Eight South Australians who have stayed in their job more than 50 years

WITH more and more jobs falling to automation, and young people told to expect at least five career changes before they retire, it’s hard to imagine anyone in the future staying 50 years doing the same work. But these South Australians have.

WITH more and more jobs falling to automation, and young people told to expect at least five career changes before they retire, it’s hard to imagine anyone in the future staying 50 years doing the same work. But these South Australians have all spent more than half a century in their chosen occupations — and the secret, they say, is loving what they do.

JEFF WAIT, 68

Net Fisherman

Port Parham

Life-long fisherman Jeff Wait has just returned from a day on the waters of Gulf St Vincent off the coast of Port Parham. “Sixty kilos of garfish, nice big gardies,” he says when asked about the day’s catch. “Not too bad, but not as good as I’d like it to be, but that’s the way it is.”

The father-of-two got a taste for fishing as a 10-year-old on his uncle’s boat, and by the time he was a teenager he was crewing on a clipper.

“I started going out with a couple of Italian fishermen who sold fish at the Fishing Steps down at the old Jervois Bridge,” Wait says. “I left school at 16 and I’m 68 now, so yeah, I’ve been doing it for more than 50 years.”

Wait is a net fisherman, targeting some of the iconic South Australian species, including garfish, whiting and snook. Due to the vast tidal flats of the upper reaches of the gulf, the fishers use specially adapted tractors called jinkers — essentially a tractor on stilts — to get their boats to the deeper fishing grounds.

“Where I fish, we’re very tide restricted,” he explains. “In the other gulf they use net winches and wind the net on a drum and the tide doesn’t move as fast, so they might get two, three, maybe four shots in a day. Here we’re governed by the tide, and most of the time we get one shot per day.”

Commercial fishing, and net fishing particularly, has become something of a political football in recent years. Marine parks have made traditional fishing grounds in the top of the gulf off limits and, according to Wait, overregulation has made it impossible for fishers to plan a future.

“We are under a lot of stress all the time,” he says. “It’s not just my industry, it’s the rock lobster industry … it’s everyone.

“Every morning we wake up, we’ve lost something else. When I started fishing there were 600 net fishermen — there’s just 35 of us left.”

Despite the trials, Wait gets a lot from his life on the sea.

“I love my wife, I love my fishing and I love my hockey,” he laughs. “And I’ll prioritise them all in the right place at the right time.”

— Nathan Davies

FRANK BRIA, 70

Mechanic

Hampstead Gardens

Tinkering, tuning, and tightening cars has been Frank Bria’s world since his teens and he’s in no hurry to give it up despite more than 50 years as a motor mechanic.

The owner for the past 23 years of Frank Bria Motors at Hewer St, Hampstead Gardens, is the first one in and often the last to leave the business at night.

“At my age I should be retired but I still like to come to work and see what headaches my boys are going to give me and which customers are going to upset me,” Bria says with a chuckle.

Bria, who drives a Mitsubishi Pajero of a few years vintage, migrated from Calabria in southern Italy with his family aged 11 and settled in Norwood.

After a few years at St Joseph’s school on Portrush Rd, he worked in a family run deli but it was being selected for an apprenticeship at Krueger Motors, a Volkswagen dealership, that changed his life.

Volkswagens, and the classic Karmann Ghia in particular, remain his passion, but after completing the apprenticeship he worked 13 years with Holden dealership Freeman Motors, at the Maid and Magpie Hotel corner at Magill and Payneham roads.

He left there to start his own business, Frank Bria Motors, at a workshop at Magill. There were a couple of career detours, including driving a Woolworth’s truck for a year and pumping petrol, but the call of the tools was too strong.

“I’d do it all over again, to be honest,” he says. “I even love all the challenges and the bullshit that goes with it.”

Son Anthony, who has been on the staff since age 16 and has clocked up more than 25 years himself, says his father has always been a hard worker who is happiest out on the garage floor.

“He doesn’t like the office,” he says, “and talking to customers is not his favourite part of the business.”

— Craig Cook

LINDA CAMPBELL, 68

Midwife at the Lyell McEwin

Elizabeth

Linda Campbell has delivered thousands of babies over the past 50 years but one pregnancy, in particular, stands out.

It was the 1970s, before ultrasound became routine, and Campbell was helping a woman deliver her sixth child.

“I’d delivered the baby and looked at the mother’s belly and thought, ‘hmmm, that’s still quite big’,” Campbell recalls. “Out came a second baby — it was undiagnosed twins. It was quite a surprise for me, let alone the poor mother.”

Campbell still sees that mum occasionally — she’s now delivering her grandchildren.

Before moving to Adelaide with her parents when she was 15, Campbell saw the local midwife arriving on her bike through snowy Bristol streets to deliver her little sisters.

“I remember dad coming out to tell us it was another sister. There’s five of us altogether. It never occurred to me a brother might happen.”

She’s been at the Lyell McEwin long enough to see “a couple of babies” named after her, before her “name went out of style”, and to see the hospital morph from a “little country-style hospital” to what it is today.

“It’s really nice to stay in one place, it becomes like a little family,” she says.

But it’s working with women that continues to inspire Campbell, who every year wonders if this might be the one where she retires.

“The best thing about being a midwife is being able to support women in their choices,” Campbell says.

“I get to advocate for women and what they want. It’s lovely when you’ve worked with a woman in labour and she achieves what she wants it’s really nice.

“It can be quite stressful sometimes. It can get quite busy but it’s all worth it, it’s very rewarding.

“Every year I say I’m taking it as it comes. I’m still enjoying it, I think I’ve still got something to offer, there’s another couple of years left in me yet.”

— Elisa Black

ELAINE FILSELL, 69

Teacher

Semaphore Park

When Elaine Filsell began teaching at Gawler Blocks School in 1968, her pay slips showed the amount women were docked simply for being female and she was not allowed to wear trousers. In fact, she remembers it being a “scandal” when a female colleague at Hendon Primary wore a pants suit to a parent interview night a few years later.

Filsell, for whom Ocean View College is the latest of seven schools she has worked, also recalls classes of 40-plus students being common, while the idea of non-instructional time in the school day was “non-existent”.

“We did however have teacher aides who performed jobs for us such as copying worksheets on a Gestetner machine,” she says. “I have seen the introduction of decimal currency and metric measurement, equal pay, women being allowed to wear trousers, women not having to resign to get married or have children, computers and mobile phones.

“(But) the biggest changes I have experienced in education have been in the past five years. It has been like a tidal wave.”

She says that wave has been partly about technology, but more about the increasing data-keeping, reporting and accountability requirements teachers face.

Filsell says among her most cherished memories is the time a boy she’d taught in Year 3 and 4 invited her to his Year 12 graduation. “When I arrived there were flowers, chocolates and a lovely thank you card on my seat,” she says.

“A lady approached me two years ago and said that I taught her in Year 3 and now I was teaching her granddaughter in Year 3.

“(I met) a girl at a conference who told me I taught her in Year 3 and I was her inspiration to become a teacher.”

She says “it is hard to imagine a life without” teaching, adding “good health and lots of energy and loving my job are the reasons for my longevity as an educator”.

“I am still as dedicated as I was when I began my career, still putting in many extra hours before school, after school and at home at night,” she says.

“At every school I have taught I have made wonderful friends who also form my support base. I love mentoring younger teachers and caring for other staff members. My holidays are filled with meeting with groups of teachers from the many schools I have taught at.”

— Tim Williams

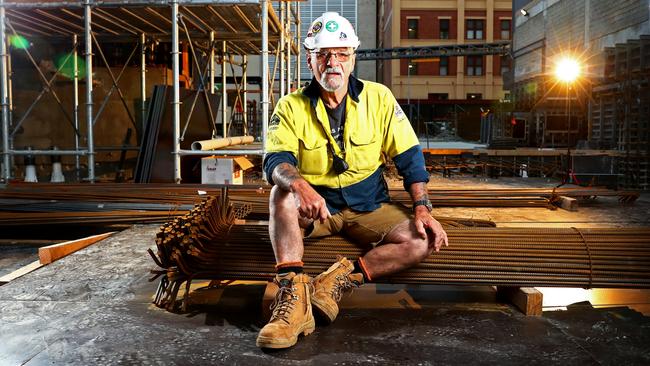

MICK HOPE, 69

Construction Worker

Semaphore

Mick Hope walks out of yet another funeral service — his second in a month. The construction worker of more than 55 years has come to the West Adelaide Football Club, in Richmond, to pay his respects to fellow rigger Ark Tribe.

Tribe, known nationally for a union landmark legal fight with industry watchdog Australian Building and Construction Commission in 2010, died from illness aged 56 in May — he was 13 years younger than Hope.

Hope says the bonds that tie construction workers are unbreakable. It’s why he’s lasted so long in a business which has high personal safety risks, little job security and favours the young and strong. “Yeah, it’s definitely the camaraderie of the crew,” he says. “We try and look after each other because they’re your work mates.”

Hope was born and raised in Buckinghamshire in southeast England. He was 14 when he started working as a labourer for the father of his teenage sweetheart and now wife Jenny. He’s since worked as a steel erector, crane operator and rigger in the merchant navy along the US east coast, on oil rigs in the Atlantic Ocean and Bass Strait, and across major building sites in the UK and Adelaide. “Working in the North Sea (off the UK coast) is the closest I’ve come to being killed — twice,” he says.

He made headline news as one of the Nicholas Bowater crew that helped pluck two survivors from a refugee ship of 45 when it sank off the coast of Florida in Hurricane Inez in 1966. Hope, Jenny and their three children migrated to Victoria in 1980 and three years later found themselves in Adelaide.

The long-term CFMEU member has helped build SA’s tallest building, Westpac House (1988); the Myer Centre in Rundle Mall (1988-91) just before the recession; the Embassy building on North Tce (2001); Port Adelaide’s New Port Quays (2007); the controversial Desalination Plant (2011); and a swathe of apartments that have built up the CBD in the last 10 years.

The grandad of seven and great-grandfather of four, says despite all the injuries and near misses, retirement is years away.

“I’m trying to beat my father’s record — he was a boiler maker who retired at 76. I just enjoy working — it keeps you fit.”

— Rebecca DiGirolamo

MARGARET NYLAND, 75

Criminal law

Adelaide

After a lifetime in family and criminal law, 25 years on the bench and two years as head of the Child Protection Systems Royal Commission, it is hard to take seriously how blatant the discrimination against women like Margaret Nyland once was. Yet in 1965, when she was admitted to the Bar, she struggled to find a firm that would take her as an articled clerk.

“They were candid, it was on the basis that I was female,” she says of the rejections.

“There was no point taking the time and trouble training women because they would just get married and have children and leave.”

Her father, a taxi driver, came to the rescue through one of his passengers, a lawyer and friend of the eminent jurist John Bray, who was her lecturer in Roman law at the University of Adelaide. “John said there was a girl in his firm that might be prepared to take me on and he arranged for me to see Pam Cleland,” she recalls.

Cleland, then a partner at Genders Wilson & Bray, left the following year to form her own Waterfall Gully practice which Nyland joined.

Later she became partner, and even later she took over the firm that in the early days had a strong clientele of gay men whose private relations were criminal. So “abhorrent” were these deeds, a magistrate tried to clear the court of women to spare their delicate feelings.

“The magistrate made the order and I was trying to make myself heard — I was very young in those days — and finally I said ‘I want to be exempted from the order’ and he said ‘why?’ and I said ‘because it’s my client, and I can’t represent him if you make an order that I leave the room’,” she says.

After years of difficulty planning holidays because of trial delays, her retirement in 2012 after 25 years on the bench, including 19 on the Supreme Court, brought an end to her life in the law. Well, almost.

Two years later she was back making her name as head of the Child Protection Systems Royal Commission and, more recently, as chair of the South Adelaide Football Club, another lifelong passion.

“There are a lot of people who are battling and they need some help,” she said. “You should do what you can to help them.”

— Penelope Debelle

RONALD KRUEGER, 68

Train driver

Ingle Farm

Even at 68 Ronald Krueger enjoys his job too much to give it away. And that’s not too surprising given he is still living the dream he’s had ever since he was a little boy.

Ronald Krueger is a train driver.

“Do you get bored? Nah.”

These days Krueger shunts trains for Great Southern Rail in Adelaide. He helps put together legendary trains such as the Indian Pacific, The Ghan and The Overland. Earlier in his career Krueger drove those trains himself, crisscrossing Australia from west to east, north to south.

He also guided massive freight trains, including the first ore train out of Broken Hill that weighed in at 6180 tonnes. Of course, he was always careful when in charge of that much moving metal, but admits to a slight bit more care when driving those long passenger trains.

“You have to be aware that you have a train full of passengers behind you and you have to make sure you don’t upset their wine or their soup,” he explains.

Krueger grew up around trains. His father was a ganger based at Sherlock, about 35km east of Tailem Bend on the Pinaroo line.

“The house was only a stone’s throw from the tracks at Sherlock, so I grew up next to the railway line.”

From Sherlock, the family moved to the railway town of Peterborough in the Mid-North, which is still a stop on the Indian Pacific line.

Krueger started working on the railway in Peterborough in 1967 when he was 17. He started as a “box boy” who would issue instructions to train crews. But he also studied and spent 250 hours shunting trains in the yard before he was allowed out on the main line.

Krueger has seen enormous change in the industry. The move from steam to diesel, from narrow gauge to standard and watched with sadness as many of the lines around South Australia have gradually been ripped up.

“You had railway tracks everywhere, all the (country) towns,” he says. “They were catered for by the railways and it’s sad to see that go.”

— Michael McGuire

JOHN TODD, 69

Shearer

Coonalpyn

John Todd can’t remember wool prices ever being higher than in recent months but it isn’t helping keep shearer numbers climbing too.

“Back when I was younger everybody on the properties would go out shearing,” he says from his own farm near Coonalpyn, 163km southeast of Adelaide.

“There were more sheep around in those days, a lot of the cocky’s sons used to go out and get a bit of extra money as well.

“There’s not as many around the district now, there’s hardly anyone; if it wasn’t for the Kiwis coming from New Zealand every year there wouldn’t be enough shearers.”

It’s been a good 52 years since Todd, who runs his own sheep on a 404 hectare farm called Kooreela, started in the line of work he would soon come to love.

He first picked up the shears as a teenager, at the tender age of 17, slowly learning the craft as a farm roustabout and gradually spending months at a time travelling Australia and working stints in sheep shearing sheds to supplement his own farm income.

Todd has worked on stations in Queensland, Broken Hill, in southern Victoria, Mount Gambier and in Western Australia, often meeting the same workers around the shearing circuit.

Now 69, he’s been working with a shearing contractor in Keith but has been set back by an operation a few months ago that makes it difficult to effectively clip the sheep.

“And the sheep are getting bigger and bigger, and the rams are getting bigger,” he says. “It’s got that way that you need a couple of people to get them out of the pen.”

But this long-time sheep farmer is philosophical when asked why he keeps the shearing up.

“When I first took the property on I had to make extra money so that’s what I did and then along the way I had a couple of divorces. I’ve got to keep shearing to pay the bills.”

— Belinda Willis