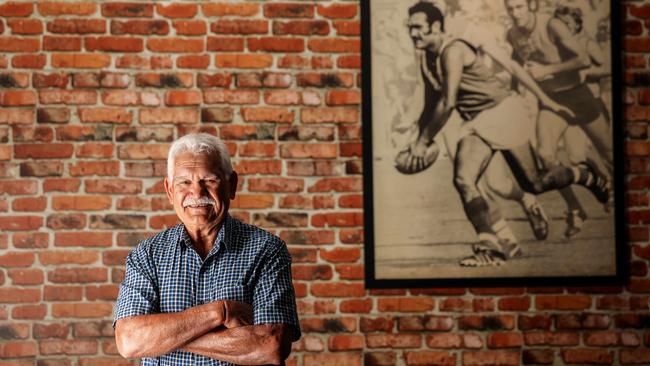

‘I’ve always believed I’m better than what the racists want to call me’: Why Sonny Morey has never given up

He was taken from his family from a creek bed outside Alice Springs as a child. This weekend, the footy champion and Indigenous leader walks on to the MCG.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

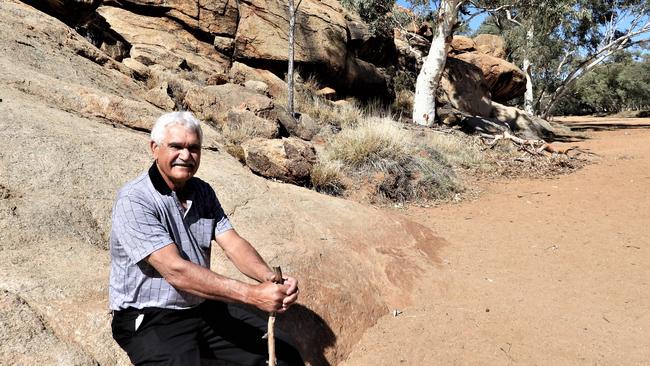

Sonny Morey fell in love with footy kicking a tennis ball around the creek beds of the Todd River, the arid waterway which stretches through the centre of Alice Springs, in a spot not far from where he was stolen from his family a few years prior.

He would play with his mates for hours, honing his speed, strength and endurance.

The small bouncing ball helped with his balance; soon he was proficient on both sides of his body.

Young Sonny had natural flair and he let it shine during those long hours among the sand and rocks.

He loved the game, loved the skill involved, and reckons those formative years laid a strong foundation for the long career to come.

“We used to kick a tennis ball around, and that really taught me skills in the game,” Morey says today.

“I’d even say to AFL players today, ‘kick a tennis ball around, you’ll kick a footy better’.”

He has an old photo with a group of footy mates from around that time; they were all boarders at the Australian Board of Missions’ St Mary’s Hostel in Alice Springs.

Whether it was a tennis ball or an old football cobbled together with rags and newspapers (the hostel couldn’t afford one with a bladder, he says), Morey says his passion for the game grew with every outing.

His voice is rich with emotion when recalling those early friendships.

“I can remember one of my teammates and I’ve got photos of these guys, 8-9 years of age … out of that photo there’s only me and one other fella still alive,” he says.

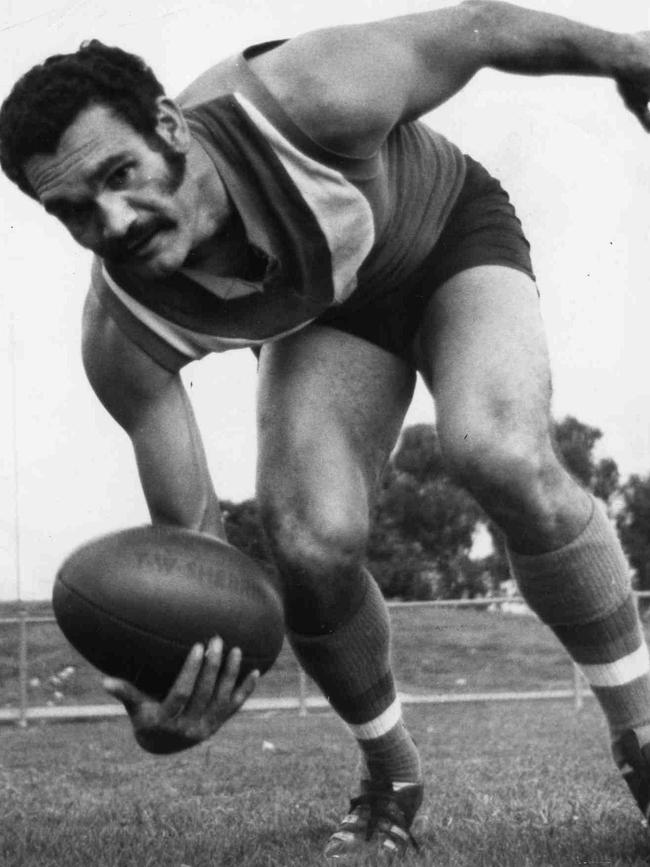

Morey would come to Adelaide as a 13 year old and, before long, talent scouts would notice the kid with the natural ball sense and silky skills, who seemed to grow an extra leg running through the wing.

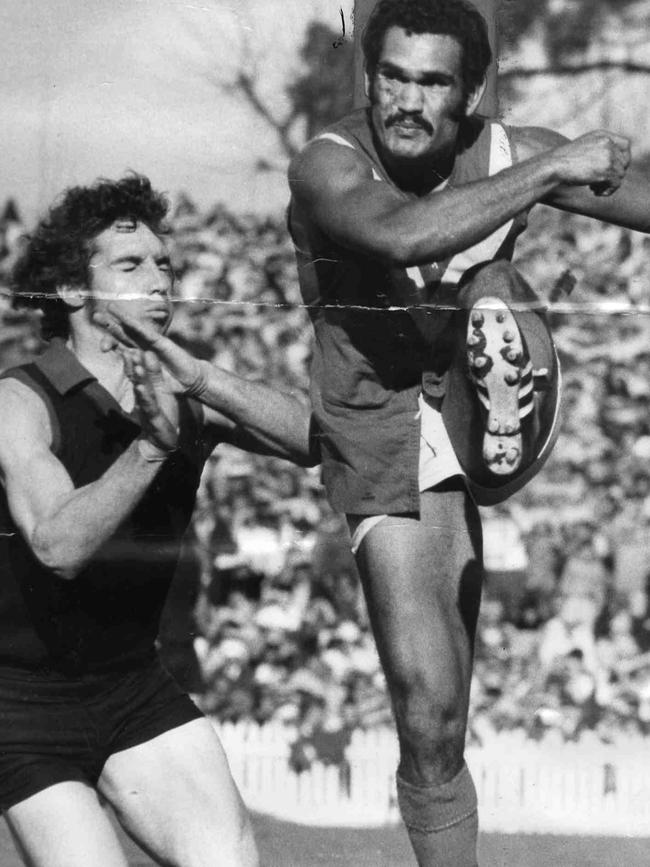

He would join Central District in its first year in the SANFL, going on to play 213 games for the Bulldogs.

He took out the best and fairest in 1970 and would finish second in the Magarey Medal count behind Malcolm Blight in 1972.

Only last year, he was inducted into the South Australian Football Hall of Fame and he is a member of the SANFL’s Indigenous Team of the Ages.

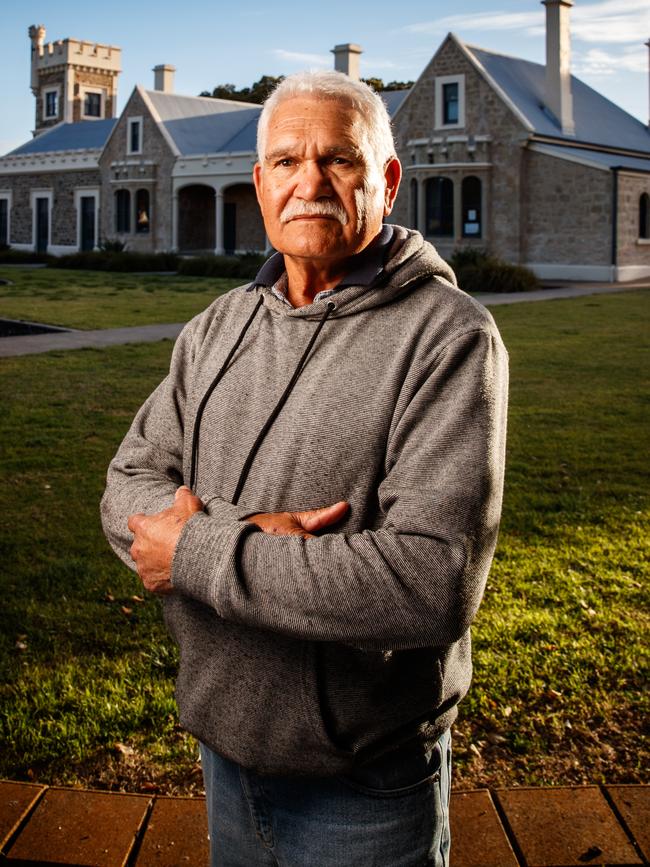

Now the proud Arrernte man has been announced as this year’s honoree for the annual Sir Doug Nicholls Round, and will be officially recognised at the AFL Dreamtime clash between Richmond and Essendon at the MCG on Saturday.

Morey says it is difficult to articulate the pride he feels for his family, his people, his culture, fellow members of the Stolen Generation, his teammates, his opponents and himself on a day that celebrates our First Nations players and officials.

“Plus,” he adds with a smile, “it’s nice that a non-Victorian is being recognised.

A second later his tone becomes a little more serious: “I think it means a lot for South Australian football, because my recognition is not just about me; it’s about where I played, who I played with, and even who I played against. To me, it means something for the whole state.”

FOOTY’S THE GREAT EQUALISER

When Morey started playing for Central District in 1964, he wasn’t recognised as an Australian citizen.

This was three years before the 1967 referendum that would finally see Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders counted as part of the population and treated as equals – at least in theory.

“I can remember times with my teammates, I’d be waiting outside because I couldn’t go into a hotel, because I wasn’t recognised,” Morey says.

Racism, he says, was everywhere.

He was called everything under the sun and is saddened to think it still goes on today. His response was to make himself bulletproof.

“Nothing’s changed. This racism rubbish is still going on from the time I was playing football. I got called some awful names. It didn’t worry me. I was more determined to succeed and do better every time I was called names,” he says.

“I said to myself ‘I want to be above this racist rubbish’ and I’ll prove it, and I think I’ve done that over the years.

“People have called me all sorts of names but that’s their problem.

“They’re the ones with an issue, not me. I’ve put up with it, but I’ve also always believed I’m better than what the racists want to call me.”

Racism, he says, is a byproduct of ignorance mashed with self-centredness.

You sense he feels more pity than anger for those who indulge in it and would rather focus on the many “very good people” in Australia who preach a message of tolerance and inclusion – a message he says got largely buried in The Voice debate.

These days, he’d sooner focus on what can be changed and what needs to be achieved. It’s why he has so much affection for what the game has given him, and what the Sir Doug Nicholls Round represents.

“I don’t know where I’d be without footy,” he says simply.

“Footy has always been a great equaliser in race relations, because I’ve always been treated as an equal when I’ve played footy.

“There’s no “i” in team and it’s everyone working together for a purpose. The friends I’ve made in football are my friends for life.

“And it’s the same when I coach the young men in underage teams, they come from all different parts of the state, they have huge respect for each other and they think very highly of me, which is nice when you’re an old coach and getting grumpy at them.”

It also gives him pause to reflect on the long journey that brought him to this point.

MY HISTORY, MY FAMILY

Sonny Morey was just seven when he was bundled into a government car while playing on the Todd River, under a policy which destroyed countless Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.

During an interview with SA Weekend in 2020, he described two strangers approaching him and his cousin, John Leo, on a balmy day in 1952.

He couldn’t remember much of what happened after he was thrown into that dark government sedan, apart from seeing his cousin crying as they drove off.

“From that point onwards, everything was just blank, because I was terrified,” he said.

“Over the years I’ve learnt to control that fear but that was just an horrific moment. I can still feel it now. It is a very unpleasant feeling.”

He was another victim of the raft of misguided government policies which a 1997 Bringing Them Home report estimated removed at least 100,000 Aboriginal children from their parents.

Morey became a ward of the state and for six years he lived in the Alice Springs hostel.

Then, in 1958, without warning or explanation, he and two other boys (Peter Butcher and Wally Gardener) were bundled into a plane and flown to Adelaide, arriving in another Board of Missions home charged with caring for Indigenous boys taken from their parents.

He would later move in with World War II veteran Sydney Maguire and his wife Ada in Gawler.

The couple already had three children but decided to take in Morey as their adopted son.

But Sydney was a drunk and a wife-basher, and Ada eventually summoned the courage to leave her abusive husband and moved with her adopted son into a house near the Gawler football oval, where Morey was already making a name for himself.

By the time he was 17, he had won two A Grade best and fairests at Gawler Central Football Club and in 1964, two weeks before his 19th birthday, was part of the first Central District SANFL league team.

He would retire 13 seasons later, in 1977 after 213 games, as the last remaining player from the original side and would be regarded as one of the true Indigenous pioneers of SANFL football in the 1960s, alongside the likes of Sturt’s Roger Rigney, West Adelaide’s Bertie Johnson, South Adelaide’s David Kantilla, and Port Adelaide’s Richie Bray and Wilfred Huddleston.

Today, it’s the close bonds forged during those very early years that stand out as much as anything.

“We all came down together,” Morey says.

“Wally is still somewhere in Alice Springs, I haven’t seen him for a long time.

“The story with Peter is he had a sister at St Mary’s and he didn’t know and his sister didn’t know. He came from up in the Gulf of Carpentaria. He passed away. He was playing footy in Alice Springs, got hit across the head and was killed instantly. This was some time ago.

“The interesting part is Peter’s sister, Peggy, who has since passed away, is the grandmother of one Lachlan Jones, who plays for Port Adelaide.”

It is emblematic of the close connections that bind the Indigenous players and their families across generations, he says, while recalling a recent function to celebrate Wilbur Wilson’s 70th birthday, where he struck up a conversation with the great Michael Long.

“And we find out that his family links are my links; neither of us could believe it. But those links go very deep, and they mean a great deal to us,” he says.

LEADER, ROLE MODEL, TEAMMATE, FRIEND

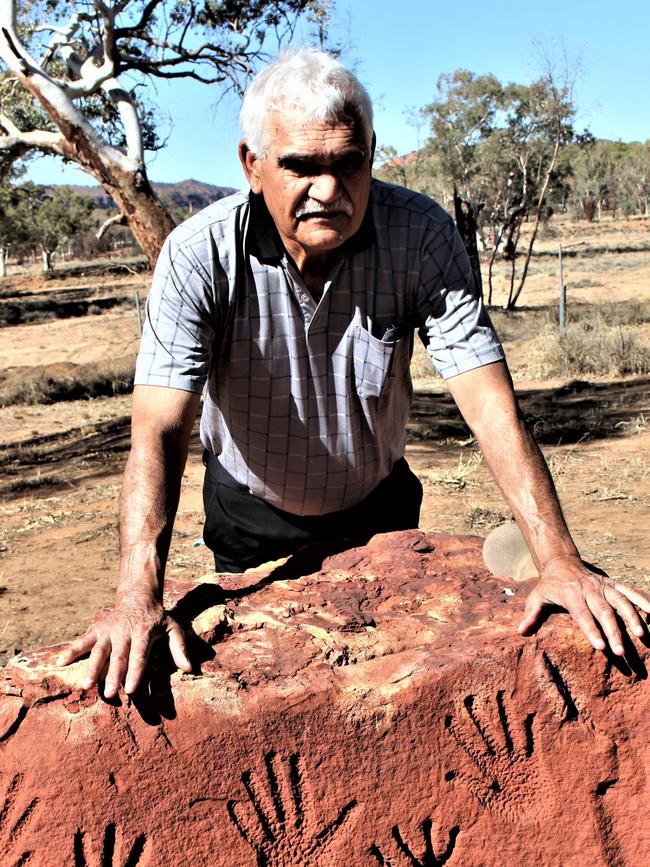

Morey has slowly come to terms with his traumatic childhood; a fairly recent discovery that his mother had searched for him for years in vain after he was taken softening long-held feelings of guilt and abandonment (he also visited Napperby Station, north of Alice, last year after learning his mother was buried there. He hopes to visit again soon and will aim to mark her grave).

With age and wisdom, he learned to redirect often confused feelings and emotions into something positive, firstly through his footy, then years of coaching, then in his work life, namely his 12 years spent with South Australia Police, largely in the northern suburbs and APY lands, where he worked closely with Indigenous communities and youth.

“As a young man I found it very painful and it was hard to reconcile the sense that it happened. Then I thought: ‘Hang on, I’m not the only one this has happened to. This happened to a lot of Indigenous people – a lot,’” he says.

“Then I thought I could be somebody who does something about these things, and that’s what I’ve done.

“I’m actually the first Indigenous patron of South Australia Police, and that makes me very proud.”

He has also been a mentor to a generation of young men, having coached Eudunda for three years following his retirement, in the process becoming the first Indigenous premiership coach in the Barossa and Light Football Association. He would subsequently coach Central’s under 17s for close to a decade.

These days, nothing fills him with pride more than the family he has built with wife Carmel, his partner of more than 50 years. Together they have two daughters, four grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

And they will be front of mind in a few days’ time.

“This means a lot, not only for myself personally, but for my family; it’s about who I am and where I come from,” Morey says.

“But it’s not just about my family. We’re human beings, we’re all family. We’re all on this planet for only a short time and if we don’t care for each other, we’ve got a problem.

“Family is the one thing that connects us and ties us to who we are. Without your family, you are nothing.”

A member of the Stolen Generation. A proud Arrernte man. A footy legend. An ambassador for his people, his community, his culture. A friend. A teammate. A role model. A father, grandfather and, now, great-grandfather.

Sonny Morey will carry all those tags and more as he strolls on to the MCG in front of a packed house next Saturday.