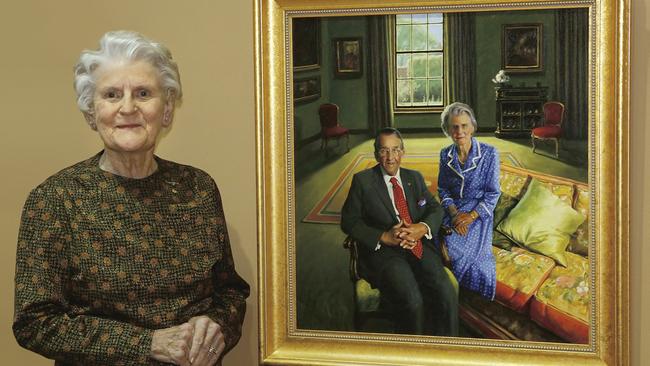

Couple James and Diana Ramsay make biggest donation in SA art history

The Art Gallery of South Australia is set to receive the biggest bequest in Australian history — but who were Adelaide couple James and Diana Ramsay? And what drove their desire to give?

- Magic childhood moment that inspired Diana Ramsay to donate

- Diana Ramsay gives $510,000 towards ASQ’s Guadagnini cello

It began with a fine Negoro red lacquer tray from Japan – a combination of simplicity, utility, elegance and rustic beauty – made around 1700. Diana and James Ramsay thought the piece so splendid they wanted others to enjoy it, so they gave it to the Art Gallery of South Australia.

That was in 1972.

It was the first step on a philanthropic path that would wind across almost half a century and eventually lead to the stunning decision, announced on Saturday, to provide what is believed to be Australia’s biggest cultural bequest, a $38 million gift designed to snowball even as it supercharges the gallery’s future with cash to transform its collection.

The bequest by James, an accountant who died in 1996, and Diana, who died in 2017, is structured to be a perpetual “magic pudding” for the gallery.

It protects the capital, which is to be invested, while allowing the gallery to spend a portion of the interest to buy great works of art.

The more it grows, the bigger the dividend for art – indefinitely.

No wonder the AGSA’s director Rhana Devenport is over the moon.

“It’s a tremendous, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the gallery and it registers a level of philanthropic faith and trust that’s really extraordinary in this country,” she says.

The Ramsays were enormously generous but private people, who, without children, found pleasure in giving.

They began with little money, but became wealthy when James, a Tasmanian, received part of the inheritance from the Ramsay family’s Kiwi Boot Polish fortune.

The company, started in Melbourne by James’s uncle William, was a major international success and was sold in 1984.

The couple’s dream was to follow the guide of pharmaceutical manufacturer and businessman Alfred Fenton, who wrote in his diary back in September 1903: “Wealth!! Get it spent”.

When he died four months later, he willed £383,163 to art and charity, with half of the interest earned to be used in perpetuity to buy works for the National Gallery of Victoria.

The Felton Bequest helped the NGV buy 15,000 works, which, in 2004, were valued at more than $1 billion, including by Rembrandt, Monet, van Gogh and Turner.

While the Ramsays used to say they couldn’t hope to match Felton, in fact the AGSA says their bequest is even bigger in current dollars – although art prices have also surged enormously in the past century.

Yet even if the Ramsay bequest cannot achieve the dizzy heights that Felton allowed the NGV to reach, it will help transform the gallery’s collection – almost entirely funded by private donations – for many decades to come.

James drew up the bequest plan in 1994, to take effect after the death of his wife. Ninety per cent of it is from his estate, and the rest from Diana’s.

However in the years since James’s death in 1996, Diana had continued the couple’s philanthropic bent.

In 2009, after new tax laws designed to encourage philanthropy, she launched the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation, which – as well as backing other arts groups such as the Australian Ballet, medical research and at-risk youth – has been a main supporter of the AGSA.

For example, the Camille Pissarro impressionist painting Prairie à Éragny, bought in 2014 for $4.6m, came with a hefty input from the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation.

The magical silver cigar sculpture on North Tce, immediately outside the gallery, The Life of Stars, is another one helped by their money.

Then there is the $100,000 Ramsay Art Prize, the nation’s richest contemporary art prize for artists under 40, held once every two years. And one of the most visited parts of the gallery, The Studio, designed specifically to foster art among children, was also funded by Diana.

The pair did not have much when they married. James, who served as a financial officer in the military in World War II, did come from a well-off family.

His father, Sir John, was a famous surgeon, while one uncle, William, founded Kiwi boot polish and another, Hugh, was a famous artist.

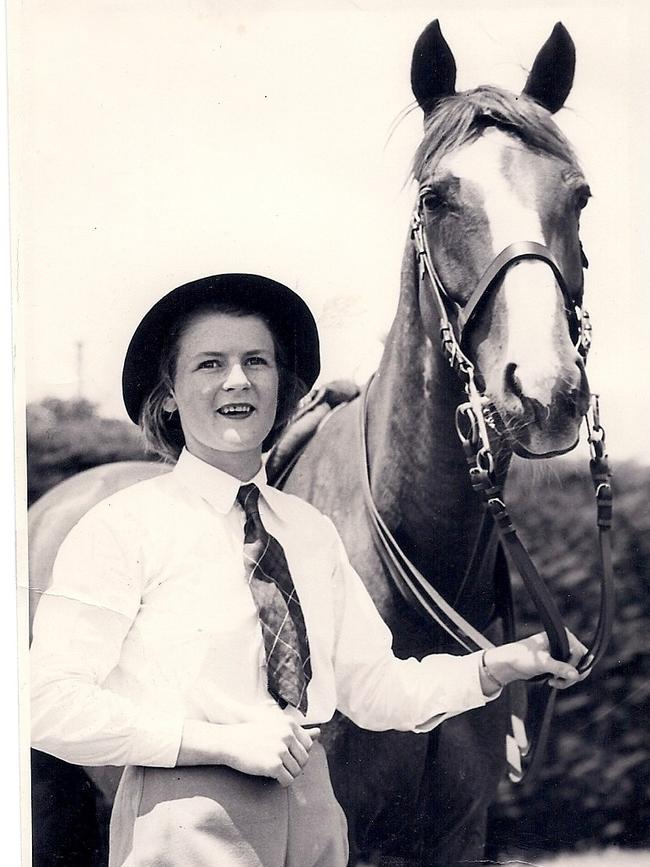

Diana, from the Hamilton winegrowing family in SA, said the pair fell quickly in love. “We instinctively knew that we were meant for one another; we married in 1960 and lived life to the full – on rather low means,” Diana said once. “We soon learnt to save money so we could redeploy some, purely to make more of it to help others.”

The Kiwi cash, well invested, meant there was more to give. “They certainly brought the words ‘joy of giving’ to life, and they so enjoyed giving it,” says Kerry de Lorme, a friend of Diana’s and executive director of the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation, which will continue its work.

A letter from James to the Australian Ballet back in 1994 makes the point: “As today is our wedding anniversary,” he wrote, “we can think of no better way to mark the occasion than to further give to the Australian Ballet Company of which we are so fond.” A cheque for $30,000 was enclosed.

Unlike some bequests, which require building work, this is purely for the collection of major works of art.

It also requires some of the interest to be set aside so that once a decade a “major, major” work can be acquired, says AGSA director Devenport.

“This is a gift for the people of South Australia and given we’re the most visited art museum per capita – last year we had over 1 million visitors out of Adelaide’s 1.3m – it’s already a collection of great maturity and excellence,” she says. “This allows us to take the collection to the next level.”

With 45,000 individual pieces of art, the AGSA has one of the biggest collections in the country, even if, with its comparatively small physical space, it struggles to find places to show them all, and store them.

It is also one of the most valuable assets South Australians own.

Devenport says the collection is valued at just under $1 billion, which represents 17 per cent of the state’s assets, or 61 per cent of its cultural assets.

Devenport has already made some new acquisitions from the bequest. Her first was The Black Watchful, a portrait by British-Ghanaian artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. The piece is raw and pensive, showing a black girl and small dog watching something out of the frame, against a background of dark greens and greys.

It hangs in contrast beside a Thomas Gainsborough portrait. A further work funded by the bequest, a sculpture by Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson exploring perception, will be unveiled next year.

“I thought a lot about what the first major acquisition should be, and I’d been looking at Lynette’s work for a couple of years,” says Devenport.

“There was a queue of 400 people for her work. So it takes some time. And this was a really major piece … and I thought it was a really poignant and powerful painting. I thought being a woman, and a woman of Ghanaian descent, it would make a really interesting interjection and conversation within the history of British painting.”

She says future purchases will cover all kinds of styles and periods.

“But of course, James and Diana loved historical art; it was Nora Heysen she fell in love with when she came to the gallery when 10 with her father,” Devenport says.

“The bequest will not only be used for contemporary art – it will absolutely encompass historical, modern, contemporary, and across all our collecting areas including Australian art, international art and Asian art as well.”

But is there room to show off all this new art?

While the gallery has in the past argued strongly for a second building for contemporary art, the Marshall Government has supported an Aboriginal art gallery.

Devenport says space remains an issue.

“What we would hope in the near future is support for an expansion for our display space and our public space,” she says.

“That’s obviously very evident as everyone has known for some years the need for the gallery to expand its footprint, to be able to show more of the collection, and also more public spaces.

“At the moment we don’t have an undercover or sheltered place to have our openings, which is a little bit of a problem, and also with commercial space … our hospitality is a huge part of how museums become more sustainable into the future. But more important is the collection.”

How the Ramsay Bequest allows that collection to change cannot be predicted, though.

Devenport says working out what is the art of tomorrow is not an exact science.

“Thinking towards the future, what is terribly exciting – what is art, what art works are artists making today, and what might they make in the future?” she says.

“Artists are the futurologists of our time and always have been. They’re always thinking ahead. New media, artificial intelligence, installation, performance – art can exist in very ephemeral ways now and that builds on the whole picture. It’s exciting for us to be thinking simultaneously what a collection can be in the 21st century but also what an art museum can be.”