Former PM Malcolm Turnbull says he would love to still be in charge

A new book by Malcolm Turnbull has sparked a firestorm, but the former prime minister is unperturbed and holds forth on his former colleagues, his battle with depression and saving ship building in SA.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Malcolm Turnbull reveals how he saved SA’s economy in new book A Bigger Picture

- Christopher Pyne: I’m still Malcolm Turnbull’s mate and it surprises me his biggest critics are from the political right

- Malcolm Turnbull’s publisher threatens to call in Australian Federal Police

- How to get the most from your Advertiser digital subscription

After it all. After all the pain, the heartache, the rejection, even the depression and the thoughts of suicide, Malcolm Turnbull wishes he was still in politics. Wishes he was the one guiding Australia’s response to the biggest global health crisis in a century, and not his successor as prime minister, Scott Morrison. A man, perhaps not surprisingly, he never really trusted.

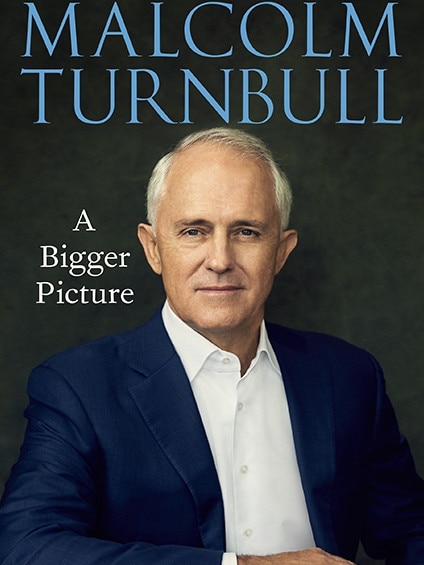

Turnbull’s recollection of his time in politics, plus his other careers in journalism and business was released this week in a 700-page book he called A Bigger Picture.

It’s fair to say it caused a bit of a stir. A firestorm erupted, that proved that in the 20 months since Turnbull was removed from the nation’s top job, none of the bitterness and rancour felt by his many enemies on the Right of the Liberal Party has evaporated.

Even before the book was officially released, Turnbull’s publisher Hardie Grant was threatening legal action against a staffer in Morrison’s office for distributing a leaked electronic version of A Bigger Picture. Then a member of the NSW Liberals proposed a motion that Turnbull should be given a lifetime ban from the party. So much for freedom of speech.

Over a Zoom call, Turnbull chuckles at the reaction from his enemies, not only within the party, but also from sections of the media.

“They love to hate me. It’s a Pavlovian sort of reaction,” he says referring to the famous experiments by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov, who conditioned dogs to respond in a predictable manner to certain stimulus.

Yet, for all the furore, he still misses his old job.

Asked if the current COVID-19 pandemic was a good time not to be in charge, given all the stresses and strains, the sleepless nights and impossible decisions leaders all over the world are currently facing, Turnbull is unequivocal in his response.

“I would much rather be in government trying to handle these problems than not,” he says.

“I would relish the opportunity to be in office and be able to ensure Australia emerged from this as unscathed as possible, but I’m not. That is someone else’s job now.”

Still, the 65-year-old believes Australia has done a good job in dealing with the crisis. Not only the Federal Government, but the state premiers as well, mentioning South Australian premier Steven Marshall.

He doesn’t offer any criticism of Morrison. He does believe the cruise ship industry should have been shut down earlier, but that was a mistake that governments around the world made.

Turnbull is supportive of initiatives such as the $130 billion JobKeeper wage subsidy program that pays $1500 a fortnight to eligible employees of businesses struggling through the pandemic.

In some ways it’s not surprising Turnbull would still like to be in the midst of the hurly-burly of government. He may be reluctant to criticise Morrison, but there’s no doubt he would fancy himself to do a better job than the man who was treasurer in his government.

Call it ego, call it confidence. Turnbull has never lacked either. He sees himself as a problem solver. Whether that was in business, law or politics. In the business world he acted for billionaire Kerry Packer, he took on the British government in the “Spycatcher” trial and won, made tens of millions in business and, despite his eternal internal battles in the Liberal party, he became prime minister.

He discounts the idea he wrote A Bigger Picture as a square up against his old enemies. It is, he says, just the chance to put down his version of history.

And that as a one-time prime minister, it’s his duty to do so. “I think that if you … have been prime minister of Australia, you really owe it to the country that you led to set down a history of your time in office,” he says. “It’s an important contribution to history. Obviously some of it will be contentious, people will have different views, but that’s what history is like.”’

There is no doubt it’s contentious. Turnbull hasn’t spared too many feelings in detailing his rise and fall as Liberal leader, both in opposition then in government.

His predecessor Tony Abbott, his successor Scott Morrison, Home Affairs minister Peter Dutton and Finance minister Mathias Cormann all receive a savaging at different times.

Leadership challenging

He recounts his emotions the day he challenged Abbott for the leadership in 2015 and walked out into a courtyard at Parliament House to announce his intentions.

“I felt like a great weight was being lifted off my shoulders. Serving in the Abbott government had been painful, humiliating, embarrassing all at once,” he writes.

“Cleaning up the messes created by his lack of discipline, trying to rationalise or temper his latest weirdness … I felt like I needed to take a shower some days just to wash off the indignity and taint of being part of such a shambles.”

He also wrote Abbott was driven by “hatred, fears, prejudice – anything negative”.

About Morrison he writes, while they eventually worked well together, he didn’t trust him because of his tendency to leak to the media. He also writes Morrison was “brittle emotionally and easily offended”.

Of Dutton, he wrote in his diary as speculation swirled that the former Queensland cop was counting numbers to challenge for the prime ministership that he “is very loose and imprecise, he lacks the intellect and discipline that he needs to perform at the highest level, very woolly”.

But perhaps, it’s his disappointment in Cormann that stands out the most. Turnbull was clearly wounded when Cormann, whom he considered a friend, turned against him to back Dutton. Three weeks after the coup which installed Morrison, Cormann wrote to Turnbull, denying he was part of the insurgency and expressing his sorrow at how it all worked out. Turnbull wasn’t buying it.

“Mathias, at a time when strength and loyalty were called for, you were weak and treacherous. You should be ashamed of yourself.”

Turnbull believes he was the victim of the “tribalism” of politics. Cormann was a member of the Right of the party and that counted for more than any loyalty to the prime minister.

In all this, of course, it is the vexed issue of climate change that lies at the dark heart of Turnbull’s downfall. It was the issue that propelled Abbott to defeat Turnbull in 2009 to become leader of the opposition and it was the ultimate driving force behind his demise in 2018.

Turnbull’s National Energy Guarantee, which was known as the NEG, had the aim of cutting emissions, bringing down electricity prices and improving the reliability of the grid. It had been through the Liberal party room twice but opposition to the plan, led by Abbott and including others such as SA MP Tony Pasin, ultimately saw the proposed legislation withdrawn. Days later Turnbull was out of a job.

The decision to withdraw the NEG still weighs on Turnbull and he tells SAWeekend “it’s a good question” whether he should have just tried to force it through. He says he ultimately didn’t because he was trying to hold the party together.

“I was in the position where it was obvious that there were enough members on our side who were prepared to cross the floor and vote against the NEG,” he says. “The cabinet was unanimously opposed to putting the Bill in until we had a better handle on whether we could get it passed. In those circumstances, as prime minister, how do you roll your own cabinet?”

The failure to implement a meaningful climate change policy is one of Turnbull’s big regrets. And he’s clear on where the blame lies.

“The key message on energy is you need engineering and economics, not ideology and idiocy, which is what you get from the Right and indeed to some extent from the Far Left,” he says.

Critics of Turnbull claim he talks a good game but never really delivered. On two of his biggest crusades – climate change and republicanism – he ultimately failed. Turnbull counters that he led a reformist government, pointing to the legalisation of same-sex marriage and the Snowy 2.0 pumped hydro scheme, which could cost more than $5 billion.

He points to South Australia as another example. To the $50 billion Future Submarines program and the foundation of the Australian Space Agency. Turnbull says the state was at risk of falling down an economic hole when he became prime minister. The closure of Holden was looming, there was uncertainty about ship building and the state was saddled with the most expensive and least reliable electricity in Australia.

“Do you think if I hadn’t been prime minister you would have the naval shipbuilding industry you have in South Australia? I don’t think so,” he says.

“It was a very strong personal vision of mine that we had to have a substantial Australian defence industry and that we had to have continuous Australian naval ship build, as opposed to building the submarines in Japan, which was what (Tony) Abbott was seeking to do.”

In A Bigger Picture he even predicts the submarines could one day be converted to nuclear power.

“Do you think anyone else would have established a space agency? Or an innovation and science agenda?”

No regrets

Turnbull comes across as an optimist, but he also details how depression took him to some very dark places after Abbott replaced him as opposition leader in 2009. Of how depression “ambushed” him and led him to thoughts of suicide.

“It was such a significant part of my life and such a significant episode in my life, it’s not something I could skip over,” he says.

Turnbull said it’s important for “people who are high profile like me to be able to describe that personal experience”.

In his book, he includes a diary extract from the time: “The answer is the pain will end at some point – suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary (we hope) problem. But frankly I am thinking about dying all the time.”

After losing the leadership the first time, Turnbull announced he was quitting politics. He changed his mind and ran again at the 2010 election. Despite the hills and valleys he says he has no regrets. He would do it all again.

“I don’t have any regrets about going into politics at all,” he says. “And I certainly don’t have any regrets about my decision to stay in politics in 2010. But it is a very tough business, there is no doubt about that.”

A Bigger Picture by Malcolm Turnbull, Hardie Grant, RRP $55