Can Monarto Zoo save the southern white rhino?

MONARTO Zoo is stepping up its bid to help save one of the most hunted and endangered creatures on Earth, the southern white rhinoceros.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY weigh up to four tonnes, stand as tall as a footy player, charge at up to 50km/h, and channel all that force through a horn that grows to a metre in length.

No wonder they call a group of rhinos a crash.

But if all that sounds like the white rhinoceros is one of the world’s most terrifying animals, then Zoos SA chief executive Elaine Bensted begs to differ.

“They’re like labradors,” she says affectionately.

And for one of the most hunted and endangered creatures on Earth, that’s a problem.

As more have been killed, so many more babies and young ones have been raised by humans in African orphanages, teaching them to trust people.

Released back into the wild, that puppy-like faith, and their poor eyesight, has made them even more vulnerable to the poachers, who hunt their horn.

It’s not bone, but keratin — the same material our hair and nails are made of — and it is extremely valuable, peaking at a reported $65,000/kg in 2012. The Chinese and Vietnamese are driving the trade with a belief it cures fever and convulsions.

It’s a crisis for one of the world’s most magnificent animals, and it’s drawn in high-profile activists, including Prince William and Prince Harry. Poachers even raided a French zoo this year to kill a rhino and cut off its horn.

Now, Monarto Zoo is stepping up its bid to help save the rhino as part of its multimillion-dollar Wild Africa project that it promises will give visitors the best African wildlife experience outside of that continent.

Monarto and Taronga Western Plains Zoo in NSW have partnered with the Australian Rhino Project to create an “insurance population” in Australia to try to guarantee the survival of the species.

The plan is to relocate 80 endangered southern white rhinos from Africa during the next few years to bolster the 56 currently in Australia and New Zealand.

We’ve come to Monarto’s rhino enclosure to see how the rescue mission is progressing.

Director of Life Sciences Peter Clark, who is standing at a wooden gate at the back of the enclosure, calls to the four rhinos inside, and they all amble happily up to the fence waiting to be patted and attended to. Labradors indeed.

But despite this placid nature, the keepers still treat them as dangerous animals.

Their size alone gives them the ability to crush and cause injury — as was shown earlier this year when Monarto’s youngest southern white rhino, Tundu, was killed during some “rough and tumble” play in her enclosure.

With just five remaining southern white rhinos and two southern black rhinos, the accident was a cruel blow to Monarto’s breeding ambitions.

“Every female you take out of the breeding population has a disproportionate effect because only a certain number of females are old enough to breed, or not too old to breed,” Clark explains.

Clark makes annual trips to Africa and, through the zoo, supports projects to counter the poachers in South Africa’s Kruger National Park, and also the reintroduction of 10 black rhinos in Kenya.

There, the zoo pays for the rangers’ wages and life insurance, given the dangers they face from ruthless poachers. One has already been killed.

Clark estimates about three rhinos are lost every day, with at least 1150 killed in 2016.

In the first half of this year, 529 were killed in South Africa alone. These numbers were slightly down from previous years, but with junder 21,000 white rhino left, the death toll is clearly unsustainable. The western black rhino has already been declared extinct, in 2011, and only three northern white rhinos — which cannot breed — remain.

“It’s getting to that stage where our rhinos haven’t got long to live,” he says.

Monarto got its first white rhino in 2000, and now has five white. It hopes to have about 30 at the end of the project.

“There are about 50 white rhinos in Australia and New Zealand and we’re hoping to get that number up to 100 to 120 across the two countries,” Clark explains.

“That should sustain us with proper breeding for at least 70 to 80 years. During that time, should the situation get to the real extreme over there (in Africa), then we’ll be considering repatriation.”

The Australian Rhino Project was founded in 2013 and announced its ambitious plan with Monarto Zoo in April 2016. But it has hit a few snags, and key issues about quarantine and the sourcing of the animals remain to be resolved.

Six rhinos were due to be brought by plane from South Africa by the end of last year, where they would be quarantined at Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo before three were then transferred to Monarto.

But one of the biggest problems has been meeting Australia’s strict biosecurity regulations.

Diseases and a risk of bovine tuberculosis mean South Africa does not have approved arrangements to export rhinos to Australia.

That means the rhinos would need to spend about three months in Africa, and 12 months in a third country, possibly the US, to meet quarantine requirements before they could be considered for entry to Australia.

Bensted, who also sits on the board of the Australian Rhino Project, said an exact time frame for the first intake of rhinos is not known but “we’d hope for 2019”.

Funding is critical to the mission. The Australian Rhino Project will pay for the transportation of the rhinos by air, which is estimated to cost up to $50,000 per animal, depending on the age of the rhino and the flight path.

Zoos SA and the rhino project will jointly cover the costs of building appropriate facilities for the additional rhinos, while the ongoing maintenance and care will be covered by the zoo and its team of more than 30 keepers.

Monarto held a Rhino Gala in January with cycling star Anna Meares to raise money for its quarantine facility.

In the meantime, Zoos SA is forging ahead with the logistics and preparation to house a new group of rhinos at Monarto.

And Clark is convinced that the end result will be stunning.

It was in 2008, when he was in a helicopter flying over Monarto’s 15sq km property chasing an escaped white male rhinoceros named Satara, that Clark says he was able to see the very clear similarities between Monarto and Southern Africa.

Satara had gone on a jealousy-fuelled rampage after his mate, Yhura, was paired with a younger male. Eventually he wandered back into his enclosure the next night after crashing through some small internal fences, and being shot with five tranquilliser darts throughout the day.

As Satara’s “big day out” showed, Monarto certainly had the space to handle the animals. And so it will be out the back of the zoo’s current facilities that the rhinos will become a feature of the new “Wild Africa” precinct.

“It was an opportunity for us to start thinking about a worthwhile insurance population because having that bit of land that we were going to use for a safari experience just fitted in so well,” Clark says.

“There won’t be anything like this in the world. This will be the biggest experience outside Africa.”

The precinct is planned on the eastern boundary of the zoo and will feature a safari and accommodation experience, which will allow visitors to become immersed in the “sights, smells and sounds of the savanna as they travel across the open plains through herds of animals seemingly free to roam in nearly 500ha”.

About 150 animals, from lions to cheetahs and hyenas, are already waiting to move into the area, which will be kept as natural as possible, with large numbers but fewer species.

“You might see a ... tower of giraffes, a crash of rhinos, a dazzle of zebras,” Clark says. “You’ll be able to see them in the morning when you wake up and at night when you go to sleep.

“The thing that we’re trying to do here is not just give (visitors) the opportunity to see them in a more natural state, but to get up close and to appreciate the variety and difference. They’re worth saving, looking out for them, trying to make sure they survive.”

Bit by bit, the new space is being developed. An external perimeter fence, stretching 10km around the property, is now complete, and awaiting a feral-proof skirt and overhang to be added. Inside that fence will sit a 50m wide border of scrub, and then the escape-proof heavy duty steel internal fence.

At least 40,000 tonnes of soil has already been moved to flatten the land, 80,000 trees have been planted, and a deposit has been put on a “big shed”. The shed will be home to a new quarantine facility, where the rhinos will be kept following quarantine in a third country.

The building will be huge — 1000sq m — and allow keepers to quarantine 10 rhinos at a time. “If the rhinos have a relationship they will be kept together but if they haven’t and they’re bulls, they will be kept at different ends of the building. They just fight when females are around.”

Bensted stresses there’s nothing simple about the operation to bring in the rhinos.

Nor is it just a matter of finding a country which could keep the rhinos in quarantine for a year. The flight would need a stopover en route and quarantine would have to be agreed for that country as well.

Options for quarantine included the US, at an accredited zoo, but “there’s a range of good zoos in America and Canada, New Zealand and Europe”.

The other big question is where the rhinos will come from, to maintain genetic diversity at about 90 per cent. Monarto brought in more rhinos in 2002 from Kruger National Park in South Africa — which again is an option, as well as orphanages and private holders. Females of breeding age — those over three years old — rather than bulls will be needed for the Australian breeding program.

The process of building a larger herd will take time. A female rhino bears a single calf, and gestation can takes between 12 and 18 months. She will mate again about three years later when the calf is grown.

The Australian Rhino Project is mostly focused on white rhinos but Bensted says Monarto is also considering the need for some female southern black rhinos — because it currently has two males.

“Only Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo is involved in breeding blacks in Australia and we’d like to join them,” she says. “It would be fantastic if either from another zoo in the world or from Africa (we could) be able to look at supplementing our blacks.

“They’re a little more challenging. They’re not the easiest to transport — whites are a bit more tractable and quiet, they’re big but they’re calmer.”

So if the whites are labradors, what about the blacks?

“Black rhinos are more tentative and nervous by nature,” she says. “So they could be compared to a greyhound or whippet.”

HISTORICAL LINKS

South Australia has a long history with the rhino — all the way back to 1886 when Mr Rhini arrived after Adelaide’s zoo director R.E. Minchin bought him from Borneo for £66.

“He is as tame as a pig, and only 18 months old, but strong as a horse,” the director told the local press at the time.

Minchin, a great-great-great-grandfather of the performer Tim Minchin, wrongly displayed Mr Rhini as an Indian single horn rhino all his life, when in fact he was from Java. The last Javan rhino in captivity as it turned out.

“Only 40 years after his death did they correctly identify him,” says Monarto Zoo’s Geoff Brooks. “Now he’s the little guy in the SA Museum.”

Brooks has been a long-time admirer of the rhino and has written a book, Game in Transit, a history of the rhino in South Australia.

After Mr Rhini, who died in 1907, two black rhinos were acquired by the zoo, in 1929. The female, Dolly, died in Melbourne on the way, and the male, Peter, only survived two weeks at the zoo. The next to come was another black rhino, Sinya, in 1947, when there were 65,000 black rhinos in the world.

“By the time he left in 1981, they were critically endangered,” Brooks says.

“So many people see them as nothing but a great big grey lump, but they just fascinate me. They’re such a prehistoric looking animal.

“Once you get to know a rhino they are the most amazing creature — they are personable, they are big, they are gentle,” he says.

“You call them and they’ll run up to you. They like the attention. They’ve all got personalities. They are an amazing creature.”

Monarto began bringing white rhinos to the zoo in 2000. Several babies have been born and the zoo plans to expand its herd as a way of protecting the species.

“It’s worth more than gold at the moment,” says Brooks of the rhino’s keratin horn, which is targeted by poachers. He points out it has no more medicinal properties than your hair or fingernails.

The South African and Zimbabwean government are trying to legalise the sale of the horn, he says. (South Africa has since legalised the sale). That might cut the price, but would increase the market and make things worse for rhinos which were now not even safe in zoos.

One died in France died horrifically this year when it was shot and its horn cut off.

Game in Transit by Geoff Brooks, published by Wakefield Press, $39.95, out October.

BACK FROM THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION

Past the main attractions and down a beaten track at Monarto Zoo, is where the insurance populations vital to South Australia are being established, with animals bred there being released back into the wild.

If it wasn’t for Monarto, the state wouldn’t have bilbies and there would be fewer yellow-footed rock wallabies.

Conservation manager Liberty Olds is working with Mallee emu wrens, which are “functionally extinct” after the 2014 wildfires wiped out their habitat in SA.

The tiny birds, which are about “the size of a 20 cent piece” and weigh about 4g, have had a purpose-built aviary built for them at Monarto with Federal Government funding in partnership with Rotary.

“We need to learn how to house them and keep them if their habitat is wiped out in fires and the species is lost altogether,” Olds says.

Curator of Conservation and Native Fauna Phil Ainsley, whose father was a curator of reptiles during the 1980s at the Adelaide Zoo, says while visitors come to the zoo to see the big species, it was the little ones, like pygmy blue tongues, they have saved from extinction in a world-first for conservation.

“Pygmy blue tongues is a species thought to be extinct until 1992,” he says.

“Last year we achieved the first breeding in captivity, which was a fantastic achievement.

“It’s really important for people to see just how diverse Australia is but also some of the threats and the things that are happening.

“Zoos across Australia are playing really important roles in the conservation of Australia’s biosecurity.”

Keepers at Monarto have kept 1500ha of remnant bushland on site to protect declining woodland birds that naturally flock there, as well as work with threatened plant species such as the Monarto mint bush.

“Our priority is our own backyard,” Ainsley says. “If no one else is working on the species in SA then that’s definitely an area we need to look at.”

Zoos SA chief executive Elaine Bensted said some of Monarto Zoo’s most important conservation work for native species takes place in a dedicated breeding facility.

“We’re proud to be working to secure a future for some of Australia’s most endangered animals like Tasmanian devils, black-flanked rock-wallabies, brush-tailed bettongs, western swamp tortoises, greater bilbies and pygmy blue-tongue lizards,” she says.

In June, 25 Warru (black-flanked rock-wallabies), from a population established by Adelaide Zoo-bred animals, were released in the APY lands.

“Zoos SA has bred more than 15 species for re-release into the wild in SA, nationally and internationally, including greater bilbies, western swamp tortoises, yellow-footed rock-wallabies, orange-bellied parrots, regent honeyeaters, stick-nest rats and the Przewalski’s horse,” Bensted says.

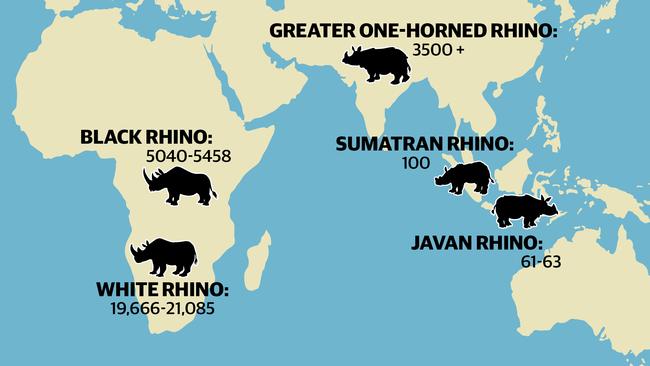

SPECIES OF RHINO

WHITE RHINO

The second-largest land mammal resides in just four countries including South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Kenya. Northern white rhinos and southern white rhinos are genetically distinct subspecies and are found in two different regions in Africa. There are only three northern white rhinos left in the world, all in captivity. Southern white rhinos, which grow between 1.5m-1.8m tall, are classified as near-threatened.

BLACK RHINO

European hunters are responsible for the early decline of black rhino populations as farmland was developed. Now critically endangered, up to 5400 remain. They grow to 1.6m tall and live in tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, deserts and dry shrub lands.

SUMATRAN RHINO

The smallest of the living rhinoceroses grow between 1m and 1.5m tall, and are the only Asian rhino with two horns. They are covered with long hair and are more closely related to the extinct woolly rhinos. Sumatran rhinos are critically endangered, with fewer than 100 remaining due to poaching. The two different subspecies, the western Sumatran and eastern Sumatran, now cling to survival on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. Experts believe the third subspecies, the northern Sumatran rhino, is probably extinct.

JAVAN RHINO

The most threatened of the five rhino species, there are only 58 to 68 individuals surviving in Ujung Kulon National Park in Java, Indonesia. Vietnam’s last Javan rhino was poached in 2010. A dusky grey colour, the Javan rhino has a single horn of up to about 25cm long. It is between 1.4m and 1.77m tall.

GREATER ONE-HORNED RHINO

This is the largest of the rhino species, which was pushed very close to extinction in the early 20th century. By 1975 there were only 600 individuals surviving in the wild. Rigorous conservation efforts has increased their numbers dramatically, with a population of more than 3500 in the Terai Arc Landscape of India and Nepal, and the grasslands of Assam and north Bengal in northeast India. The rhino is identified by a single black horn and grey-brown hide. It grows to a height of 1.7m to 2m, and weighs up to six tonne.

Source: World Wildlife Fund