Chris Pearman: Forensic Science South Australia chief retires

He’s been helping keep SA safe for decades, but there’s one high-profile case that Forensic Science SA boss Chris Pearman will never forget.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

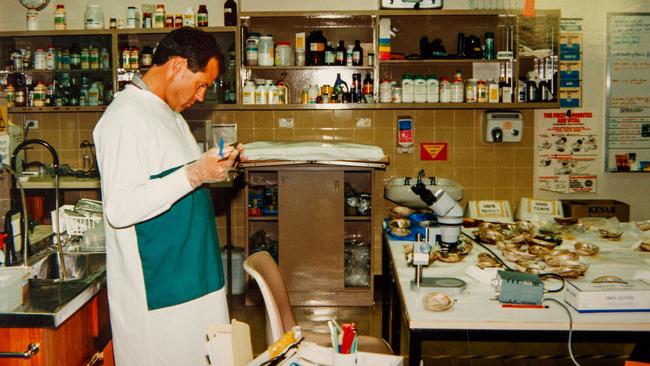

Squinting through the lens of his microscope, fledgling forensic botanist Chris Pearman had an inkling what the dried substance he was looking at might be. It was a type of algae. A relatively rare one called Wittrockellia salina in fact.

His subsequent investigations would discover it was endemic to just a few locations in South Australia. One was in the Glenelg River near Mt Gambier. The other was the Onkaparinga River that gently snakes through Adelaide’s outer southern suburbs on its way to the sea.

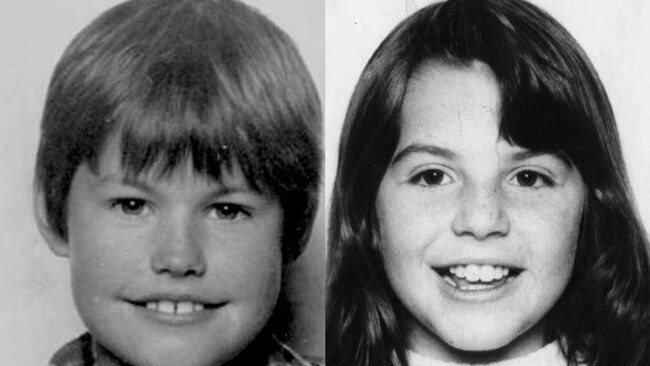

In all likelihood, Chris Pearman was the first police officer to identify a major lead in the 1983 abduction of schoolgirl Louise Bell. The breakthrough, made while painstakingly examining laboratory slides of material vacuumed from Louise’s pyjama top, came five weeks or so after she was quietly snatched from the bedroom of her Hackham West home by a child sex predator.

The algae – along with other microscopic evidence found on the top such as tiny sand granules unique to the area – was clear evidence that Louise’s abductor had more likely than not disposed of her body in the Onkaparinga, a short distance from her home.

It gave police their only major lead in trying to locate the missing 11-year-old and sparked widespread searches that would ultimately prove fruitless – and heartbreaking for her parents.

The irony that the same yellow pyjama top would, some 30 years into the future, yield different, even more crucial forensic evidence that would result in the conviction of Louise’s killer does not escape Pearman, who by that stage had morphed from a junior constable with SA police into one of Australia’s most successful and respected forensic scientists and administrators.

It is an evidentiary scenario that Professor Pearman, who retired as the director of world-renowned Forensic Science South Australia yesterday, has seen repeated many times over his 42-year career. A number of SA’s most notorious, historic cold case murders he was involved in just after they occurred have been cleared in recent years, thanks to astonishing advances in DNA technology and relentless investigations by Major Crime detectives.

As a boy, Pearman was fascinated with biology. From an early age his aim was to become a marine biologist.

He remembers family “field’’ trips to the Flinders Ranges and annual summer holidays at Port Elliot where he started snorkelling around the age of seven. Those two experiences shaped his love of the environment and cemented his desire to one day become a marine biologist. It followed after attending St Peter’s College he would go on to study botany and zoology at the University of Adelaide, graduating in 1978. Tellingly, his subjects included genetics.

Although in the top science stream, he admits to being a fluctuating student both at school and university. His father John was a geologist who taught the subject, so his interest in sciences, particularly biology, wasn’t surprising.

Although his plan was to then study marine biology in Townsville, he ended up working as a copy boy at an advertising agency for a few months after graduating. Then a visit to an old University of Adelaide lecturer, Professor Bryan Womersley, on North Terrace one afternoon altered his planned course in life.

“He told me about a job in the police department. They were looking for a botanist,” Pearman says.

“I thought that sounded interesting and I could do that for a few years until doing further study. I got that job and kind of never left.”

In 1979, SAPOL required all graduates employed to be sworn officers, so Pearman had to complete a six-month adult course at the police Academy. After graduating, he became a botanist in what was then the Technical Services Branch.

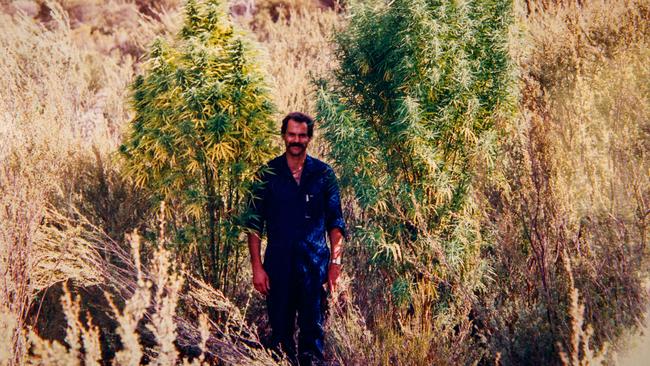

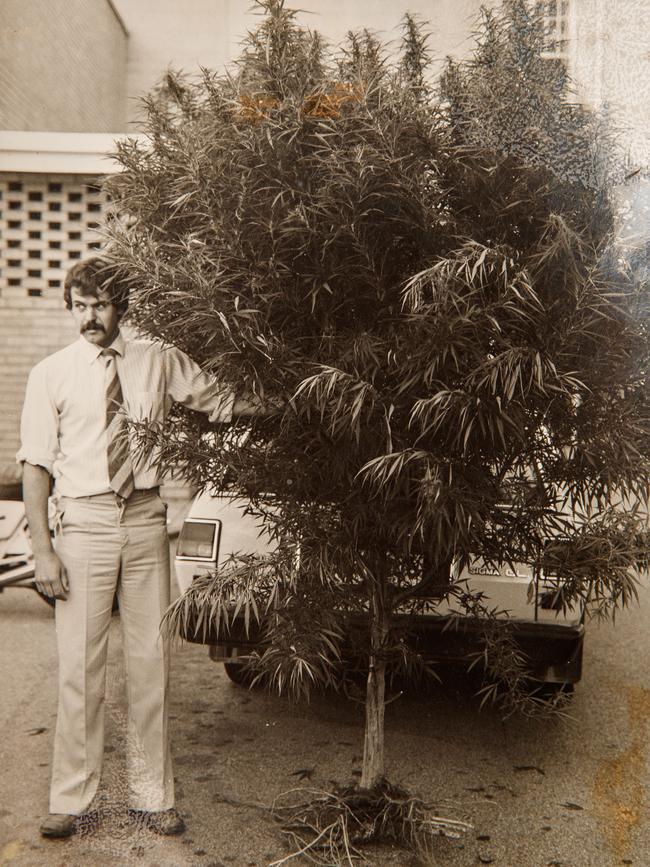

For the next five years Pearman’s duties involved the analysis of botanical evidence in criminal cases, a significant amount of it relating to large scale, outdoor cannabis crops being grown by Italian organised crime syndicates. His work also extended to analysis of evidence involving plants in other outdoor crime scenes, such as sexual assaults.

While ensconced in his specialised field of botanical work in the early-1980s, a storm named Edward Charles Splatt enveloped the branch. Convicted of murdering Rosa Simper in 1977, largely on forensic evidence, Splatt’s lawyers succeeded in having a Royal Commission called to examine his case.

Concluding in 1982, the Splatt Royal Commission highlighted flaws in forensic evidence gathering and analysis processes within SAPOL – finding they were conflicted – and subsequent reviews recommended separating them, along with wholesale changes to procedures and practices. Splatt was also pardoned as a result.

In a major reorganisation in 1985, the independent State Forensic Science Centre – the forerunner to FSSA – was created and Pearman and several colleagues left SAPOL and joined the new unit. While he still harboured a desire to pursue a career in marine biology, he figured he would stick at his new job for a few years.

“I guess I still had visions of sailing up and down the Great Barrier Reef diving,” he says.

As is often the case in life, Pearman met his wife Ann at work in 1986. As a junior scientist, he was assigned to look after the new laboratory technician. The first case they worked on involved extracting vital evidence from a sensitive exhibit. Despite the somewhat unusual circumstances, their relationship blossomed.

They have two children, Tessa, 27, and Tim, 22. Neither child followed their parents’ careers with Tim an electrical apprentice and Tessa a hairdresser.

While initially concentrating on botanical evidence analysis, Pearman says in the ensuing years he slowly found himself becoming more and more involved in other biological evidence recovery and analysis techniques using ABO blood groupings, serum proteins and enzymes to identify and link suspects to crimes. It piqued his interest in this field and developing DNA technologies gave him a glimpse of the future.

In 1998, Pearman was appointed manager of the biology unit and his leadership ensured FSSA was at the forefront of forensic DNA analysis nationally. He managed the unit at the time state and national DNA databases – now vital crime fighting tools – and complex legislation governing their use was introduced and its staff went from a dozen to 35.

He held that position until mid-2006 when he was promoted to the position of assistant director science at FSSA. In November 2012, Pearman was appointed acting director following the tragic death of incumbent Professor Ross Vining in a plane crash in Queensland. He was appointed director in July 2013. On reflection, Pearman remembers the Louise Bell case as being among the most challenging. While the botanical clues he discovered would help the police case immensely, microscopic particles of saliva or blood containing the DNA of paedophile Dieter Pfennig that stubbornly – and thankfully – clung to the fibres of the pyjama top would eventually provide the breakthrough and ensure his murder conviction 30 years later.

“A crime scene investigator showed me some material on it. I could tell it was an algae, but didn’t know which one,” he recalls.

Ironically, Pearman turned to the phytologist who had steered him into his current role for help. Professor Womersley identified the algae, advising him he believed it was endemic to the Glenelg River in the southeast.

“It transpired that Louise Bell had been on a school trip to the Glenelg River around that time. Major Crime were excited about that and we went down there and looked around and collected some samples of the algae. But when we went to look in the Onkaparinga River we found it there as well,” he says.

“There was a whole lot of other evidence on it, such as diatoms (single celled organisms), that told us the Onkaparinga was probably the more likely site that the pyjama top had been submerged in.”

Quite obviously, Pearman had no inkling the pyjama top he first examined in 1983 would one day in the future yield more forensic clues, one that would guarantee a conviction.

“You just have no idea. That is one of the things I feel most fortunate about, being at the forefront of DNA technology over 20 years,” he says.

“To see where it came from when we were doing blood grouping to what we are doing now, the sensitivity and discriminating power of the tests and where it is going into the future, it is mind boggling. It is really rewarding to have been a part of that.”

Although Louise Bell was abducted in 1983, Pfennig did not become a suspect in the case until his arrest for the murder of another child, Michael Black, in 1990. A DNA sample was collected from Pfennig in 2003 and samples from Louise’s pyjama top were subjected to DNA testing in 2005 and 2009, but were inconclusive. In 2011 a number of samples from Louise’s pyjama top were submitted for further DNA analysis using advanced “low copy” techniques at a centre in The Hague, Netherlands. They returned a positive result.

Pearman said he had pondered how the pyjama top came to be found and the sort of individual who was responsible for planting it there to tease and taunt police.

Patterned with small yellow flowers, the sleeveless cotton top was left neatly folded on the front lawn of a house near the abduction site. Louise’s earrings were left at the same location a fortnight after she was taken. “You are privy to some of the discussions with the detectives involved. There were a lot of things that seemed odd and peculiar,” he says. “That was one of them.”

He can still recall when the positive match came back from the Netherlands for Pfennig’s DNA profile – confirming the long-held suspicions of the detectives and scientists involved in the investigation that he had abducted and killed Louise.

“Pfennig had been a suspect for a long time,” he says. “For me, it was a sense of the completion of a circle, if you like, of my career.

“It was committed (in) 1983 and it was resolved just a couple of years ago. In many respects for me, it was closing the loop in my career.”

As for DNA evidence itself, Pearman reckons it has “without doubt” been the greatest ever advancement in forensic science.

“I think the sensitivity of DNA and its robustness, its ability to yield profiles after a long period of time, for me it replaces fingerprints as being the greatest investigative tool for police,” he says.

Pearman has lost count of how many times he has provided expert evidence on DNA in court, but perhaps the most significant was that involving the murder trial of former soldier Damon John Karger in 2000.

Karger was charged with the rape and strangulation murder of Kerryn Ostendorf in 1998. The case against Karger was circumstantial and relied largely on DNA evidence that was ferociously challenged by his lawyers.

Found lying face down on her bed, Ostendorf’s clothes had been cut, most likely by scissors, and torn from the back. She had been strangled with her own camisole.

Pearman oversaw the examination of the clothing that found two minute blood stains from which DNA was extracted that matched Karger’s, who had already been identified as a suspect by detectives. They were located inside her blouse near the line of cut.

The DNA was extracted using the now obsolete Quadruplex system shortly after the murder and then, in 1999, by a new, much more sensitive system called Profiler Plus.

During a voir dire hearing prior to the trial in 2000, the defence unsuccessfully challenged the reliability and accuracy of the Profiler Plus system, the competence of FSSA and its scientists, and other aspects of DNA technology.

In his reasons for allowing the evidence at trial – which ran for seven months – Supreme Court Justice Ted Mullighan upheld the DNA testing method and praised the FSSA scientists involved in the case, singling out Pearman for his clear and informative evidence given during 38 days in the witness box.

Mullighan’s ruling has become the beacon in case law when the accuracy of DNA evidence is ever challenged.

Pearman, manager of the biology unit at the time, remembers the case well, including “the tiny, 1mm pin pricks of blood” evidence recovery staff found on the blouse.

“The offender used the scissors to cut the thick hem at the bottom of the blouse and probably pricked himself on the finger and left the two pin pricks of blood,” he says.

“Karger quickly became a suspect. He knew the victim and had rung her many times that night, and the calls stopped about the time the pathologist thought she died.

“Our DNA system at the time only looked at four loci (regions of the DNA molecule) and it was the same as Karger’s profile.

“In 1999 we introduced our new technology, Profiler Plus, that looked at 10 loci and we knew by then the defence was going to challenge the DNA evidence.

“We knew it was a two-edge sword, but if he was genuinely innocent then you have a better chance of showing that with a 10 loci system than a four loci one.

“We tested it and he still matched. The defence used that as a test case for DNA evidence, particularly the new technology. The judge accepted it and Karger was found guilty.”

Such was the importance of the case, many criminal trials around Australia that involved DNA evidence were adjourned pending the outcome of the Karger trial.

Besides convicting Karger, the validation of infinitely more sensitive and accurate Profiler Plus system paved the way for the establishment of DNA databases – another extremely valuable tool for police.

Introduced in 1999 after the Forensic Procedures Act passed state parliament allowing samples to be retained, SA’s database now has 148,000 person samples from either convicted criminals or suspects – 8.5 per cent of SA’s population – and 25,000 crime scene samples. The national DNA database holds 992,000 person samples and 736,000 crime scene samples.

Such is the effectiveness of the SA database now, 70 per cent of new crime scene samples are now being linked to a person on the database – once again confirming the fact that the vast majority of crime is committed by a relatively small number of recidivist offenders.

More recently, Pearman has overseen the introduction of familial DNA technology. It enables police to identify an offender using the DNA of a close relative who is already on the database. First used successfully in 2015 to catch and convict the North Adelaide rapist, it has also been responsible for breakthroughs in several cold case murders – including the 1993 murder of Suzanne Poll.

“That is another area we have led Australia,” Pearman says. “The North Adelaide rapist conviction was the first in the country using this technology.”

The breakthrough came through the work of FSSA scientist Dr Duncan Taylor, who developed the STARmix DNA interpretation software in conjunction with two colleagues in New Zealand’s Institute of Environmental Science and Research.

Like the Louise Bell abduction, Pearman was also involved in the Poll investigation from its infancy. While coy about discussing it because it is still before the courts, he says “hundreds” of suspect samples had been tested over the years but none had ever matched the profile obtained from the blood of the offender at the scene.

“Because it was put on the general database and there were no hits, the thinking at the time was she may have been murdered by someone who had since died,” he says. “It was quite pleasing to see a suspect arrested after so long.”

Pearman and his team at FSSA are intimately involved with Major Crime’s cold case initiative Operation Persist and are actively retesting many, many exhibits from unsolved murders.

“There are a number of cases where major crime has identified where we can provide assistance,” he says. “It is time consuming and painstaking going through the old case files, but very worthwhile given the sensitivity of our current tests.”

Such is the rapid improvement in DNA technology, the cold case exhibits are now being analysed using an enhanced and even more sensitive system called Globalfiler, which looks at 24 loci in a molecule.

While DNA phenotyping – identifying the features of an individual from their DNA profile – is the next step in DNA’s evolution, Pearman is a little sceptical.

“The technology means it takes two to three days to develop a profile and it gives you a ridiculous amount of information you don’t need to solve daily cases. There will be niche value in a small number of cases,” he says.

At present phenotyping can only indicate a number of features, such as eye and hair colour and geographical ancestry, but technology available in the US is now developing a facial image using DNA markers.

While there is always satisfaction when a cold case is cleared and other offenders are quickly brought to justice because of his work, a good number of cases have troubled Pearman throughout his career.

Snowtown was one, simply because of the enormity and ghastliness of it. The Stuart Pearce quadruple murder case and its lack of forensic evidence is another. The tragic murder of tiny Khandalyce Pearce also resonates because of its gruesome nature and the intense pressure his team were under to obtain a DNA profile from her remains to identify her and help police solve the mystery.

And Pearman says he has learned to live with the “CSI effect”, whereby the public expect every crime to be solved within an hour. “It is problematic for us. The popularity of the shows were very good for us, they bolstered the Forensic and Analytical Science course at Flinders University but it created a false impression of forensic science on several fronts,” he says.

“One is that there is always forensic evidence that will always solve the case and it also created an impression of infallibility for forensic science, which is not the case.”

Behind Pearman’s affable manner lies a razor-sharp intellect. His ability to distil complex scientific principles and methodologies, and acquaint a layman with them is both renowned and keenly anticipated by prosecutors.

Combined with his softly-spoken, yet authoritative demeanour, he has silenced many a cranky defence barrister while at the same time assisting baffled jurors as he meticulously educates them in the intricacies – and inescapable truthfulness – of DNA evidence.

At 63, Pearman simply feels it’s time to go. He plans to spend more time snorkelling, fishing and enjoying his favourite beach – the very things that sparked his interest and fascination with biology almost six decades ago.