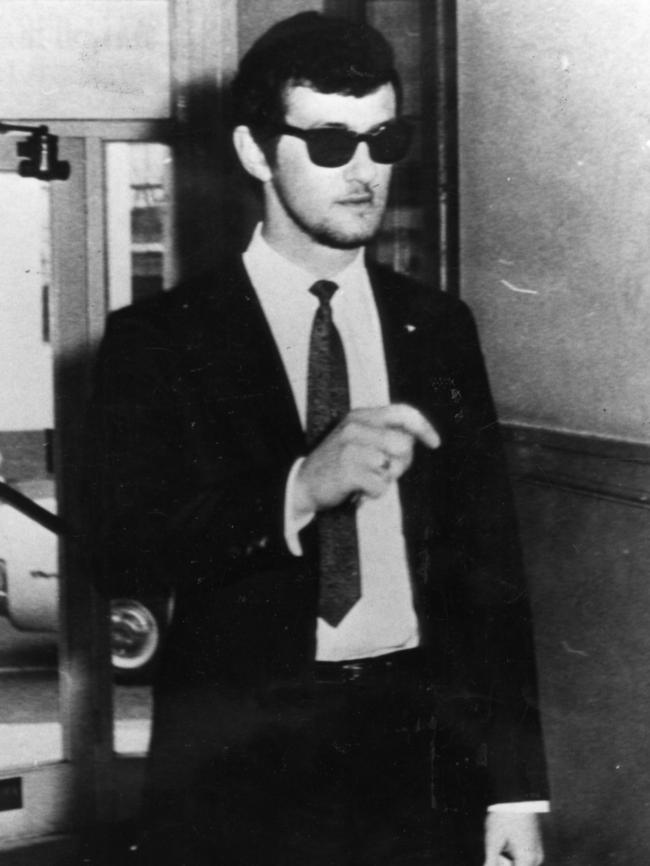

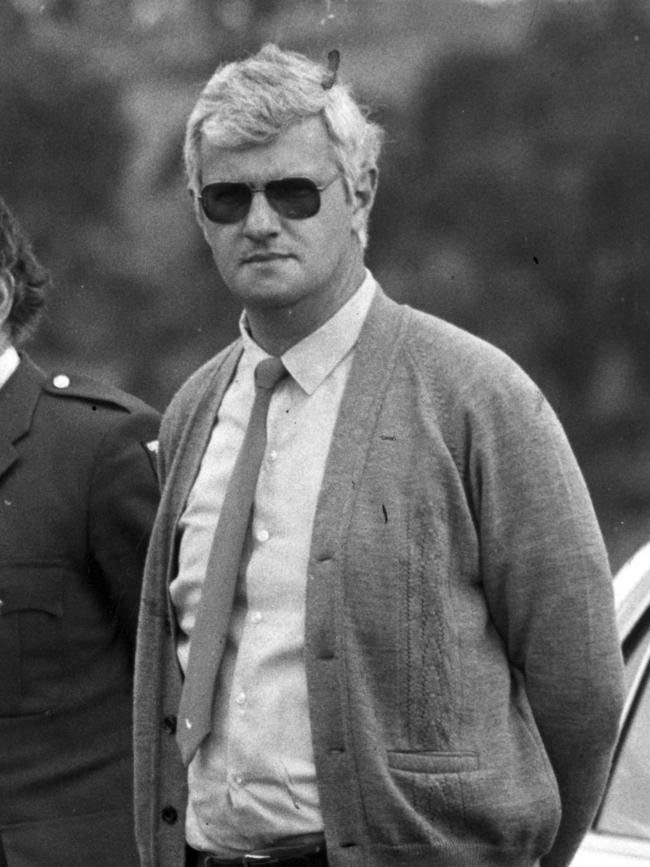

Bevan Spencer von Einem: Debi Marshall visits Port Augusta prison

He denies any knowledge about The Family, but convicted killer Bevan Spencer von Einem licks his lips and smiles and I ask him simply: “What about you Bevan, what’s your story?”

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

This is an edited extract taken from Banquet: The Untold Story of Adelaide’s Family Murders by Debi Marshall published by Vintage Australia, $34.99

I scribble notes and read again what the criminal profiler, Kris Illings-worth, has advised me. “Be professional. Listen for lies. As soon as you walk in the room, the person will be assessing everything about you, looking for your strengths and weaknesses. You need to impress him with your knowledge, your organisation, how you talk to him. Don’t be scatty or flustered, even if you can’t remember anything. Know the details of the relevant cases. If you’re not knowledgeable he’ll exploit or manipulate this to his advantage or amusement.”

I make yet another cup of tea and keep reading. “Show as little of your personal self, your opinions, views, personal background to him as possible. Give him nothing to work with. Keep it always at a high professional level, no matter how charming or charismatic he may appear.”

I think of Paul, Bevan Spencer von Einem’s friend, who describes him as charming and charismatic. “Don’t let your emotional guard down. Don’t let him into your world. Dress blandly with little make-up. No jewellery. Give him nothing to be distracted by. Psychopaths need interest, stimulations, distraction because they quickly bore. This way you can maximise his interest in the case and what you’re saying. Lastly, stay in control. This is really important. Stay in control of yourself, how you’re interviewing him and of the situation. Don’t let him take control by hijacking the topic. Stay cool, calm and unflappable.”

Cool, calm and unflappable? I’m going to be totally alone in there, apart from the guards. I’m not allowed a phone or notes. I’m not allowed anything at all. If something goes wrong, I’m at the mercy of the system to help me and have no way of letting the outside world know. A former Port Augusta lifer, since released, has told me that all the general duty guards carry are handcuffs. That’s not much comfort to me in the event of an assault.

Dawn finally rises, scarlet hues staining the sky. By 7am I fret that I will forget what to ask, and I scribble names on my hands to help my recall. Don Dunstan. The Beaumont children. The businessman. Mr B. Concentrate. Breathe. Breathe.

He has been incarcerated for 37 years, at Port Augusta for 14. Time turns slowly in the Outback.

The Port Augusta prison houses more than 500 inmates of mixed gender, including high to low security risks, special needs prisoners and a significant Indigenous population. A select few prisoners like von Einem are held in protective custody and segregated from the mainstream for their own safety from those who itch to bash the paedophiles – rock spiders in prison slang – or pour boiling water over them in the kitchen, or piss in their food.

It’s hard yards in here. If there is trouble from the inmates, the riot squad, kitted up in overalls, boots, knee and elbow pads, their identities disguised by drop-down visa helmets and balaclavas, and carrying zip ties, batons, Perspex shields and gas canisters, move in to subdue resisting prisoners. If that doesn’t work, high-pressure water hoses are deployed. But it’s boredom that eats at the inmates, mostly, and von Einem’s life inside is beyond boring.

Although he is permitted to mix with prisoners, he is locked down in his cell at 4.30pm and not allowed out until 8.30 the next morning. Year after dreary year, he has watched major world events through the prism of a small television: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the death of Princess Diana, September 11 and beyond.

He fixes me with a friendly stare before appraising his shapeless prison uniform of florid orange windcheater and green sweatpants and launches into a charm offensive. If only he had had more notice that I was going to visit, he says, he would have taken further care with his dress and worn a cologne aftershave.

If only he had known. He catches me with a quiet question, slithering in under my guard. “Do you still live in Hobart?”

How does he know where I live? I think, and I stumble for the briefest moment, reminded of the advice: Tell him nothing. Don’t let him under your guard.

“No, I’ve moved,” I say but he jumps in immediately.

“Oh? When did you move? I saw you on a television documentary talking about the Snowtown thing from there just the other day.”

The Snowtown thing. The documentary in which I was interviewed talking about my book, Killing for Pleasure, about the depraved sexual torture and murder of 12 people.

Why, I wonder, do authorities allow von Einem to watch this type of show, allowing him a voyeuristic venture into the darkest heart of serial killers?

I change the subject. “Tell me about your father, Bern. What was he like?” It’s a loaded question. Aloof, dictatorial fathers are known to be strong triggers for killers of von Einem’s bent.

His mind starts ticking back, back to those days when the white ants ate the floorboards and he and his siblings rode around the suburban streets of Thebarton on pushbikes. Back, back to their Germanic father who terrorised the household, who bashed them, all the kids.

“He used to take me out to the back yard and thrash me with stinging nettles on my legs when I was a child. He was brutal. Distant and authoritarian.”

“How was he with Thora (von Einem’s mother)?”

“She was sick one day and he wanted her to get up, so he pulled her out of bed by her hair. But he never bashed her.” It is said matter-of-factly, as though this makes it acceptable.

“Oh, that’s awful. Paul described her as a saint.”

“Did he?” von Einem looks slightly flummoxed. “Look, yeah, she was a lovely woman. We were close but I wasn’t a mummy’s boy.”

I wonder why he feels the need to add that when the record stands for itself: moving with his mother from place to place after his parents separated, Bevan then in his 30s. Taking her to visit family, sitting with her eating cake and drinking tea from dainty cups at harpsichord meetings, driving her to church. Such a good, attentive son; such a loyal, lovely son about whom Thora’s friends in their Sunday best constantly remark that she is lucky to have him.

“What about you, Bevan? What is your story?”

He licks his lips and smiles. “I knew I was gay from when I was a child.” There is another memory he wants to share from that time. “My father had a drinking buddy who worked in the next building. I was on my pushbike in the main street where we lived. It was dusk, late afternoon, and he took me, he raped me right between the cars and a building. There were people around. I was about seven and I went straight home and told my parents.”

I bow my head as I listen to the story, shocked at how facile his recall is. “I told them and Dad said, ‘Come with me, son’ and he took me into the bathroom.”

I look up. “What did your father do? It was his friend who had raped you. What did he say?”

“He said, ‘wash your hands, son’.”

Bile rises in my throat, tart and pungent, but he doesn’t seem to notice my discomfort.

“Dad did nothing. He just kept drinking with him; never confronted him. Mum did nothing, either. She had to take Dad’s side. She had to turn a blind eye.”

The room is noiseless, save for the quiet rustling of the unarmed guards behind us, primed for any trouble. He is watching me for my reaction, moves in for his coup de grace. “The truth is, I enjoyed it.”

He wants to keep talking about rape; how he was abused by men two or three times when he was 16 years old.

“I asked them to stop because they were hurting me, but they wouldn’t stop.”

He is enjoying this. I asked them to stop because they were hurting me, but they wouldn’t stop. Just like you didn’t stop, when your victims begged you to. Just like you didn’t stop. He pauses, slightly.

“You’ve got no idea what it was like at home. They argued all the time and it just wouldn’t have been worth it for Mum to speak out. She had to say nothing.”

Try as he might to reinvent his childhood, this is not a picture of suburban normality; his mother seeking refuge in the arms of the Lord to escape her husband’s tyranny and his father cold and brutally violent.

His brain became hardwired during critical periods of his development – around seven, the age of reason – and his sexual behaviour set. At some point in that childhood he began to accept bizarre, extreme experiences as “normal”. It cannot be undone.

I shuffle the conversation sideways. “Did you come out to your parents?”

“No, I didn’t. I never told them. But Mum just knew anyway.”

This isn’t true, on Thora’s account, but the truth is clearly a slippery notion with von Einem. “You had a car accident when you were a teenager?”

He nods. “A car slammed in behind me, I went through the windscreen and got whiplash. There were no airbags in those days to stop you. Just my head went through.”

“Tell me about your friend, who the media call The Businessman?”

His face changes, the genial expression gone. He looks pained. “I haven’t seen him for years and years and years. He is worth two million dollars, but he hasn’t visited me or called me forever.”

I plunge on. “It has long been rumoured that he may be a member of The Family. Is he?” The question falls like a hard thud on the floor.

“I don’t know,” he says, looking directly at me. “I don’t know The Family because I was not involved with them.”

Denial. Flat, emotionless denial. Not a flicker, not a glimmer.

I return the stare. “Okay. Tell me what you do know about this man.”

He licks his lips again.

“He took me upstairs above where he works once and showed me a mattress on the floor. He told me that this is where he brings his boys.”

“What do you mean, ‘brings his boys’? To do what?”

“Well, you know …” A breath, a moment. He looks down to the floor and up again slowly; the cue that he is thinking. If this friend was involved in the murders and von Einem knows that, then he would have to admit his own involvement.

“He took them there to screw them. He was doing nothing else with them, as far as I know.” How slickly von Einem distances himself from the action.

His boys. I wonder how old they were. Our time is up. Von Einem stands to leave on demand from the guards, a habit learned from decades in prison.

“I’ll see you tomorrow,” I say as I stand myself.

He looks thrilled. “I didn’t know you were coming back!” He leaves me with a thought as I turn to go. “Do you know I’m likely to get a bashing when I get back to my cell? They’ll smash the door down and want to know who you were and what you were doing.”

I wonder why he’s lobbying this into the conversation now, before he returns to the cheerless routine of lockdown. I try not to look nonplussed. “Oh? They will?”

He nods, emphatically. “Yes. Very likely could happen.” And he is gone.

This is an edited extract taken from Banquet: The Untold Story of Adelaide’s Family Murders by Debi Marshall published by Vintage Australia, $34.99