Don Farrell: Humiliation is not too strong a word for what happened

Don Farrell was finished – he’d left politics and even started a winery. It was, by his own reckoning, a crushing blow. Then the unthinkable happened, and now he’s back stronger than ever.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There’s a smile on Don Farrell’s face as he examines the news report on the table in front of him. It’s from February 2014, was published in The Advertiser, and possibly even written by the person showing Senator Farrell this particular story.

The first line reads: “It’s the end of an era in South Australian politics. To be specific it is the end of the Farrell era.’’

Yet, here we are eight years later and here is Farrell, more powerful, more influential than he has ever been.

He is the federal Trade and Tourism Minister and the Special Minister of State. He is also Labor’s deputy Senate leader, with another South Australian, Penny Wong, the leader.

It’s been a remarkable comeback for the 68 year old.

A new chapter in what had already been a prolific political life.

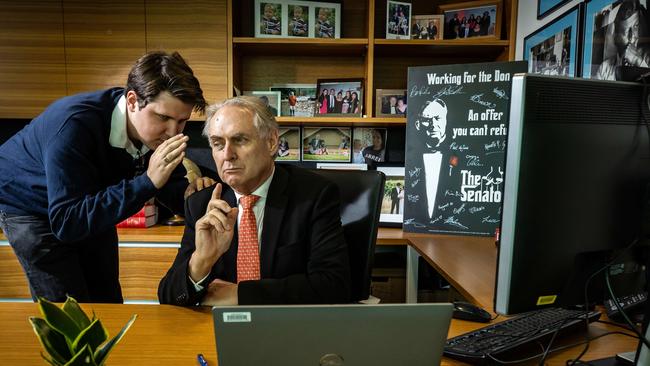

Hence the smile of the man who has long been labelled the “Godfather” of the South Australian Labor Party. It’s a tag Farrell likes to play up to.

“People often make the remark that the sequel in the case of the Godfather was better than the original, so I’ll perhaps hang my hat on that,” he says.

In my own defence, the consensus view back in 2014 was that Farrellwas finished as a serious politician. The previous year, he had lost his spot in the Senate.

After much public criticism, Farrell volunteered to step down from the No. 1 spot on Labor’s Senate ticket for the 2013 federal election in favour of the then finance minister Penny Wong. He had been on the top spot when first elected in 2007, but bowed to the public and political pressure.

At the time, the No. 2 spot was thought to be equally safe, but Farrell was swept away by a Nick Xenophon wave and he was out.

The following year, Farrell announced he would stand in the state election for the seat of Napier. The unforeseen element was the reaction of then premier Jay Weatherill, who threatened to resign if Farrell was preselected for the northern suburbs electorate.

Weatherill clearly believed political mileage could be made from being perceived to stand up to Farrell, with his long history in running the state’s largest union (the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees Association) and his associating with the turmoil at federal level that saw Julia Gillard replace Kevin Rudd as prime minister in 2010. Perhaps, Weatherill even saw Farrell as a potential leadership rival.

A shocked Farrell decided not to pursue the nomination. And that was supposed to have been that. Even Farrell thought his public life was finished.

“I mean, I understood politics very well, I understood how factional politics work and how political politics work. And I did think that there would not have been an opportunity for me to return,” he says.

His demise was a very public take-down of a man who had played a central role in rebuilding South Australian Labor politics after the shame of overseeing the collapse of the State Bank in the 1990s.

A man who played a pivotal role in advancing the careers of now Premier Peter Malinauskas, state Treasurer Stephen Mullighan and Infrastructure Minister Tom Koutsantonis.

The rejection stung. Not just for himself, but wife Nimfa and daughters Mary, Tess and Emily.

“Humiliation is not too strong a word I think for what happened,” Farrell says eight years down the track.

“When you have to withdraw in front of all the cameras, it was a very embarrassing period in my life and obviously for the family and for my wife. My children watched that all happen to their father.’’

So that was it. Farrell retreated from public life. He started a winery, Farrell Wines, in the Clare Valley, which became a form of therapy.

“My doctor says it’s very therapeutic for all my various ailments,” he says.

He set up a consultancy business with former state transport minister, and supposed factional enemy, Patrick Conlon.

His political career was saved by, of all people, Liberal prime minister Malcolm Turnbull.

A federal election was scheduled for 2016 and Labor had already completed its preselections for the Senate. But then Turnbull decided to call a double dissolution election, meaning all Senate seats were now up for grabs, instead of just half.

It meant Labor had the chance to have more senators elected from South Australia than it did in 2013.

At the time Malinauskas, a recently installed member of parliament, asked Farrell to think about running again. Farrell didn’t have to think too long about it. He was back in and is ever thankful to Turnbull, even comparing him to the famous deal where TV billionaire Kerry Packer sold the Nine network to disgraced entrepreneur Alan Bond for $1bn, then reportedly bought it for a quarter of the price.

“So just like Kerry Packer used to say, he only ever had one Alan Bond in this lifetime,” Farrell says.

“I’ve had one Malcolm Turnbull in my lifetime, and that resulted in me coming back into parliament.”

Farrell loves his winery, loves living in Clare, but politics and the Labor movement have always been his driving force.

Farrell grew up in Daw Park, where he went to St Therese School before graduating to Blackfriars Priory School.

He studied law at Adelaide University, but the original plan did not involve politics.

After finishing his degree, he planned to head to London to do his articles, but never quite made it. His cheap airfare took him through Dili and the Indonesians had just invaded.

Then, in 1976, he was offered a six-month job at the shop assistants’ union, the SDA.

The six-month job turned into a career and by 1980 he had run for and won the position as assistant secretary.

From there he built up a power base that was unrivalled in SA Labor. He developed the right wing Labor Unity faction into the party’s dominant grouping and, because of his strong instinct for the pragmatic, made peace with the left of the party.

Farrell is a factional warrior, but he is one who is more interested in winning elections than internal battles.

“Well, in order to govern in Australia, you’ve got to get 50 per cent plus one of the vote,” is his simple enough philosophy.

After the party’s electoral humiliation in 1993, Labor was left with only 10 seats to the Liberals 37. Labor knew it was a long road back to not only government, but any sort of credibility with voters.

Farrell knew the appearance of stability at the top was vital to that process and was instrumental in guaranteeing the unaligned new leader Mike Rann at least two terms to rebuild the party.

It worked.

Rann became premier in 2002.

His one-time business partner, and former Labor left powerbroker, Patrick Conlon calls Farrell “compulsively generous’’ and “loyal to a fault’’. He says Farrell and left counterpart, and now federal Health Minister, Mark Butler worked together to stitch back the party.

“The thing with Don is that he puts a premium on keeping his word, so it’s very easy to deal with someone who does what they say they are going to do,” Conlon says.

Conlon also believes Farrell has been mischaracterised and underestimated over the years as that right-wing bovver boy who steamrolls anyone who gets in his way.

“He’s very tolerant, he’s very encouraging of everyone,” he says.

“It’s almost like he’s got to be loyal to his faction, his church and all that, but at a personal level he is a very fair man.”

In person, Farrell is a quiet and unassuming figure. Unfailingly polite, he more resembles an accountant or a small practice GP than a high-powered political operator. One of his political maxims is “civility is not a weakness in politics”.

Despite his career, Farrell wasn’t born into the Labor Party. The most significant influence on the young Don came from his father Ted, who ran as an unsuccessful candidate for the Democratic Labor Party in the seat of Boothby five times between 1961 and 1972, then stood for the Senate in 1975.

The DLP split from the Labor Party because its members thought it too close to the Communist Party. It was a schism that helped keep Labor out of power for 23 years, until Gough Whitlam was elected in 1972.

As a child, Farrell would stand on polling booths handing out how-to-vote cards. His father would give his three children nightly lectures on the issues of the day.

“I’ve got a set of values which I guess my father inculcated in me,” he says.

“We used to sit around the kitchen table when we were kids. And he’d go through the political events of the day.”

Farrell says there has been a “constancy” to his views ever since. His critics paint him as a man out of his time.

A socially conservative Catholic, who is open in his continuing opposition to same sex marriage and abortion, Farrell believes his views have proven right many more times than they have been wrong over the years.

“I’m described as right wing, but in fact, I’m a centrist,” he says.

“By and large I am in the centre and I feel that I’ve got a pretty good feeling of what most Australians think about particular issues.”

But Farrell is not one of those politicians who bangs on about “silent majorities” or is arrogant enough to believe that his view is the only one.

He acknowledges that “a lot of the things I believe in are not the majority views in the community”.

Farrell is passionate about his right to express those views, but the pragmatist within him is also aware of the unmovable fact of those electoral mathematics of 50 plus one.

The necessary outcome of this is compromise, concession and negotiation; what Farrell calls a “coalition of like-minded people”.

“That doesn’t mean you agree on everything,” he says.

“But you agree on the fundamental principles that should govern an Australian government.

“What I believe in is fairness and a fair go and I find that people of the left support that proposition, even if they don’t support everything that I personally believe in.”

He values the role of the “conscience vote” within the party and insists he has never instructed any MP on how to vote on matters of conscience. Even if he tries to persuade them to his point of view.

“There’s no point saying to people, ‘Look, I want to exercise a conscience vote’, if you then say to other people, ‘By the way you can’t exercise your conscience’,” he says.

Farrell has friends on the left of the party because he is a relationship builder. Take the case of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

Back in 2013, then left faction leader Albanese was one of those calling for Farrell to step aside to allow the more high-profile Wong to claim the No. 1 spot on the Senate ticket.

Now Farrell is regarded as one of the PM’s inner circle, part of what is known as the Leaders Group. He carries the weight of the right faction with him but his brand of sensible advice is also valued.

“I think it’s a credit to (Albanese) that both of us have buried the hatchet and I’ve come to respect his judgment very, very much,” he says.

“Of all the sort of potential leaders, he’s actually the bloke that understands middle Australia better than any of them.

“I find nine times out of 10 we’re on the same page on an issue.”

Farrell was confident that Albanese would win this year’s election. In the same way he knew former leader Bill Shorten wouldn’t win in 2019 because he had dragged the party too far to the left of the political spectrum.

“The iron law of federal politics is that governments lose elections, oppositions don’t win. We turned that on its head in 2019,” he says.

Farrell has certainly been rewarded for his backing of Albanese. He has been given serious portfolios in trade and tourism. Trade, in particular, has its challenges, with supply chains choked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, soaring fuel and energy costs and the ongoing boycott of some Australian exports by China.

Unlike many winemakers, Farrell hasn’t been hit by China’s decision to impose tariffs of more than 200 per cent on the Australian product. Farrell Wines sells its 1000 cases a year in Australia, but he says the wine industry has been the “worst hit” of those targeted by China, followed by another SA staple in crayfish. The value of SA wine exports to China dropped to $9.4m in 2021-22 from $817m in September 2020 before the tariffs were introduced.

Farrell says trade diversification is key and is trying to conclude free trade agreements with the EU and the UK, and kick start the Indo Pacific Economic Forum.

Since taking office he has travelled to the US twice, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Germany, Switzerland and the United Arab Emirates. Part of the job, he says, is rebuilding Australia’s reputation on the world stage.

“When I first met the Europeans in Geneva in June, I think it’s fair to say that there was an audible sigh of relief that there had been a change of government in Australia,” he says.

The Europeans had been aggrieved by the decision of the Morrison government to scrap the $90bn submarine deal with French company Naval and by Australia’s tardy approach to climate change.

“Australia hadn’t changed just because the government has changed, but significant policy decisions that should have been made, that would have brought us into line, particularly with the Americans and the Europeans, marked us down in the rest of the world, climate change in particular,” he says.

Farrell says a free trade deal with the EU will open up a market of “450 million relatively well paid people”.

He enthuses about the prospect of Australia selling what are known as “critical minerals” to the EU and the US, including lithium, manganese and zirconium – elements critical for use in modern technology and to help build electric cars. The US has traditionally sourced much of these critical minerals from China, but is now looking to buy from other countries.

As for China, Farrell believes progress is being made, pointing to Albanese’s recent meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, the first time such a meeting had been held in six years, leading to hopes there will be a softening in the country’s trade stance and relaxation of the extreme tariffs that have hurt SA industry.

Even so, Farrell says Australia must broaden its trade interests. He says it’s not about turning the nation’s back on China, or even the US and the UK.

“But we ignored Asia for too long and we now have to refocus on Asia because, at the end of the day, India, Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia, all have massive populations, rising living standards, particularly in the middle class, and therefore rising demand for Australian products,” he says.

“The Morrison government was very Anglo focused. Anthony’s pushed us back into Asia.”

Indonesia, he says, presents a big opportunity.

“We simply don’t have a strong trading relationship with Indonesia, as we should. One of my intentions will be to try and build on that,” he says.

Farrell says the Labor cabinet has advantages that previous governments didn’t. One is that Foreign Minister Penny Wong was born in Malaysia, while another is that Farrell’s wife Nimfa is from the Philippines.

“So you’ve got a cabinet, probably for the first time, with not a majority, but a significant understanding of particularly Southeast Asia,” he says.

The Indo Pacific Economic Forum aims to encourage greater economic co-operation across 13 countries, including the US, Vietnam, New Zealand, Korea and Singapore. Farrell says the inclusion of the US is especially important.

“The Indo Pacific economic framework is bringing America back into the region for the first time since (former US president Donald) Trump,” he says.

Tourism is Farrell’s other post-pandemic responsibility and in October he was spruiking a $125m global advertising campaign featuring a kangaroo called Ruby and the tagline “Come and Say G’day”.

For a man who for some epitomised the term “faceless man”, and was painted as a Machiavellian backroom operator, Farrell is leading a high-profile life. But he says the “faceless man” jibes were always wrong anyway.

“Firstly, I do have a face and it may be a face only a mother could love but it is a face all the same,” he says.

“And the idea that I was an obscure political character, is not true.

“I was a very high profile South Australian person, I was the head of the shop assistants’ union, which was regularly in the media about shop trading hours.”

The faceless man motif was wheeled out again when he was one of the main instigators of the move to dump first-term PM Kevin Rudd in favour of Julia Gillard.

“Now, whatever you could say about my role in the demise of Kevin Rudd, I was a politician, I was elected, I was actually a vote in the caucus,” he says.

The Rudd-Gillard battle defined and destroyed successive Labor governments, ending when Rudd lost to Tony Abbott in 2013, condemning Farrell’s party to opposition for almost a decade.

Asked if he has any regrets in overthrowing Rudd, Farrell is adamant. “No, no, no, no, no.” He says he is proud of “my role in electing Australia’s first female prime minister”.

“I think she turned out to be a terrific prime minister,” he says.

“Circumstances meant that she only got one term, but I’ve never once had a moment’s regret about electing Julia Gillard and supporting her right to the bitter end.”

Much has changed since then. Governments have come and gone. The world has been through pandemic and war.

Farrell says the globe is more “unstable” than it has been at any time since the Cuban missile crisis in 1962.

Yet, there is a feeling that Farrell is as happy as he’s ever been.

He is actively relishing being in the middle of all this chaos.

Possibly because, to return to the world of film, as Liam Neeson says in the action flick Taken, Farrell also has a “particular set of skills, skills I have acquired over a very long career”.

Or as Farrell puts it in his typical more low-key fashion. “After 46 years of negotiating in Labor, politics and trade unions, I feel as if, you know, my time has come.”

The Advertiser will next week publish a list of South Australia’s 50 Most Influential People for 2022. Be sure to log on or pick up a copy to see if “The Godfather” makes the cut. ■