nowhere, so I suppose there were certain disciplines within shearing that did carry on to sculpting.”

His night time drawing evolved into sculpting, first with the malleable Mt Gambier stone and then with wood. Despite the fact he was surrounded by hardworking, no-nonsense country men, Martin says there were “one or two blokes” who were encouraging of his art.

“It was only when I started to become more serious about it and started talking about retiring from shearing that they started asking questions,” he laughs.

Martin’s first chance to turn his art into a career came when he teamed up with master craftsmen Bernie Koker and Malcolm Averill with the aim of establishing a furniture factory in, of all places, the Eyre Peninsula town of Port Lincoln.

“Constantia was my first opportunity to work professionally,” he says. “There were a lot of discussions about where to locate at the time, and a couple of practicalities came into it. One was the cost of setting up in the city, and the other was that, at the time, Port Lincoln had the most vibrant economy of any regional centre. Another factor was that in the South-East you had radical climatic changes that weren’t good for wood — in the morning you’d have frost and in the afternoon it might be 110 degrees, so you’d have warping and cracking and splitting.

“Port Lincoln is almost like an island — it’s surrounded by water and has a constant relative humidity that makes it ideal for working wood.” Constantia furniture was a hit, and it put Martin — who carved all the intricate detail — and his fellow craftsmen on the map. “This idea to develop furniture design influenced by the Australian bush — but in a very refined way — captured people’s imagination,” Martin says.

He left Constantia in 1986, an event he describes as “the band breaking up”, and decided it was time to have a crack at sculpting fulltime. “When the partnership disbanded I had to look at where I was going from there,” Martin says.

Thankfully Lisa — Martin’s wife, mother of their two boys and fellow visual artist — backed him. “It is scary, particularly when you’re broke! It was challenging,” he says. “I think Lisa was probably the bravest person I know, just to say ‘yes’ to it.”

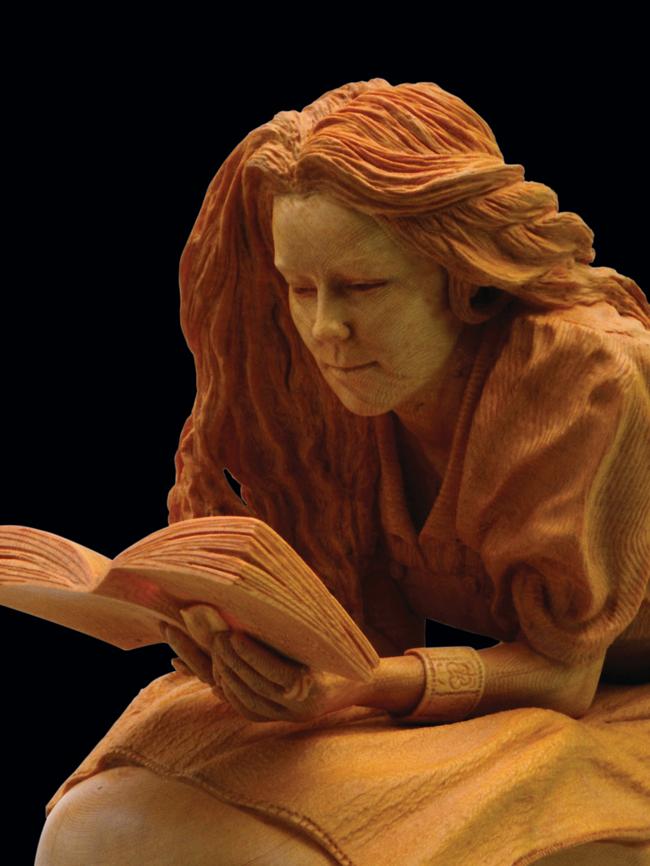

Martin started carving his intricately detailed wood pieces from his humble back-shed studio, and word began to spread that there was an artist in Port Lincoln doing world-class work.

“There was a visitor from England who was fascinated by what I was doing and he collected two or three pieces,” he says. “He submitted one of those pieces to the Royal Academy of Arts in London on my behalf and that was accepted in the Summer Exhibition of 1992. That was quite a credential, if you like. And, similarly, there was (Canadian steel baron) Russ Edwards, who commissioned a portrait of himself, so there was starting to be a little bit of international interest.”

Along the way Martin began incorporating more organic forms into his work, abstract yet immediately familiar pieces inspired by the Australian scrub and the animals that live in it. “It probably grew out of that period making furniture and interpreting the form of the bush — the bark and leaves,” Martin says. “I’m fascinated by this notion of symbiotic relationships in nature, how all life on this planet is interdependent and how if you upset one aspect another will fall away.”

Martin eventually moved away from wood, due partly to potential health hazards in the dust he was creating. “A lot of the rare exotics have toxins in the timber to protect them from parasites, and when you carve them you release that in the dust,” he says.

“Ivory wood from the Clarence River, for example, if you’re careless with that you’ll end up with a severe earache for two hours. There are even a couple that can have a very bad effect on your testicles!”

He moved into brass, then landed the commission that would change everything — a life-size portrait of three-times Melbourne Cup winner Makybe Diva to stand proudly on the foreshore at Port Lincoln, the home town of the horse’s owner and local tuna baron Tony Santic. “Makybe was the first, and quite a major piece in that it got a lot of media attention because of the subject, because of who Makybe Diva was,” Martin says.

“The thing with public work is that there’s always this catch 22 in applying to be involved in that you need the credentials — either through your education or your track record in producing public work — to show that you can do it. So I was very fortunate that I had the support locally to get Makybe Diva up. To capture a horse properly is challenging, but I relished the idea of it.”

Martin immersed himself in George Stubbs’ 1766 masterwork Anatomy of a Horse (“I really don’t know if that’s ever been surpassed”) and spent time with the mighty mare, photographing her and getting to know her.

Half a tonne of plasticine was sculpted over a steel and wire armature and the end result was nine huge pieces of horse in bronze that had to be expertly welded together to show no joins.

It turned out beautifully, and Martin now had runs on the board in the competitive field of public sculpture. It led to him being one of the artists chosen for the Adelaide Oval sculptural series, funded by philanthropist Basil Sellers. Jason Gillespie firing down a rocket, Darren Lehmann dispatching a ball to the boundary and Barrie Robran taking a screamer are all his, and they kept him busy for years.

After being his own boss for so many years, Martin suddenly found himself working in collaboration but it was a challenge he relished. “My main satisfaction is being able to have continuity of work, that’s what drives me,” he says. “And there is a satisfaction in doing these big public pieces, but there’s also a lot of responsibility. It could be around for hundreds of years, so you don’t want to make a mistake. I feel privileged to do it. It’s nice to hear people say, ‘Let’s meet in front of Barrie Robran’.” ●

Ken Martin: Sculpture, Imprints Booksellers, Hindley St, city, imprints.com.au