Floki, Lloyd and now Jax: A journey to SA Police

It’s been a long journey, with many new people and a few different names for Jax the german shepherd — the dog must have wondered if he would ever find a home. But then fate took a hand.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s been a long journey, with many new people and a few different names, but for Jax the german shepherd, it’s turned out well in the end.

Bought from a breeder by a young man who didn’t realise the time and space the energetic dog would need, the pup named Floki was first given to German Shepherd Dog Rescue South Australia, then a kind kennels operator – who renamed him Lloyd – and finally to the SA Police.

By then the dog must have wondered if he would ever find a home.

But then fate took a hand.

Landing a job with the SAPOL dog unit is the police equivalent of “being selected for the Australian cricket team”, according to Senior Constable Tony Potter, an officer for nine years before he was selected as a dog handler in 2009.

“It’s a hard gig to get into and it’s incredibly sought after,” Potter says. “We call it the best gig in the department.”

SAPOL’s dog handlers work a rolling five-week roster that includes daytime, evening and overnight shifts.

Though it’s the hardest on the body clock, the week of night shifts is the favourite for most handlers: crooks tend to be most active under cover of darkness, and the dogs’ incredible senses are at their peak when the sun goes down.

“The hours of darkness are the best shifts for us – we jokingly call night shift week our Grand Final week,” says Potter. “It’s the one week out of our roster that you really get to see the dog at its best.”

It was during a night shift in June 2014 that Potter’s then two-year-old dog, Ink, suffered the terrible injuries that ultimately led to his early retirement.

Ink chased down an offender during a 2.30am ATM robbery at a suburban shopping centre. The man leapt into a parked car and slammed Ink repeatedly with the door, leaving the courageous canine with broken ribs, a punctured lung and a ruptured disc in his spine.

Though he was back at work within three months, Ink developed degenerative arthritis in his spine and SAPOL decided in conjunction with vets to retire him sooner rather than later.

The man who injured Ink was the first person charged with causing harm to a working dog under tough new laws passed in December 2013.

Then his colleague, Simon Rosenhahn, suggested Potter take a look at the young german shepherd called Lloyd. When he met Lloyd, he was cautiously optimistic.

“He was a little bit skinny. He was quite light, like a greyhound, but he had a good frame – I could see that when he filled out a bit he’d be a big dog,” he says. “He was a high-drive dog. He had plenty of energy, and unless you channel that energy it can be quite a handful.”

But when Lloyd came into the Thebarton barracks and went home with Potter (all police dogs live with their handlers) that cautious optimism became outright excitement.

“Within 48 hours of having him at home I said to my wife, ‘He’s a keeper’. Straight away there was just something – I can’t quantify it, it’s just that little 1 per cent you see in a dog,” says Tony.

Rosenhahn already knew that Potter and Lloyd would make a formidable policing partnership. So it was official: Lloyd and Potter would be a team. The first thing Potter did was change his new dog’s name. He couldn’t imagine himself shouting it in the dead of night as his jet-black dog pursued a villain. He decided on Jax.

“I prefer short, sharp and shiny names,” he says.

In March 2018, Jax officially became a police dog, whose key tasks include searching, locating offenders and engaging those offenders if they don’t comply with police instructions. Depending on the situation, that engagement might include chasing, cornering or even physically restraining a person.

“It’s all about human odour. We’re basically looking for people that are trying to avoid the police, and they go to great lengths to hide themselves. The dog is a great tool – we almost don’t need eyes, because the dog will sniff them out,” Potter says. Though he was still only a year old when he graduated, Jax wasted no time hitting his stride. Much of his work relies on his powerful scenting ability, but Jax also has another weapon in his arsenal.

“Jax has these massive, bat-like ears. His hearing is absolutely incredible – he can hear a pin drop 200 metres away,” says Potter. “I would never pick up on a slight rustle of someone behind a bush, but he will drag me off to a location and I’m sure he hasn’t been following a scent.”

Just as Potter picked up on that unknown “something” when he met Jax, he says that moment when his dog zeros in on a target has a similar intangible magic about it.

“Police dogs are hunters, and german shepherds have a distinct genetic design to do this. Jax’s body language changes when he starts to get into hunt mode. You can watch it build. If he gets a little hint of a scent it’s hair-on-the-back-of-the-neck stuff. If that person is on the move and going yard to yard, when the dog gets that whiff he’ll pull me out of my boots.”

The unofficial motto of the SAPOL dog squad is “Trust your dog”.

Even the most seasoned police officer feels trepidation when looking for potentially dangerous offenders, especially in the middle of the night, but a dog handler’s trust in his canine counterpart is absolute. That’s why the bond between dog and handler is so crucial: the dog’s protective instincts can mean the difference between life and death.

“I’d be a liar if I said I didn’t feel fear or anxiety. There are a good number of times, especially if it’s a crime of violence or you’ve been informed the offender may have a weapon, where you think, ‘It’s just me and my dog out here’,” says Potter.

“Your dog won’t let you down. If Jax is barking at that door or that industrial rubbish bin, I trust him. When [the offender] comes out it’s just a sense of joy: I’m safe, the dog’s safe, the dog has done this thing for me and together we’ve done this thing for the community.”

When a police dog collars a crook it’s known as a “win”.

Jax’s first arrest came just two months after his graduation, when he located a man hiding in bushes on a building site in Adelaide’s eastern suburbs.

The man was carrying a torch, bolt cutters and gloves, and was subsequently charged with being unlawfully on the premises and going equipped to steal.

Around the sixth month of their pairing, Potter says “it was like the penny dropped” for Jax.

At the time of press, the crime-fighting crusaders had more than 20 wins under their respective caps. Given the twists and turns in his life so far, it’s easy to forget that Jax is still only three years old. Potter believes police dogs hit the peak of their abilities around the age of five, so Jax’s best years are truly still to come.

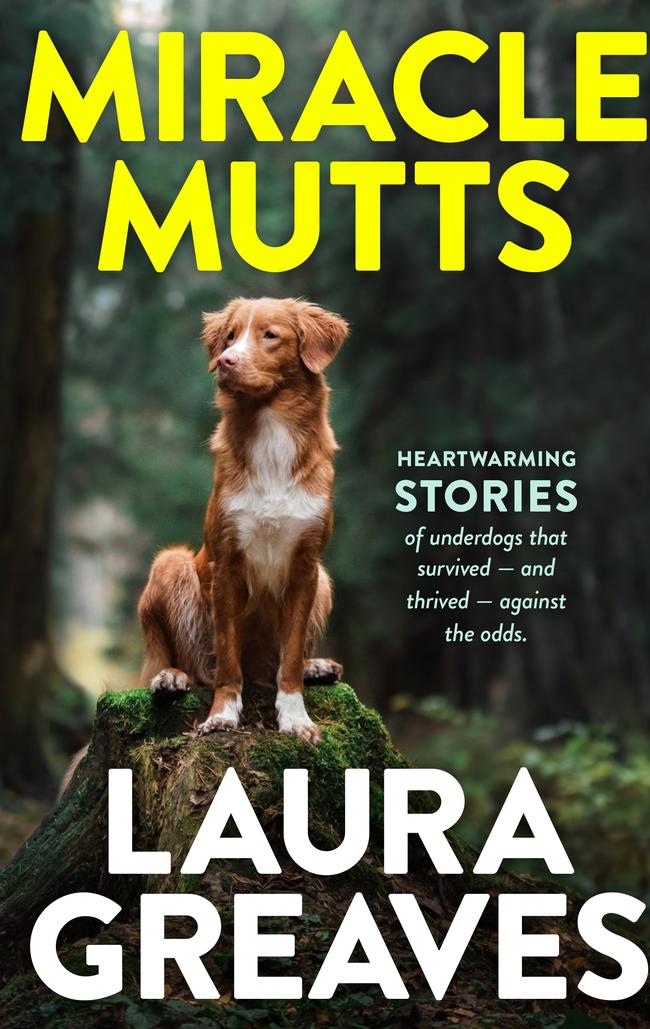

Edited extract from Miracle Mutts by Laura Greaves, published by Michael Joseph, $34.99. On Nov 18, Greaves will be at Tea Tree Gully Library.