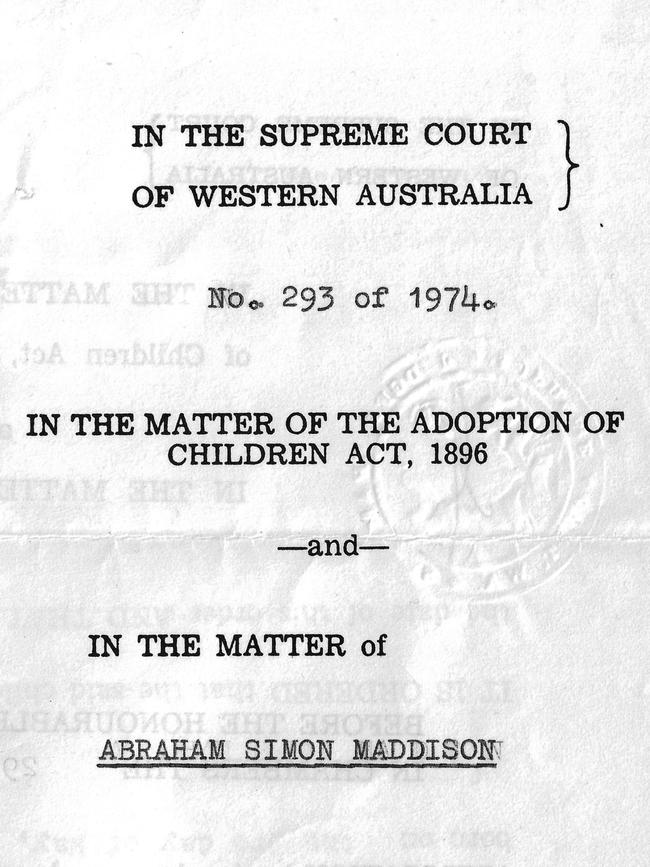

Crazy Bastard: Extract of Abraham Maddison’s book about a tumultuous journey through forced adoption

Adoptee Derek Pedley always believed he was abandoned. But a letter from his mother revealed an astonishing truth – the story of Abe Maddison. Read his book extract.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“Hello, is that Derek?” It’s an older woman’s voice, hesitant.

“Yes?”

I’m impatient and running late, pausing between shirt changes to answer the call. I’m in a department store change room at Tea Tree Plaza, in the northeastern suburbs of the southern Australian city of Adelaide. I have a speaking engagement at a suburban library tonight and I’m trying to find an outfit that looks a bit “writerly”.

After a brief silence, she says uncertainly: “You don’t know me but … I have to tell you … Joye’s dead.”

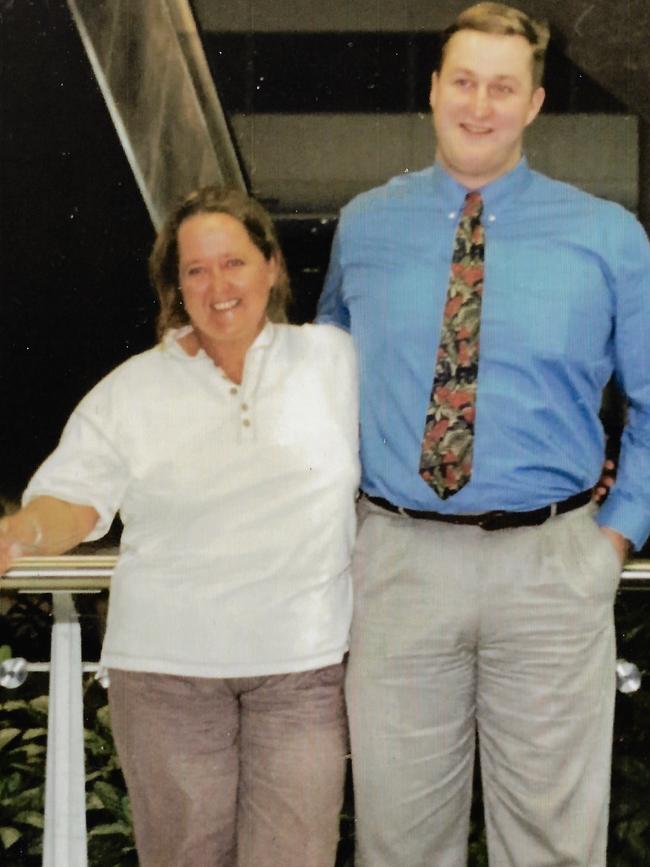

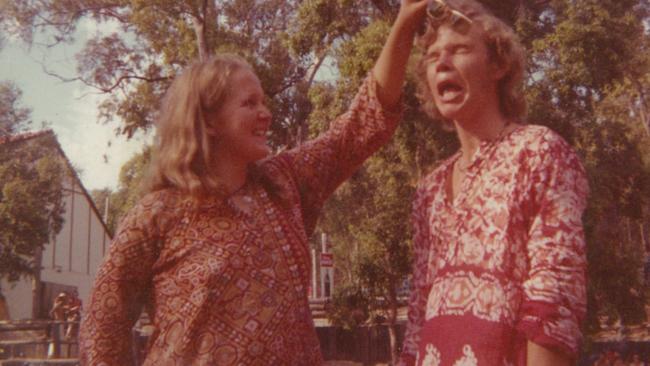

Joye Maddison is my mother. She gave me up for adoption in 1972. I found her in 1994, we reunited in 1995, and she rejected me again in 2004. If anyone asks – and sometimes they do, because everyone’s curious about “what it feels like” to be adopted – this is the very concise narrative they receive, and it does not invite further questioning.

Now, nine years later, she’s dead. Dead.

My breathing becomes laboured and the tunnel vision of an anxiety attack closes in. My heart pounds through my ears and I struggle to form words for a reply. It is June 2013. I’m 41 years old.

I will eventually learn that, months earlier, Joye had been diagnosed first with emphysema, then lung cancer. She had sworn the family to secrecy; I was not to be told. They reluctantly agreed. Until this phone call from a stranger about her death, I’ve kept Joye out of my thoughts. I didn’t even know where she was living, or where she was when she died. I assumed she was still in Kakadu National Park, in the Northern Territory, where she was living and working at the South Alligator Ranger Station when I reunited with her in 1995. But when I take the call, I am oblivious to the seismic shifts in her life since she abandoned me again.

“Abandoned”. That’s the label on the vault in my head where I keep my adoption safely locked away. I refuse all pleas from our family and her best friend to travel to the Territory for her funeral, in some remote place called Daly River. I discover she’d been there for years, working in landcare. When we reunited, she’d been obsessed with eradicating a weed called mimosa pigra, which was a threat to Kakadu’s ancient landscape – still mostly pristine, but fragile and threatened.

This is an extract of the book Crazy Bastard – A Memoir Of Forced Adoption, by Abraham Maddison (Derek Pedley), Wakefield Press, $39.99

In a subsequent phone call, Faye – Joye’s best friend and the stranger’s voice that broke the news of her death – tells me the Daly River locals thought so much of Joye that they’ve sought special permission to have her buried in the local cemetery. She will be the only whitefella laid to rest there.

It’s a rare and enormous honour. I really should come, Faye pleads gently.

NO. I am completely overwhelmed by all of this and refuse to process any of it. There will be no second reunion, no forgiveness or understanding or reconciliation. It is done, over. My heart hardens in an instant. Joye abandoned me at birth; she abandoned me in life, after our reunion; and now she has abandoned me in death. I retreat to the mantra that’s served me since the day I stumbled on my adoption papers at 15.

Everything’s normal. I’m fine. I’m Derek.

Faye, who is also Joye’s executor, messages me a month later. I wanted to let you know that I found a letter/diary to you soon after your birth – I wonder if you would like me to send it to you now – or hold off until you are in a better frame of mind.

I reply: Please do send me the letter, I would very much like to read it, thanks.

But the only thing she sends me is a disposable plastic bag bulging with Bob Dylan cassettes. I don’t like Dylan, or his annoying, nasally whine, and Joye knew that. Faye doesn’t, but it still makes me angry. I am easily angered. My life is a deeply unhappy place.

After she returns home to Alice Springs, Faye is difficult to contact. She is an artist and is married to a man named Huckle, another friend of Joye’s from the 1970s. I know little else about them, other than they both travel a lot. Our communication is prickly because of my anger, and I struggle to forgive Faye for telling me, “Joye’s dead”. I can’t get the phrase out of my head.

I don’t pursue her over the letter. What difference could it make? I’ve shut the door on this. A few words that Joye wrote in 1972 won’t change the past. Joye, and adoption, have brought me only pain. I put it back in the vault and move on with my unhappy life.

I have no accurate count of the number of times I self-harmed or attempted suicide in my 20s, but it was a lot. I am clueless with women and it goes back a long, long way – to an ill-fated teenage crush.

But I have no interest in seeking the truth of that shameful obsessive behaviour. For decades, I’ve told myself this: I am an incorrigible romantic in search of a fairytale.

And this time, I tell myself, I’ve found it. I’m months into a whirlwind Tinder romance, convinced that this time will be different. Shannon has changed my life. She is incredibly smart, poised, witty and sexy. I have no clue how or why she is with me. I am deliriously intoxicated by her.

We gush over each other on Facebook. And I sense side-eye among our friends and families over the swiftness with which we’re moving forward.

I really don’t care. Shan is my redemption arc, the deus ex machina in the s**tful story of my life. But in the back of my mind is the unsettling knowledge that it’s not the first time I’ve thought this of a woman. And if I know anything about myself, it’s this: if there is a way to f**k this up, I’ll find it.

Two months after Faye’s email, there’s no sign from her of the letter from Joye and no word on the adoption documents I’ve requested from WA authorities to help Faye sort out the will, and to potentially give me more answers than the two-paragraph origin narrative I was given back in 1994.

I’m frustrated and have stopped anticipating mail deliveries. But one day, when I rush out the door late for work, I flick up the lid on the letterbox and there’s an A4 Express Post envelope from Alice Springs.

I ring Shannon. She pleads with me not to read it until I get home from work, but I can’t wait another nine hours. I’ve waited 46 goddamn years for these words from my mother. I rush into the city and when I sit at my desk in The Advertiser newsroom, I ignore the story queue on my screen and begin reading Joye’s shaky scrawl.

Every couple of hundred words, I quickly slip away to the men’s toilets to sob quietly in a stall. Then I compose myself and repeat the cycle. By the time I reach the end of the letter, the story queue has grown and the boss is giving me glances. I put aside the letter and dive into the news of the day, glad of the distraction from this emotional whiplash.

At home that night, I stand in my kitchen and carefully unfold the pages again, taking deep breaths as I prepare to read these words out loud.

Shannon wraps her arms around me. Over the next few minutes, she holds me up as I squint and stumble my way through it again, voice cracking. Later, my CEO-historian girlfriend will properly study each of these 2700 shaky words. She emails them to me with the subject line:

Your first love letter, from the woman who loved you first, transcribed by the woman who will love you last.

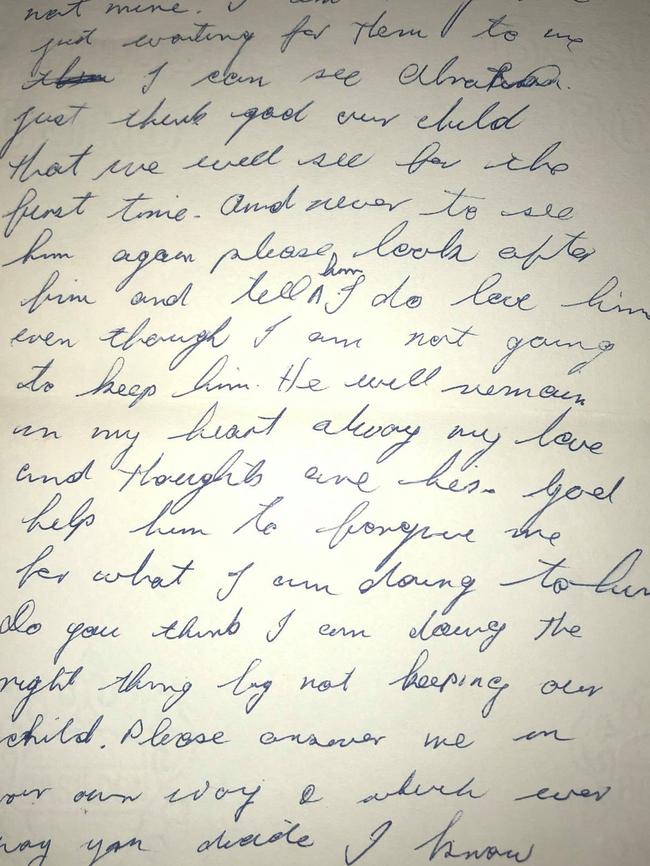

The letter opens: How do I begin to describe or even explain what has happened over the last nine months?

Some of the words are almost too hard for me to speak. It quickly becomes a struggle to get through each sentence.

Well, my dear son Abraham Simon, I have finally seen you. You didn’t even cry or open your eyes. Didn’t you want to see your Mum. Yes, Abraham, I am your Mum and I love you deeply please don’t forget me, for I will never ever forget you or your sweet peaceful loving face.

Abraham, I feel so very close to you at this moment my heart is full of love and also of so much sadness. Yes, there is a song on the radio at the moment. (The) First Time Ever I Saw Your Face. Yes, I will never forget your gently serene face. What more can I say my son? Only that I love you so much it hurts and fills me with sadness … please don’t forget the feel of your mother’s arms as I am terribly sorry and sad that it will be the only cuddle or feel that I will give to you.

In my mind’s eye, I see 18-year-old Joye alone, in hospital, listening to Roberta Flack and writing this heart-wrenching letter, after they’ve taken me away. After she has held me in her arms for the first and last time.

Every word is imbued with the raw intensity of her pain. It scalds me. All my defences and denial crumble.

I knew nothing. Nothing. How dare I treat her the way I did?

How f**king dare I?

Days later, YouTube gives me the soundtrack to the scene Joye describes.

Roberta Flack sits at a piano, singing live. I sit silently, swallowing sobs as her voice and words almost break me. They almost, almost break me.

By Page 20 of the letter, I am gone from Joye’s life.

Hi Abraham, well my son, you are really gone now. Yes, yesterday was the final day for me, and I thought it was Friday and I suddenly realised that 11/6/1972 was Sunday. I really don’t know how to say sorry to you for I am sure now that I made a mistake. I shall never forgive myself for what I have done. Please forgive me, and I shall keep searching for you until I find (you), and I only hope that one day we shall meet.

I wasn’t ready for any of this. Great, heaving sobs wrack my body when I reach the end of the letter. Shannon hugs me tightly. My adoption was not voluntary. Joye had not thrust me into the arms of the authorities.

She was given no options that allowed her to keep me. Instead, she was pushed out the door and told to get on with her life. I was not abandoned.

I write back to Faye a few weeks later, in April 2018.

The letter was the most difficult thing I’ve read in my life. I read it, out loud, once, and haven’t been able to read it again yet. It just broke me in a way I can’t even begin to explain. Yet somehow it has also brought me a deep sense of healing. I understand now. I finally understand what she went through. I wish I was able to see her one more time to tell her it’s OK, that I love her and thank her for loving me so much that she gave me up.

It’s not to be, though – I am so sad I never had the chance to say goodbye, and also that I had to wait almost 46 years to receive that letter. But I’m also just simply grateful I now have it and will treasure it.

Is there anything else you can tell me about the letter? Did you find it, or did she tell you about it? In her last days, what do you remember her saying about me. I’d like to know more, please.

But Faye can offer me little. Joye’s health declined quickly while Faye cared for her at Joye’s home – a place called The Five Mile, at Daly River.

The single conversation they had about me in those last days was never completed.

Reading Joye’s letter is the catalyst for some sort of awakening: one that will rapidly accelerate in the weeks and months ahead, as I make further stunning discoveries about my life and my mother’s. This adoptee’s not buying bulls**t narratives anymore. I am desperately sad for my mother, and f**king angry at the system that did this to her.

I also know I’m not even close to being ready to face any of it, because I simply do not possess the strength or the resilience or the insight or the belief that requires.

And beyond that is the shameful truth that there are parts of myself – things I’ve done, behaviour I have engaged in – that I cannot bear to face.

I don’t have the time or the desire to confront any of it, anyway. And why should I? I have wonderful kids, a stable career and income, and an amazing new girlfriend. We’re going to live happily ever after and I’m good. Really, I’m fine. This stuff is all in the past. I don’t need to dig further. I got my fairytale – the one I’ve chased all my life. I can move on.

As we stand in my kitchen and I wipe tears from my eyes, shaking from the power of my mother’s words, Shannon sees only the serendipity of it all: an irresistible opportunity for this troubled man she’s fallen for.

A relationship was not on her radar. But here she is, standing with me in one of the most pivotal moments of my life.

She is yet to encounter my ability to self-sabotage and has not yet stumbled on the improvised explosive devices that I, like so many adoptees, scatter through the minefield of a relationship.

And she hasn’t yet recognised the truth that I’m also blind to: I am stuck in a loop, chasing a fairytale fantasy that never comes true.

Shannon grabs me by the shoulders, presses her forehead to mine. Her hazel eyes bore into mine, sparkling with a madcap idea.

“Dude,” she implores me. “When the universe gives you archival material and Tinder gives you a historian, what are you going to do? You are going to WRITE A BOOK!” ■