Eddie Betts: From bad boy to role model

EDDIE Betts admits he was headed for life on the wrong side of the tracks. But in a dramatic turnaround he’s become a star of the game — and his community.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

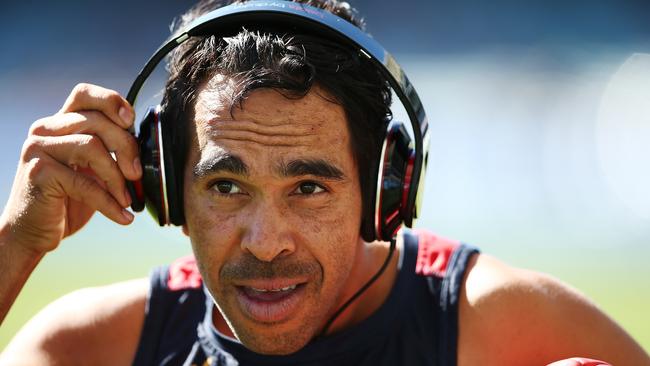

EDDIE Betts laughs with delight. On his phone he has found the footage of what he regards as his all-time favourite goal.

He kicked it while playing for Carlton in 2011. And it is a remarkable sight. Grabbing the ball near the goal line, he jinks, he jumps, he weaves. He leaves Essendon players entirely bamboozled before kicking it from a ridiculous angle while falling.

This one was so good that even Betts — a regular miracle worker on the football field — looks amazed by what he has just done.

Now with the Adelaide Crows, Betts has twice won the AFL’s Goal of the Year competition. Surprisingly, his personal favourite was only runner-up.

“I should have won,” he proclaims in mock outrage over lunch at a seafront restaurant in Port Lincoln, the town where he partly grew up.

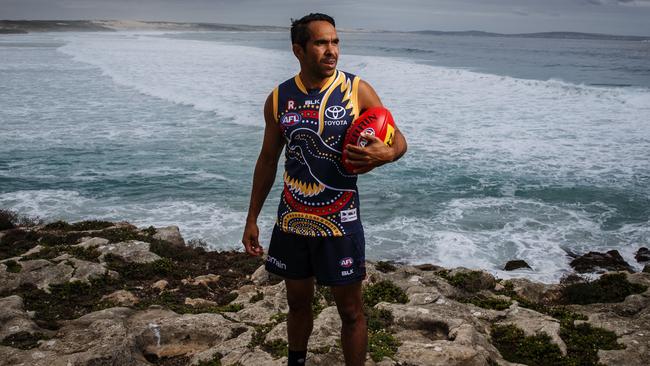

Betts is riding high. At the Adelaide Oval in front of more than 50,000 screaming fans he’s set to wear an Indigenous jumper designed by his Auntie Susan in a game against the GWS Giants. It will be a proud moment for Betts who, by his own reckoning, is in career-best form.

Not only is he adored by Crows fans, he is admired by just about every other footy follower in the country for the thrilling, daring way he plays the game. Even Carlton supporters still love him. Yet, it could all have been so different.

Betts is upfront when asked about what would have happened if he had not found his way to the AFL. “I could have been in prison, could have been in jail,” Betts admits.

“I guess playing AFL footy saved my career, my life. I wouldn’t have the family I have now. I wouldn’t be where I am right now.”

Betts’ early life was divided between Port Lincoln and Kalgoorlie, the gold-mining town in Western Australia. He moved to WA when he was about four after his mother Cindy and father Eddie Snr broke up.

But he moved back to Port Lincoln when he was 13 and found himself led astray.

There’s an endearing honesty to Betts. Asked to describe himself back then Betts doesn’t hold back.

“A little S.H.I.T. to be honest,” he says, spelling out the letters. He describes himself in those days as a follower, a yes man, tagging along with his older cousins as trouble beckoned.

“Thinking back now I don’t know how I could have made those decisions like ‘how could I break into that car’. I would never do that in a million years now. And break into houses. I thought it was normal.”

Betts loved and idolised his cousins, still does, and does not so much regret his past — “I enjoyed my childhood, growing up with all my cousins” — but acknowledges how far he has come since those days.

“I broke the rules. I did all the wrong things. Now I look back and I am a completely different person.”

Betts has his mother to thank for saving him.

Cindy Sambo returned to Lincoln from Kalgoorlie and saw her son’s life drifting on to the wrong side of the tracks. Perhaps, forever.

“She came across and saw me doing all these wrong things, she shifted me across to Melbourne, out of the blue,” he says.

“It wasn’t basically my decision. I wanted to stay. It was my mum.”

If being dragged from Lincoln imposed a hard-earned wisdom on Betts, it’s left a legacy that goes well beyond the football field.

Betts is now active in trying to reach and help Indigenous youth who risk slipping into a life of crime. He uses his own life story and experiences as an example of what is possible and why it’s never too late to find a new path.

Betts also knows how hard it is to change. He knows how hard it is to leave what he calls the “comfort zone” of a small, tight-knit community. He laments the wasted talent he has seen. The many Indigenous footy players with the ability to make it to the AFL but who lack the courage or resolve to venture into the big wide world.

“Most of these guys are talented and could play AFL footy but it’s just that committing to it and moving away and being out of your comfort zone,” he says.

His own father could have made it, he says, but family responsibilities kept him in Port Lincoln.

Still, it’s remarkable just how many AFL players have come from the same small part of the world that produced Betts.

We are walking through the clubrooms at the Mallee Park Football Club. Betts played for four years as a kid on the oval outside the window. On the other side of the sacred green space sits the “wombat pit” the scene of some of Betts’ happiest memories. It was a place where all would gather after a game to eat — wombat and kangaroo — and come together as a community.

Mallee Park is a remarkable place. It’s hard to think of another small community footy club anywhere in Australia that has produced as many AFL players. From the old ceiling hangs any number of premiership flags. Betts walks around the room and, almost with reverence, points out the old photographs of premiership teams, many featuring his father.

Above the bar hang pictures of all those who did make it to the big time. Betts is there of course, still wearing his Carlton jumper. There are Port Adelaide premiership players Peter and Shaun Burgoyne and Byron Pickett. There is Crows champion Graham Johncock, North Melbourne stars Daniel Wells and Lindsay Thomas. There is Derick Wanganeen and Harry Miller.

But Betts thinks there should be more.

He has long worked with Indigenous youth. In Melbourne he worked with White Lion in juvenile justice. In Adelaide, he mentored young people from the APY Lands, alongside former Adelaide champion Andrew McLeod, and has now signed up as an ambassador with the Australian Childhood Foundation, an organisation that combats violence against women and children.

By some statistics an Indigenous woman living in remote or regional Australia is 45 times more likely to be the victim of domestic violence than a white woman. An Indigenous child is seven times more likely to be the victim of substantiated abuse than a white child.

Betts understands the issues because he has seen them. He has seen the violence and how normalised it has become in some communities.

“I’d see girls hit boys then they have a full-on fight,” he remembers. “I just thought that was normal. Until I was about 21, to be honest, then I knew it was not normal to hit a girl.”

It’s an astounding admission, but it also points to the depth of the problem.

Part of Betts’ role with the Australian Childhood Foundation will be to prepare its workers to know what to expect when they enter remote areas. “Because they are going to go there and get a shock right away,” he says.

The key, to his way of thinking, lies in education.

Betts never took school too seriously, skipping it all too often. When he arrived at Carlton in 2005 he couldn’t read or write and took three years of literacy and numeracy classes to catch up.

It’s also part of the yarn he tells when he travels to Indigenous communities.

“I tell my story to troubled youth, that there is light at the end of the tunnel if you change your ways, if you are committed and you want to put your mind to something that you want to do,” he says.

“I tell them the first thing you have to do is go to school and get an education.”

Betts is naturally proud of his culture and heritage. He is part of the Wirrungu people of the state’s west coast. The Wirrungu are based around Ceduna and Elliston but many over the years, such as the Betts family, have moved to Port Lincoln.

The Indigenous jumper worn by Betts and his team mates has been created by his auntie, Susan Betts. Betts is a renowned artist with her own company Wiyana Spirit and also designed Nalanji Dreaming one of four Qantas aircraft that carried Indi Indigenous motifs in the early 2000s.

When her nephew asked her to design this year’s Indigenous jumper for the Crows she was thrilled and had an immediate idea about what she wanted to represent and say through a guernsey that will be seen by millions across the weekend of football.

Appropriately, the crow is an important spiritual symbol in Wirrungu culture. It is known as the garnga, the “medicine man”. A medicine man who is a traveller from the spiritual realm carrying the messages of the departed.

“When we see him culturally, he tells us, he gives us those messages, so we know it’s from someone who has passed over,” Susan Betts says. “It’s not just about sorrow. It’s about healing. He is bringing that healing to us culturally.

“It’s like the ancestors coming through to say hello and to continue on with life and to bring that on. It’s OK to continue. He is very, very important messenger in our culture.”

To see Betts and 21 other Crows players run out on the Adelaide Oval tonight will be a moving moment for the Betts family.

“It’s very, very overwhelming, but also very empowering,” she says. “It’s such a powerful thing to see Eddie wearing it, representing his family, his culture, where he comes from, his background, where we come from.”

The Sir Doug Nicholls Indigenous Round itself is a powerful message. It’s a celebration of Indigenous footballers past and present and Eddie Betts enjoys seeing what other teams come up with and what stories their designs about other Indigenous cultures around the country tell.

“The round is a very important round and not just for Indigenous people but non-Indigenous as well,” Betts says.

But at times it can also unwittingly highlight the divisions that still exist in Australian society. It was in last year’s Indigenous round that Sydney champion Adam Goodes performed a war dance towards opposition supporters after kicking a goal at the SCG.

Goodes’ response was an answer to the racially motivated booing that had followed him around the country in his last season as a footballer. It was a booing that only erupted after the Wallaroo-born Goodes was named as Australian of the Year in 2014 and used his new platform to speak up for Indigenous causes.

Betts found the treatment of his friend Goodes distressing.

“Goodesy is a person who stands up for what he believes in,” he says. “A real powerful, passionate person that believes in his culture and people don’t like that.

“People can’t stand that.

“He’s a fantastic player, two Brownlow medals, and the way that he finished his AFL career was terrible to see.”

Betts though says Goodes’ treatment will not stop him speaking about and standing up for his culture.

“I talk about my culture all the time. When I go to schools I talk about my culture, where I have come from and how I got to where I am now,” he says.

You don’t have to spend much time with Betts to see how popular he is.

At Adelaide Airport he is besieged by young girls and boys, all asking for a quick word and a photograph. He is obliging to all. Flashing that famous, infectious smile and making sure they have what they need.

It’s another quality he traces back to his mother’s influence.

“Mum always brought me up to be nice to people and have manners so I guess that’s a good trait to have,” he says.

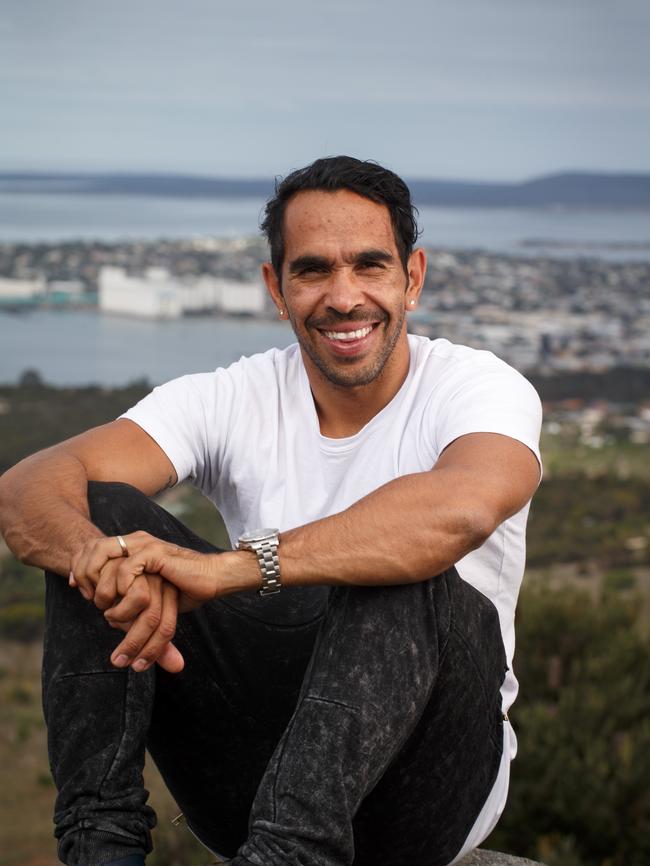

There is an approachability about Betts. In his black Cleveland Cavaliers cap, baggy white T-shirt and black pants he does look the part of an out-of-hours footballer, but carries it off without the ego. At 173cm he is not physically imposing, but there is a wiriness and a sense of the coiled-up tension of a spring that allows him to play footy in such a dynamic manner.

Betts puts down his evasive skills on the football field to his childhood spent in Boomerang Crescent, Kalgoorlie, where he lived with “my auntie, mum’s sister, my mum, mum’s brother, mum’s mum and dad all living in a three-bedroom house with 18 kids”.

“Just playing chasey with my older cousins and trying not to let them catch me,” he says with a laugh when asked how he developed those evasive skills. “Because when they catch you, they kind of bash you, so you try not to let them get you.”

Betts is 30 in November. An age when football players take stock and imagine what the next phase of their life may look like. Betts married long-time partner Anna last year and they have two young boys, Lewis and Billy.

His contract expires at the end of the 2017 season, but he is keen to keep playing beyond that. He says playing for Adelaide, the team he supported as a boy, has revitalised him.

“This is the best footy I have ever played these last three years,” he says.

“I think moving from Carlton to Adelaide really changed my career.”

Over 184 games at Carlton, Betts didn’t experience much team success. He arrived at Carlton in 2005, a time when the famous club was on a downhill slide. In his time with the Blues, there was little finals success and two wooden spoons.

“You can be in the system that long and not play in a grand final, that is how footy goes,” he says. “(But) that’s what you strive for, that’s what I want to achieve in my AFL career.”

Betts also wants to reach the 300 game milestone, a feat few AFL footballers achieve. Today’s game is his 239th, meaning by the end of next season, injuries permitting, he will be sitting at around 275-280, putting 300 tantalisingly close.

To hear Adelaide fans chant “Eddie, Eddie” whenever Betts is close to the ball and to watch them rise in anticipation when he looks like pulling another ridiculous goal from his bag of tricks leaves no doubt they would love him to stay as long as possible.

Betts has been surprised by how well he has been welcomed by the Adelaide faithful since his switch from Carlton.

“I was a bit worried about how I was going to fit in with Adelaide and how the supporters would embrace me, and from the word go they embraced me,” he says.

“I guess when you are having a bad day and you get a few kicks and you can hear them chanting your name it brings you up a little bit and gets your confidence going.”

Betts is hopeful he can play another three or four years, but is not convinced he will stay in footy once his career is over. He rules out a switch to the media, not wanting to be someone who pontificates on people he used to play with and against, and is unconvinced about coaching. What he wants to do is help in Indigenous communities.

“I like working in communities, trying to stop violence against women and children,” he says. “We will see how far I go with that and that may be my career after footy.”

But first, tonight at the Adelaide Oval, Betts will no doubt take centre stage once again. This time in an Indigenous jumper designed by his aunt Susan. The stage is set for another Betts Goal of the Year contender. ●

Adelaide v GWS, 7.10pm, Adelaide Oval