Erin Phillips shares her defining moments

Erin exclusively opens up to SA Weekend about a secret she has kept for more than a decade.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Sixteen-year-old Erin Phillips stands in front of her wardrobe mirror, scissors in hand, looks at her stomach and contemplates.

A strange thought has popped into her head.

She can use the scissors to cut her belly. Someone will have to sew it back together, and when they do, they can flatten it out at the same time. Give her a tummy tuck. And then maybe, just maybe, she can learn to love her body.

Because she hates her stomach. And her legs, for that matter. She especially hates the way she looks when she’s squeezed into the bodysuit she’s forced to wear on the court.

And since she’s already well entrenched in Australia’s national basketball program, she’s been subjected to countless skinfold tests that reinforce her belief that she is cursed with a

pot-belly stomach and puppy fat.

It is, of course, a ridiculous self-assessment.

Phillips is one of the most exciting young basketballers in the nation and will soon carve out a life as a globetrotting elite athlete before returning to her home town of Adelaide and becominga pioneering women’s footballer.

But right now she’s looking at the scissors and sees a solution.

Sees a way to make herself happier.

And so she wonders if she should cut into her stomach.

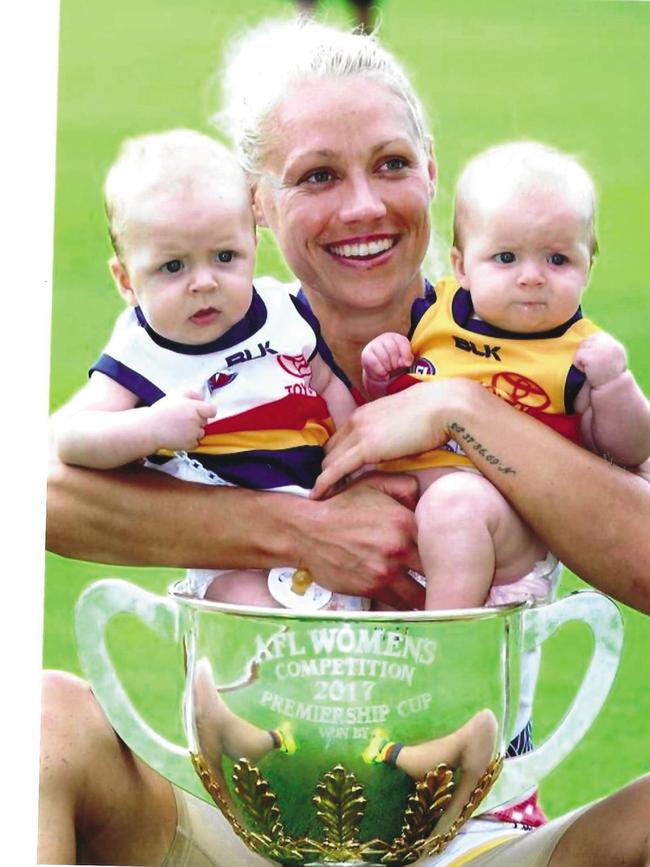

More than two decades later,we’re chattingat the dining room table in Phillips’ newly renovated home in Adelaide. Her wife Tracy, 44, is with us and their daughter Londyn, 18 months, plays quietly in the living room with her grandmother (Phillips’ mum Julie). Phillips and Tracy’s three other children (twins Blake and Brooklyn, 8, and Drew, 5) are at school.

We’re here to discuss Phillips’ autobiography, Inside And Out, in which she reveals the extent of the loathing she had for her body, especially in the early days of her basketball career.

No one, not even her wife or mother, knew the story of her 16-year-old self in front of the mirror with the scissors until it came out in the book writing process.

Phillips never followed through with the idea of putting the scissors to use on her stomach, but admits to years of unhealthy obsessing over her body and devising ways to rid herself of an abdomen she despised.

“(Former Australian of the Year) Taryn Brumfitt says it beautifully, that you have to appreciate your body for what it can do and not what it looks like – I was always the opposite,” she says.

“I was always being reminded of how my body is looking because I’m (playing basketball) in a bodysuit. It’s there for everybody to see. There’s nothing to hide.

“And I just became really obsessed with how I looked in terms of, like, I wanted to be leaner.”

Phillips concedes her stomach would have looked perfectly normal to others, but in her eyes it was bloated and a source of shame.

“I would have such skewed thoughts on how I looked, and would just wish that I could remove it myself,” she says.

“There was nothing that I could do that I thought was working. I tried diet pills and unfortunately they did work in many ways, which was a terrible thing.

“I was not eating properly. I was starving myself for so many meals. Not eating enough. It wasn’t a healthy way to be.

“I’m really lucky that I came out on a better end of it. Because there are so many stories of young people that go through body image issues and then have body dysmorphia or skewed thoughts about themselves.”

Now a few months shy of her 40th birthday, Phillips concedes being kind to herself has never been a strength.

She became an expert at a young age of maintaining a facade of focused calm regardless of any internal anxiety or turmoil.

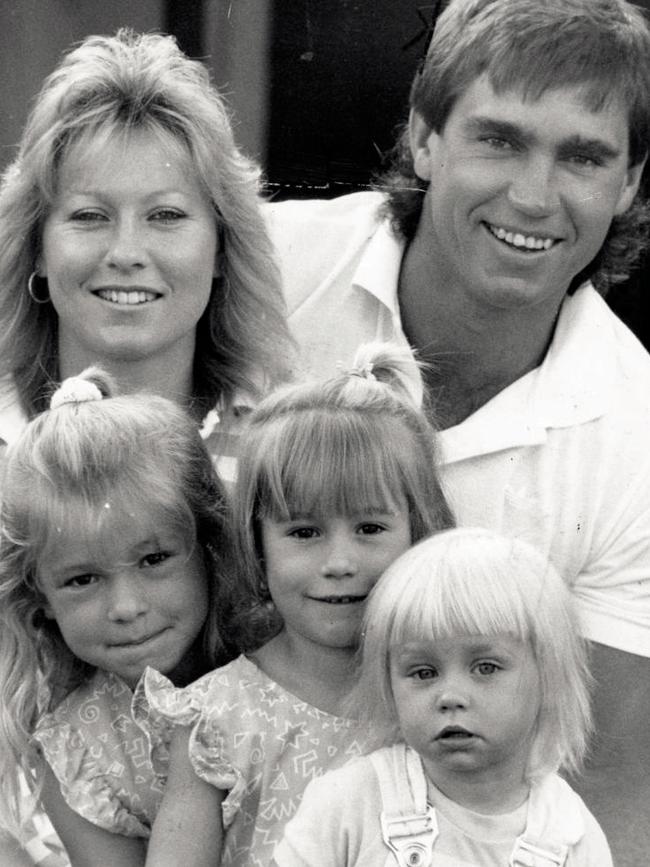

The third daughter of Port Adelaide Football Club royalty Greg Phillips, her early years playing football against boys has become part of South Australian sporting folklore.

Legendary Port Adelaide coach John Cahill has described her as being one of the best

14-year-old footballers, male or female, he has ever seen.

She was the only girl in her under-13 side at SMOSH West Lakes and won the team best and fairest award the year that Brett Ebert, offspring of another Port Adelaide great Russell, won the same award in the under-14s.

Brett Ebert would go on to kick 240 AFL goals in 166 AFL matches for Port Adelaide. Erin Phillips, meanwhile, was cast aside because of national regulations stipulating girls over 13 must stop playing with boys – despite there being no girls’ sides.

She now describes her exclusion from footy as “the biggest form of sexism of her life”.

At the time, she says, she adopted her standard coping mechanism of blocking out and bottling up the confusion, anger and sadness.

It is a method she employed often in primary school, where she was a proud tomboy sometimes confused for being a male by relief teachers or footy spectators.

At school, she was often told to leave the girls’ change rooms, where other kids looked at her as if she was in the wrong toilet. Some girls, who did know her gender, would tease her that the boys’ toilets were next door.

Her anxiety around toilets at school came to a head when she was about 10 and decided it was too traumatic to use the bathroom. Instead, she would just “hold on” for the entire day.

“I was busting, and my bladder finally got the best of me,” she writes in her memoir. “I was sitting in the classroom on one of those old orange plastic chairs and I literally weed myself.

“I sat there in my soaked shorts until the last student had left the room, desperately hoping no one would see what I was hiding beneath me.

“My only saving grace was that I had a jumper with me that day and wrapped it quickly around my waist as I stood up. I got home from school, went straight to my room and cried.

“I was so upset and angry at myself for caring so much about what others thought of me … I vowed then that I was never again going to let what others thought of me impact who I was or the decisions I needed to make for myself.”

But that’s not to say her teenage years were all rainbows and unicorns. Far from it. She admits to feeling a lot of resentment about being a girl, was beginning to question her sexuality and had been forced out of the sport she loved.

After her exclusion from football, she transferred her energy and dedication to basketball but her rise through the ranks ultimately led to the bodysuits and skinfold tests that played a huge role in the body image issues and undiagnosed eating disorder that would haunt her for years.

Erin Phillips, mother of four, can’t believe she once thought of cutting her own stomach and says she wants to “hug the younger me” and say sorry.

She was so conscious of how her stomach looked in the figure-hugging bodysuit worn by national women’s team the Opals that she resorted to diet pills, fasting on match daysand the zero-carbohydrate Atkins diet.

One year, while living in Dallas in her mid 20s, she dragged Tracy to an appointment with a specialist she hoped to convince to perform a tummy tuck.

“I knew she was being ridiculous, but I had to be there to support her and let a professional tell her she was being ridiculous,” Tracy says thoughtfully as we continue the conversation about body image. “Because she’s never going to believe me. I’m always going to tell her she looks good.

“And so to sit there and have the doctor basically be like: ‘You’re out of your mind – I can’t operate on you,’ for me, it wasn’t even like, ‘See, I told you so.’ It was just like, ‘All right, so let’s move on now.’”

Phillips says that was the moment the penny finally dropped and she started to respect and accept her own body. She remains conscious of consuming healthy food (she eats a plant-based diet that excludes meat, eggs and dairy) but can now enjoy popcorn and ice cream with the kids without a second thought.

She’s still up early each day to exercise before the morning chaos of preparing young children for school but is conscious of never posting images of herself wearing a bikini or crop top – not because she is anxious about her stomach, but because of the message it sends to others struggling with their own body image issues.

“I definitely had an eating disorder and I think there’s so many young girls out there that have eating disorders,” she says.

“And I grew up in an era when there was no social media, so I can’t even imagine how hard it is now.

“That’s why you won’t see me posting bikini shots – because it’s not relevant and it’s not important. I’m very conscious of even the language we use around our kids – and not just our girls, but our boys as well – about what our bodies can do, not what they look like.”

Regardless of self doubts about its size and aesthetics, Phillips’ body allowed her to reach unparalleled heights in her two chosen sports.

She made her professional basketball debut for the Adelaide Lightning in the WNBL when she was just 17 in 2002 and in her six years with the Lightning was a league all-star three times and a part of the team’s 2007-08 championship.

Her basketball career spanned 15 years and included two titles (with Indiana Fever in 2012 and Phoenix Mercury in 2014) in the best competition on the planet – America’s WNBA. She also starred in competitions in Israel, Poland and Slovakia – and says living and playing in those countries made her a better player and a better person.

Phillips was a member of national Australian teams that won gold at the Melbourne Commonwealth Games and Brazil world titles in 2006.

She achieved a lifetime dream of representing Australia in the Olympics at Beijing in 2008 and was a joint vice-captain of the Opals eight years later in the Rio de Janeiro Olympics.

She was captain of the newly formed WNBA team the Dallas Wings in 2016 when word filtered through from home about the AFL establishing a national Australian rules women’s competition.

Her dreams of following the footsteps of her father and representing her beloved Port Adelaide were dashed when the Power declined to bid for an inaugural licence.

But a phone call from Adelaide Crows’ football manager Phil Harper set the ball in motion for the daughter of a Magpie great to become the AFLW’s first genuine superstar – wearing the tri-colours of Port’s despised cross-town rival.

It’s a big call, but there’s an argument to suggest her name is now revered in Crows’ history as much as her father’s is at Port Adelaide. She steered the Crows to three of the AFLW’s first five premierships and personal accolades included two league best and fairest awards, two grand final best on ground medals and two club champion gongs.

She ruptured her ACL in the third quarter of the Crows’ 2019 grand final win against Carlton in an injury she describes as the lowest point in her AFLW career.

There was hardly a dry eye among the record-breaking Adelaide Oval crowd of 53,034 which rose as one to applaud as she was driven from the ground, fighting back tears. The moment remains one of the most iconic in Adelaide Oval’s storeyed history.

Fast forward three years, and this time Phillips is on the field when the siren sounds to secure the Crows’ 2022 premiership. She raises her arms in triumph before bringing her hands to her face and doubling over in relief.

As she joins her teammates’ embrace, she’s sobbing.

It’s an unprecedented level of emotion that most onlookers assume is sparked by the realisation this has been her last game for a club she has come to love. Port Adelaide is finally entering the competition the following season and most assume she will switch clubs to finish her sporting career where she started it, at Alberton.

And so the tears, the footy public assume, are because she knows she has played her last game for a team she has grown to love.

In reality though, she is weeks from making a decision on leaving the Crows and her football future is the last thing on her mind as the emotion overflows.

The tears are for a lost baby. For a heartbreak she and Tracy have kept secret from family and friends.

Less than two weeks earlier, four days before a preliminary final against Fremantle, Tracy had suffered a miscarriage. The baby would have been their fourth child.

“I cried because I was finally letting go and allowing myself to grieve,” Phillips writes. “I told Tracy that night after we’d won that I truly believe our little angel was there with me, helping me get through the game.”

The miscarriage is the nadir of a rollercoaster IVF journey the couple include in the book in the hope it can double as a resource for others embarking on a similar quest. Phillips says the idea of using their story to help others was one of the primary motivations for the book, ghost written by sports journalist Samantha Lane.

“Something Tracy and I are passionate about is helping people along the way with the IVF journey, and obviously being a same-sex couple, and the challenges we faced,” Phillips says.

“It made sense to go OK, a book is actually going to help people who are facing similar challenges. Sometimes people look at these athletes or high-profile people and think they’ve never had issues or they’ve never struggled or they’ve never had challenges.

“Everyone has challenges – you’re not immune to them no matter who you are. And Tracy was such an integral part of the story, and she encouraged me to tell it and to be open and honest.

“Calling the book Inside And Out was because it was getting to know me inside and out. Now obviously the ‘out’ part is Tracy and I, and our relationship.”

Coming out publicly about their relationship is one of many complicating factors the couple has had to deal with since they met and fell in love when Phillips was just 21 and a tall Texan called Tracy Gahan signed up to be her Adelaide Lightning teammate.

Phillips had previously been in a public relationship with former Adelaide Crow Ivan Maric but says she grew to know she was more romantically attracted to women than men.

An instant, close friendship between the two Lightning teammates quickly morphed into romance even though Tracy (who changed her last name to Phillips when the couple wed in Hawaii in 2014) says she had previously “never even thought about being with a woman”.

“We were from two different countries and we were both women – I wasn’t even sure that was something I was interested in,” Tracy says as the couple recall their early days at the kitchen table.

“And then there was something about her – the minute I met her, I was like, I’ve never felt this way about anybody before.”

Still, their road to wedded bliss was a rocky one. Tracy was 26 when they met. She had already travelled the world playing basketball and was ready for some stability.

Her younger teammate was just starting that phase of her life and was conscious of hiding their relationship both from the outside world and even those closest to them.

“I was never ashamed of Tracy because she’s the best, she’s my best friend,” Phillips says. “It was more the question of do we want to put up with all the outside attacks that would come our way as well.

“It was not just from a selfish point of view, but also from the point of view of protecting your family.”

Phillips says her number one priority at the time was succeeding as a professional basketballer and making the Opals’ 2008 Olympics squad.

She describes herself as being too “young and dumb” to handle the relationship and created a cycle of creating distance between the two of them, letting Tracy back in and then quickly pushing her away once again.

Juggling professional careers on different continents was an added complication but Phillips says her “selfish and immature” behaviour was to blame for Tracy running out of patience, ending their relationship and refusing to take her calls. It was a stage in their lives Tracy refers to as Phillips’ “arsehole stage”.

They laugh about it now, but Phillips was horrified when she realised her cold feet and uncertainty could force Tracy away permanently.

“That moment when I thought I had lost her forever was terrifying,” Phillips says.

“It was more terrifying than any of the challenges we would ever have to face together … It was almost like I grew up in an instant.

And so, after six years of on-again, off-again dating, the pair were finally fully committed and they married during a Hawaiian sunset ceremony in March 2014, only a few months after same-sex marriage became legal in the aloha state.

After splitting their time between Adelaide and Dallas for a couple of years, the couple and their young family are now fully entrenched in Adelaide’s western suburbs, where their daily routine revolves around preparing and delivering children to school and sport.

The children are involved in basketball, football, swimming and soccer. Phillips returned to her footballing roots and coached daughter Brooklyn at the SMOSH under-8s last year.

She also signed up to play and mentor juniors back at her first basketball club Woodville Warriors – though concedes the legacy of more than 10 knee operations has left her spending more time on the sidelines than on the court.

Phillips works for the AFL in its football operations team, concentrating on player and club engagement, and appears as an expert commentator for Channel 7’s AFL coverage on Sundays.

American-born Tracy has also fallen in love with Australia’s national sport. She is studying to become a player development manager with an eye on one day working at an AFL club supporting its young athletes.

The couple have just purchased a caravan and dream about driving it across the Nullarbor to give their kids the type of memories Phillips enjoyed as a child visiting her grandparents in Port Lincoln.

Phillips has come a long way since standing in front of her bedroom mirror with a pair of scissors as a 16-year-old, worried about the size of her stomach. By being open about their lives (she regularly posts family photos on an Instagram account with more than 70,000 followers), she and Tracy have become unobtrusive poster girls for same-sex relationships.

“There’s nothing scary about us,” Tracy says. “We’re just as boring as everyone else. We raise our kids the exact same way, get them ready for school, have little fights, and take them to sport on the weekends.

“It’s a love story that we got married, had kids and are just trying to figure out this crazy world just like everyone else.” â–