CFS chief Mark Jones on fires, Scotland and his controversial appointment

Mark Jones’s appointment as CFS chief was derided by some, but the Scotsman proved his worth in one of SA’s worst fire seasons

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was while driving along the Onkaparinga Valley Road in the Adelaide Hills in the wake of last year’s terrifyingly destructive Cudlee Creek fire that the still new Country Fire Service chief Mark Jones really began to understand what this organisation means to South Australians.

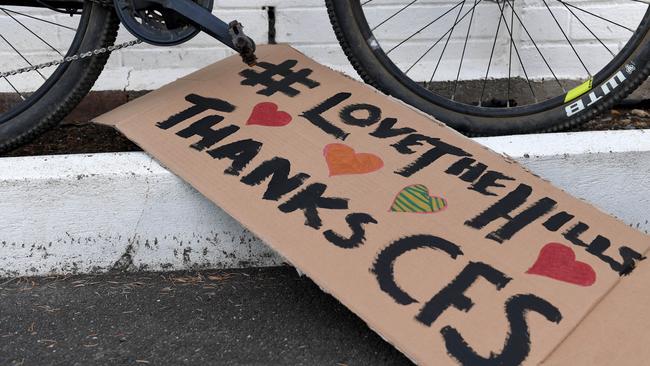

As ever, the volunteers of the CFS had been out in force during the fire. Risking life and limb in the service of others. Saving lives. Saving homes. Saving towns. Sitting in the CFS’s city office on Waymouth Street, Jones, a Scotsman, still marvels about what he saw that day. The signs of gratitude on the side of the road.

“Thanks for saving our jobs firies,” one read. “God bless the CFS” hanging from a church at Woodside, another.

“You know, it was quite moving, and something I’d never really encountered before,” Jones says. “In other places I’ve been, you had a bit of professional pride, but this was something on a different scale altogether. Another order, really.”

The 59-year-old Jones was appointed CFS chief in August last year. His appointment was greeted with a level of scepticism from many. The CFS Volunteers Association wrote to all its members saying Jones didn’t meet the criteria for the job. One of the criteria was that the new chief should have “extensive knowledge and understanding of the Australian topography in relation to fire behaviour”.

Jones was a highly experienced firefighter and commander, but the vast bulk of his working life had been spent in the United Kingdom where he had worked in and run metropolitan fire services.

Greens MP Tammy Franks tweeted that she had to check it wasn’t April 1 when Jones was appointed because of his lack of “bushfire experience”, even though he had served as chair of the International Forest Fires Commission.

Jones is the phlegmatic sort though. He also does a good line in understated self-confidence. So, if he was at all rattled by the less-than-hospitable welcome to South Australia it would be hard to spot.

“I think my appointment was greeted with much derision by some of the media and some of the stakeholders here,” he says. “And I was a wee bit confused by that, obviously. When I turned up I walked into a load of abuse, almost demanding to me why I got the job. And, of course, as a candidate, you never know why you got a job. All you know is they offered it to you.”

But perhaps there was something else at work as well.

“One person said to me, ‘Well, it could have been worse, you could have come from Victoria’. So it was perhaps also a bit of xenophobia.”

If Jones wanted the chance to prove himself, to show his skills, his timing was perfect. He walked into one of the most catastrophic fire seasons ever experienced in South Australia. From the fire in Yorketown in November, through Cudlee Creek and Kangaroo Island, South Australia was ablaze through spring and summer. Three lives were lost in the fires, 179 homes were destroyed and 200,000 hectares burnt. Untold numbers of animals were killed.

It was a lot to take in for a bloke who had just arrived in South Australia. Even one who had studied the state and its fire history “really hard” before arriving.

Still, Jones holds that a “fire is a fire”. “I came here to do fire command, so I shouldn’t be daunted by that.”

What was different was the sheer scale of the fires. And because he had only just started, he hadn’t had the chance to meet the 55 commanders on the ground who are spread all over the state.

“So you feel a little bit bereft for not having talked to them,” he says.

Jones was quickly thrust to public prominence as one of the voices of the fires, standing alongside other emergency service leaders and Premier Steven Marshall. His calm measured tones offered a reassurance that many others weren’t feeling.

It was, he says, a “somewhat chaotic” time.

“From the 20th of December for two months really my life was not my own,” he says. Not that he’s complaining, or looking for sympathy.

“All of my officers did exactly the same,” he says. “Every single one of them just rose to the occasion. They sacrificed all sorts of family events, milestones, you know, just to put the state first.”

The thing about being a fire commander is that it’s your job to put other people in harm’s way. Jones has three decades of experience as a firefighter. He was brought up in the small Scottish village of Burghead, about 30km east of Inverness. At university he studied pharmacy, but dropped out when he realised “I’d be meeting sick people every five minutes for the rest of my life”. He tried a few jobs in agriculture and fishing, then saw an ad in a local paper for firefighters. At the time he was a “pretty forceful amateur boxer” and decided to apply.

He moved to Aberdeen for the job and was there for 10 years. Jones loved the job. Even its inherent danger didn’t phase him or the other firefighters he worked with. He admits most firefighters are “a wee bit crazy”.

“You’d never really felt the danger, even though you knew it was insanely dangerous as a profession,” he says. “When you sign up, you sign up to run into buildings, other people are running out of. That’s part of the deal. And the public expectation is that you’ll be brave.”

It was when he moved into officer roles that he started to worry about the danger of the job. He says when firies jump in the truck, their first thought is “I hope this one’s a good job”. But that changes when you are in charge.

“When I was an officer, I would look over my shoulder and see these three or four young faces in the back and think, ‘Good grief, I hope this isn’t a big job’.”

After a career working in the north of Scotland, Jones moved south in 2005 to become deputy chief in Essex. He says it was a job with a lot of challenges.

“They get fields on fire there, too,” he says. “But they have oil refineries, military bases, high-risk establishments, nuclear establishments.”

Jones was in Essex for five years before being promoted to chief officer in Buckinghamshire in the southeast of England. He was there for five years as well, in a job that had its moments of controversy. There were clashes with unions, national strikes and budget cuts.

In 2014, Jones was awarded the Queen’s Fire Service Medal, the citation saying he had “produced better outcomes for the community whilst driving down costs”. He was also lauded for revolutionising the service’s “approach to community safety”, which had installed 20,000 free smoke alarms in homes and delivered road safety messages to young drivers. He retired, for the first time, in 2015 when he was 53 because he was “kind of forced to by the taxation regime and pensions in the UK”.

It didn’t stick. A keen fisherman, even he became bored with nothing to do. He applied for a job in Canberra. He had been to Australia a few times for conferences and spent some time with Adelaide’s Metropolitan Fire Service in 2008.

“Having nowhere else to benchmark it against, because we hadn’t lived in Australia before, we thought it was OK,” Jones says of Canberra. His job there was to initially review the Canberra fire service before being asked to reform the ACT Emergency Services Agency. During that time he was introduced to the Australian term “toecutter”, made famous by the mad bikie leader in the original Mad Max film.

“I didn’t know what it meant,” Jones says. “Somebody explained that to me. In any case, by the time I left that I’d made many friends right across the sector.”

He retired again after two years in Canberra. Moved back to England. Built his dream house with his partner and soon-to-be-wife Elizabeth in Milton Keynes. Again, it didn’t take. He took a job as head of resilience and specialist assets for the London Ambulance Service. He was only there for seven months when a job ad on the internet caught his eye. “And I kind of felt I had unfinished business with Australia,” he says.

Jones says to some extent he understood some of the scepticism surrounding his appointment, but decided not to “try to win them over, I just tried to do the work”.

The president of the CFS Volunteers Association, Andy Wood, says any resistance to Jones wasn’t personal.

“We were nervous about the appointment, in regard to the process,” Wood says.

Wood says any doubts about Jones quickly evaporated. “He was very much up to the job,” he says. “He has a presence about him, the presence of a leader and a confident leader.” Wood says Jones held no grudges, despite what could have been a rocky start.

Jones, for his part, is effusive in his praise of the volunteers.

“We have just over 10,000 active volunteers,” he says. “On our worst days last summer, we had six and a half thousand of them in the field. That’s incredible. What a commitment to the state these people were making. Men and women who just walked off the job, walked away from their families on Christmas Day. And put fires out.”

During the worst of the fires, his worry for the safety of volunteers made sleep difficult. It was, he says, different to the concern in his earlier days about sending professional firefighters into dangerous situations.

“I was checking my phone every hour, every hour through the night, in case someone more got hurt or injured or burned,” he says. “It almost felt like the first time your kids went out on their bicycles on their own that you felt some extra weight of parental responsibility for their wellbeing. I was surprised by it. I didn’t know I’d feel like that.”

But he also realised that he needn’t worry. That the volunteers knew what they were doing. “Because actually, I’d put them up against any paid firefighting force in the world. They are magnificent.”

Another fire danger season has already started in some parts of the state. Tomorrow restrictions will begin in more areas including the Yorke Peninsula, the Upper South East, Murraylands, Mid-North and the Lower Eyre Peninsula. On December 1, the Lower South East, Mt Lofty Ranges and the Adelaide Metropolitan area will join them. Like everyone else, Jones is hoping there is no repeat of last year’s infernos.

There have been two major inquiries since then, with a Royal Commission examining the national implications and former Federal Police commissioner Mick Keelty looking at the SA response. As part of its answer to Keelty, the state government is spending $100 million on new trucks, better communication equipment and thermal-imaging cameras.

The Royal Commission warned fire danger was only likely to increase as global warming accelerated. Jones worries about the number of people living in bushfire-prone areas and says he was surprised by how many didn’t have insurance. He says both those things need to change.

As for the CFS, it will continue to do what it has always done. “We haven’t changed too much, bearing in mind most of our responses last year were successful.”

At the very least, he will be hoping for a less stressful Christmas Day. Last year, he and Elizabeth headed to the staging point at Cudlee Creek and the command centre at Mt Barker to be with all the volunteers who had foregone their traditional Christmas lunch to safeguard the community.

“And you know what? Great day. Great Christmas Day. They were giving their day up, so would we.”

And this year no one can say he doesn’t have experience in battling bushfires.

“Funnily enough, some of the people who were my most vociferous critics when I took up the post, I work really closely with now and greatly respect. So it’s just sometimes you have to get to know people.”