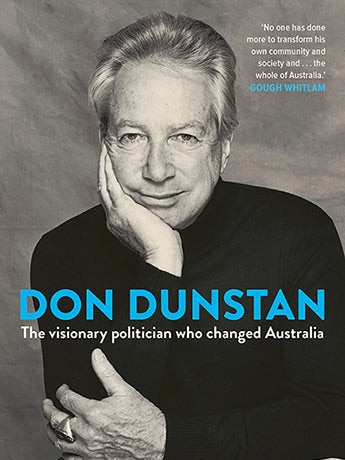

Don Dunstan: The man who could’ve been PM

It has been 20 years since the beloved Don Dunstan died — and two decades after his death, the first full biography documenting his life comes to a stunning conclusion.

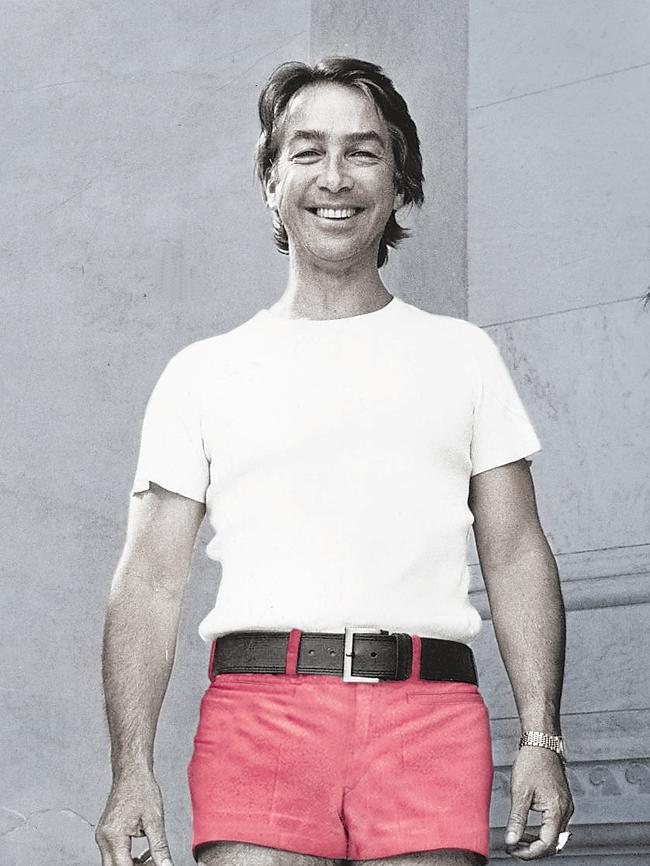

At a gay pride parade in Adelaide in 2015 celebrating 40 years since the decriminalisation of homosexuality, one group calling themselves the Marching Dunstans wore dusty rose pink shorts and white muscle T-shirts.

Dunstan probably would not have minded but he never saw himself as a gay icon.

“He referred to himself as bisexual,” says historian Angela Woollacott who has completed the first biography of Dunstan, 20 years after his death.

“He used the term ambisexual and he put the emphasis on freedom of sexual expression, not on being gay.”

Dunstan’s core belief was not so much gay rights as free love and it was one of his unshakeable faiths like civil liberties and social democracy that he came to when he was young, and held for life.

His sexuality, always intriguing, was in one sense private but as Woollacott’s biography shows, it was part of the story that defined him, including by restricting his ambition to South Australian politics when he had the skills and charisma to lead the nation.

“Absolutely he was of the calibre of Hawke and Whitlam. In fact, some people think that he had abilities that Whitlam didn’t have in terms of being more of a consensus person,” says Woollacott who is the Manning Clark Professor of History at ANU.

“I think he was one of the great leaders.”

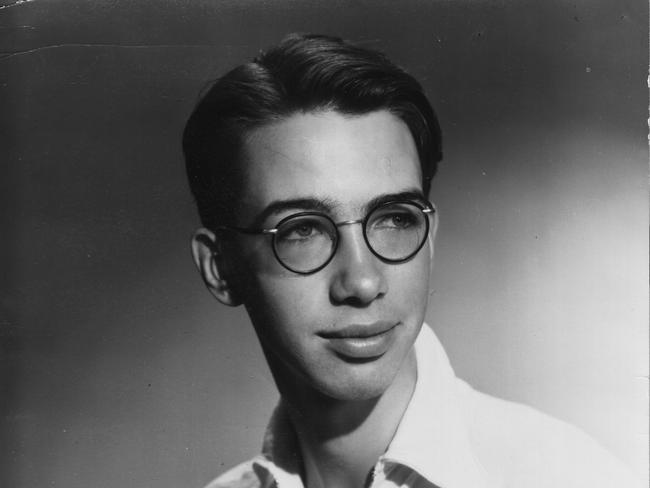

The gifts that served him so well, included debating and acting, came naturally to him and were developed at school at St Peter’s College.

He looked good and performed well on television at a time when many of his colleagues were stilted and wooden.

Importantly, he had an ability to present reformist ideas in an unthreatening way by making concise and compelling arguments. He could propose a radical shift and make it sound like the voice of common sense.

“He had an ability despite his extremely well-educated accent to relate to ordinary people,” Woollacott says.

“I think it was partly his passion. He always came across as someone who believed what he said, and I think that is a key thing.”

Eight years ago Woollacott was looking around for a biography subject when she attended a conference in Adelaide and heard the Dunstan Foundation, which honours Dunstan’s legacy by promoting reformist ideas, had put out feelers.

It was already a long time coming given the former South Australian Premier died in 1999 and before that conducted a series of interviews with Melbourne academic Allan Patience with a biography in mind.

Patience worked on the project for a number of years but in the end decided not to proceed.

He then put his research material into the Dunstan Collection at Flinders University, which had been founded on an extensive collection of papers, speeches, photographs and other material that Dunstan donated for scholarly use.

“I thought, ‘that’s the biography I’d like to do, what an important story’,” says Woollacott. “I knew it was a big one.”

She went through the Dunstan Foundation’s process of receiving permission to do the work from Dunstan’s three children, one of whom, Andrew, she had been an undergraduate with at ANU.

She Skyped him in North Carolina where he lives and all three agreed, including Bronwen Dohnt, a former teacher at Annesley College, who shared memories and material.

Others had sampled Dunstan’s life before.

In 2014, Dino Hodge, a historian who grew up in Adelaide, published Don Dunstan Intimacy & Liberty, which focused on the former Premier’s sexuality and commitment to the rights of homosexuals.

And in 2013, Flinders University academic Ruth Starke published Media Don, an extended essay that was intended then as a chapter of a planned book on Dunstan.

It took a detailed look at his astute understanding of the way the media could be manipulated for political advantage.

Starke detailed the day in 1972 when Dunstan ducked away from his own press advisers to offer himself up to photographers on the steps of Parliament House wearing the shorts.

It caused such a stir, Woollacott thinks, because of the combination of the tight shorts with a fitted white T-shirt.

It was a highly inappropriate outfit for the floor of state parliament but, she thinks, Dunstan wore it partly because of vanity; he had been working out and looked fit.

“He had a kind of daredevil streak to him and I think that came out that day,” she says. “It was a combination of cheeky and vain.”

Woollacott devotes much of her book to Dunstan’s early life in Fiji, and his marriage to Gretel.

They were radical social thinkers who believed in an open marriage and read works by Bertrand Russell and others that were favoured by European intellectuals like Simone de Beauvoir and her lover Jean-Paul Sartre.

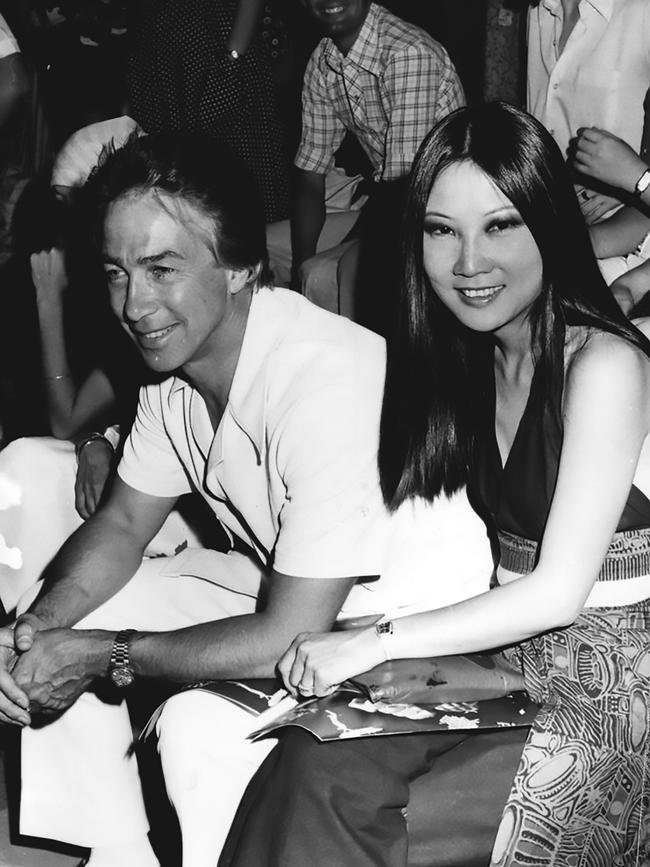

Funnily enough, it was Dunstan who struggled with jealousy more than Gretel appeared to in his first marriage and again, later, with his second wife, Adele Koh.

The book follows his ascent to power and the way his ideas were formed.

He early on established himself as a Social Democrat who rejected Communism because he had read Marx and Engels and thought it was “fantastic nonsense”.

In June, 1967, aged 40, Dunstan became Premier, although it was short-lived.

At an election the following year, he lost to Steele Hall — they were both handsome men and the campaign became known as the battle of the matinee idols — even though he won 53.2 per cent of the vote.

But Hall, true to his word, partially abolished the gerrymander that propped up the Liberals and lost to Dunstan in 1970.

It was the start of the Dunstan decade.

He became the most successful politician of his generation and his popularity polls were the envy of premiers everywhere; even when his polls were low he beat the others.

South Australians loved him because he energised the state, introducing important social reforms and freedoms while encouraging a serious food and wine culture that gave South Australia a distinct new personality.

But Dunstan had his personal weaknesses and if the press had ever pursued them, his premiership would have been derailed.

For reasons that were never really discussed, South Australia indulged Dunstan and engaged in a kind of tacit deal that judged the benefits of Dunstanism were worth it.

His problem lay in the way he showed excessive loyalty to the wrong people and Woollacott thinks this relates to his childhood.

In Fiji he was a sickly boy and when he turned seven his mother left him in Murray Bridge where he lived with his aunt and grandmother until he was 10.

“He was lonely, he didn’t have a lot of friends. I think it was a desperately lonely period of his life and he missed his mother in particular,” Woollacott says.

“I think that period made him crave for affection.”

The pattern of risky behaviour began with Gerry Crease, a media adviser who was gay and became so close to him that when Dunstan and Gretel were planning a holiday house, he was included in it.

There were rumours about his odd behaviour and suspicions that he and Dunstan were lovers.

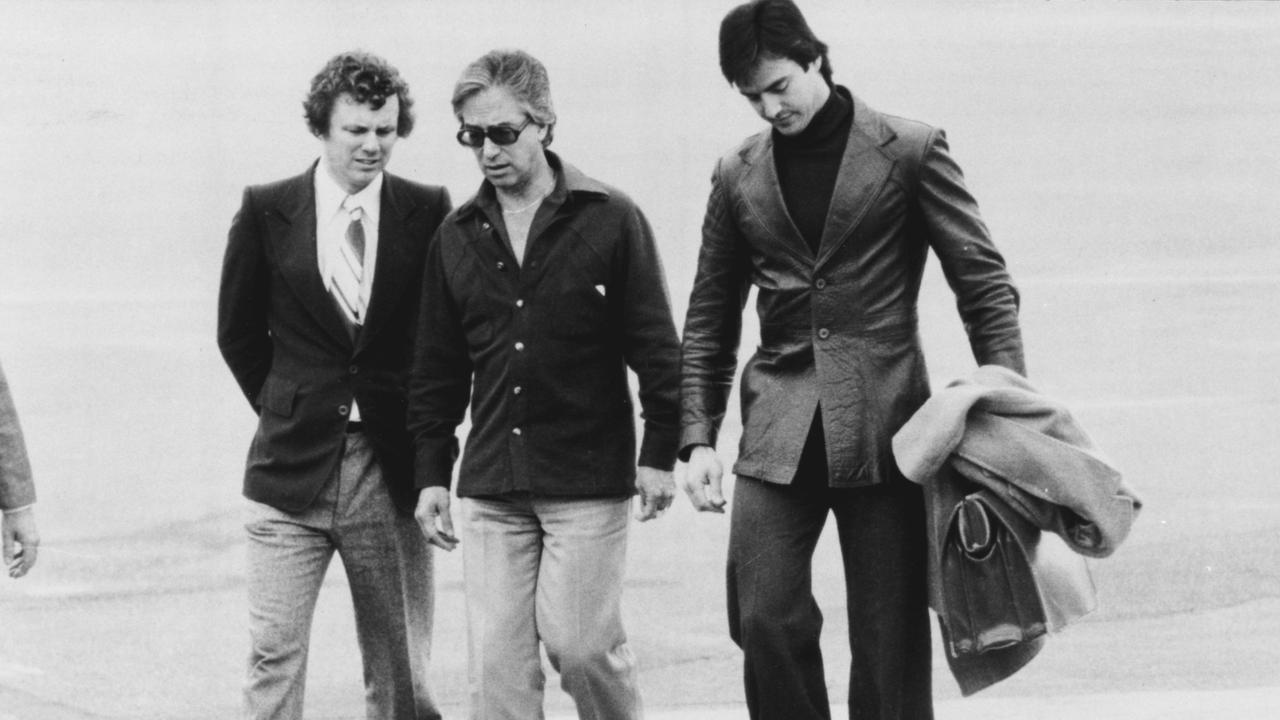

In early 1969 Crease died of a drug overdose and both Dunstan and Gretel were devastated. Then along came John Ceruto who Gretel didn’t like and who Bronwen and her brothers thought was “a sleaze”.

But Dunstan was infatuated and in 1971 he put Ceruto on staff to work on arts and tourism as a catering officer.

Woollacott quotes former journalist and media adviser Peter Ward, who fell out with Dunstan over Ceruto, in a letter in which he called Ceruto “a dumb, strutting, over-muscled male blond, practically illiterate and without social skills”.

He also, apparently, reeked of Brut.

Ward wrote to Dunstan warning him in the strongest terms that he and John were “good copy” for any newspaper that went looking, particularly as Dunstan and Gretel had separated. Dunstan did not take the advice and his relationship with Ward was badly damaged.

There was almost certainly an affair — Ceruto who was later a heroin addict released private letters — and Dunstan had clearly abused his power by appointing Ceruto to his staff.

Woollacott defends him, saying it was a mistake but not a big one.

“If you want to put it anywhere near the category of corruption, I think it’s pretty small,” she says.

“It was a mistake but I think in the scheme of things I wouldn’t rate it as a particularly serious abuse of public office.”

He got away with it and the Adelaide press went a step further and protected his privacy when his second wife, Adele Koh, was dying of cancer.

All of the South Australian media agreed not to publish stories about her illness, which had been diagnosed in March 1978 after a miscarriage the previous year.

This respectful silence was broken by radio broadcaster Derryn Hinch who asserted his right to inform his Melbourne listeners and Dunstan never forgave him.

Adele died in October 1978, aged 36.

After her death, Dunstan destroyed the diary she had asked to be held in trust by the State Library and kept sealed for 50 years.

Woollacott says this was again the result of Dunstan’s personal conflict between his belief in their open marriage and the reality of reading about Adele’s lovers.

“For him, the pain of reading detail, when she named names in the diary, was too painful for him and he didn’t want others to know it,” she says.

Adelaide loved and forgave him but would Canberra? Dunstan thought not.

The illegality of his homosexual affairs before decriminalisation and the continuing lack of social acceptance of gay men through the 1970s — at the first mardi gras parade in 1978, police bashed gay people because they thought they could get away with it — made shifting to Canberra problematic.

And his coiffured hair, jewellery, theatricality and close attention to what he wore meant he looked gay before any concept of metrosexuality had entered the culture.

Whitlam repeatedly urged Dunstan not to waste his time in South Australia and move into federal politics and Dunstan considered it, according to Woollacott, telling his then lover Judith Pugh that he and Hawke had an agreement in which one would be Prime Minister, the other Treasurer.

Ultimately, he did not risk it.

“By the mid-1970s he knew that the Canberra press gallery was a pretty serious operation and that people would have investigated him and he would have been subject to all kinds of hounding on that issue,” she says.

“It had been an issue for him since 1967 when On Dit published a story about him and Gerry Crease. He knew that stories about him and his sexual relations were dynamite, and that they could really damage him.”

Don Dunstan by Angela Woollacott will be on sale Monday (Allen and Unwin, RRP $32.99)