Wine leader slams ‘anti-development’ lobby: Barossa is ‘asleep at the wheel’

Seppeltsfield owner Warren Randall, the man behind the so-called ‘Slug’ development, says the Barossa is falling behind other wine regions. Others, as you’d expect, strongly disagree.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

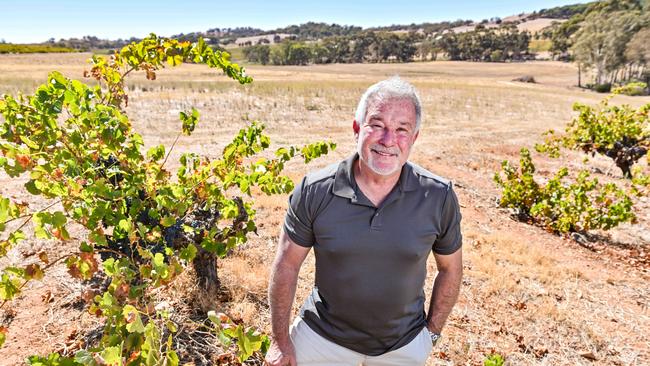

Robert O’Callaghan wants to make one thing clear. He is not anti-development. With a rising inflection to hammer home the point, the Barossa winemaking legend points to the growth of the region over the past 40 years and his own role in that story.

“The criticism we always hear is that we’re anti-development,’’ the founder of Rockford Wines says.

“We took a broken down wine region and turned it into a billion-dollar bloody asset, that’s hardly anti-development.’’

It’s true that in the mid-1980s, the state government was paying vineyard owners to pull their vines out of the ground, such was the pessimism about the prospects for the wine industry.

And it’s also the case that O’Callaghan was a key player in persuading many Barossa winemakers to keep their vines in the ground.

Now, four decades later, he says the Barossa is again under threat.

“It’s an international brand that takes you around the world. But for a whole lot of people, that’s just gobbledygook. They have no concept what brand integrity is,” he says.

Today, O’Callaghan is sitting in North Adelaide’s Wellington Hotel, along with his old friend and fellow Barossa heavyweight Robert Hill-Smith, whose family have owned Yalumba for generations.

The fact that both have agreed to speak to SA Weekend is an indication of how concerned they are about the future of the Barossa Valley. Hill-Smith is notoriously private and media shy, so his agreeing to talk about the future of the Barossa tells a tale in itself.

“This isn’t just about wine, this is about caring, about looking after a vision that’s worth preserving and enhancing not devaluing and cheapening,’’ Hill-Smith says.

“You’ve got this brand and intellectual property being created as a jewel in the wine world.”

This should not be allowed to be drained or diminished, he says.

TWO SIDES, ONE REGION

The debate about how the Barossa Valley should grow and develop is consuming the region. On one side, there are people such as O’Callaghan, Hill-Smith and Chateau Tanunda owner John Geber and the rejuvenated residents association, headed by James Lindner.

They use words such as “authenticity’’ and “landscape” and “culture’’ when talking about the Barossa.

On the other is Seppeltsfield owner Warren Randall, who sparked controversy with his $100m Oscar hotel development and developer Nick Paphitis who lost a Supreme Court case to Geber over his planned $25m hotel on the edge of Tanunda. They believe the Barossa is falling behind other wine regions, becoming stale and must do more to attract wealthy tourists to the region.

In the middle are the various councils that lay claim to a slice of the Barossa Valley and the businesses and residents who live there. Both sides of the debate are also claiming the majority of Barossa residents are on their side. Obviously, both can’t be right.

There is some common ground. Everyone agrees something must be done. There is general agreement that the Barossa needs more high-end accommodation. That it must attract more wealthy visitors to build on its reputation as a premium wine region.

It’s just that everyone’s GPS system is suggesting a different route to the same destination.

At the same time, the Barossa Council is predicting the population within its area will double to 50,000 by 2050, meaning there is going to be a need for more schools, hospitals, houses, better roads and public transport.

This month a new $40m upgrade of the Lyndoch footy oval was announced so it can host a Gather Round AFL match next year. It’s everything that comes with a rapidly expanding population, while at the same time trying to hang on to the traditions, landscapes and atmosphere that makes the Barossa so attractive in the first place.

The Barossa is also a vital economic contributor to the state. The SA Tourism Commission estimates the value of tourism was $326 million in 2022 and supported 1100 jobs. It’s a conundrum.

Warren Randall believes the Barossa is already slipping behind other wine regions, including McLaren Vale.

Randall has gone from hero to villain in some eyes. He was widely lauded for his transformation of the historic Seppeltsfield winery when he took it over in 2009. The plaudits were harder to find after he announced plans for a nearby 12-storey hotel development. The Oscar, or as it became known locally, the slug, which was subject to a campaign from a local residents’ association.

Barossa identities such as Maggie Beer and Margaret Lehmann were vociferous in their objection. The argument ended in the Environment and Resources Court, where Randall eventually prevailed.

Randall says the Oscar will be complete in about two years. Its estimated cost has doubled to $100m, but he says it’s exactly the kind of development the Barossa needs.

He says McLaren Vale, helped by The Cube at d’Arenberg, has “stolen 20 per cent’’ of the Barossa’s tourism. “You know, we’re asleep at the wheel,’’ he says.

Randall says he doesn’t have much time for the opinions of people such as O’Callaghan and Hill-Smith.

“There is a royalty, or they believe they are Barossa royalty, and look, they have a stance, they have an opinion, but it is anti-development,” he says.

“Most of that opinion is pinned by anti-development, it’s pinned by let’s keep the Barossa in the 20th century, perhaps even in the 19th century.’’

A gregarious character, who would never knowingly undersell himself, Randall is one of the biggest winery owners in Australia and says the idea for the Oscar was driven by a trip to South America.

In 2019, Seppeltsfield had come in at No.47 in a list of the world’s top 50 wineries. There were three from Australia on the list, the other two were Penfolds and d’Arenberg.

It was a good effort but Randall noticed that 15 of the top 50 were in Chile, Argentina or Uruguay and took himself off for a study tour – he went to all 15.

“The bottom line is all of them were out of this world, different, interesting, new architecture, not trying to copy anything old,’’ he says.

“And honestly, I was flying back thinking, ‘we are kidding ourselves in Australia, we really are’.’’

Out of that came the Oscar, and all the controversy that followed. Randall says he is unphased by all the criticism. He says he took even more flack when he redeveloped Seppeltsfield a decade ago and most ended up loving that.

“I’ve said to the Barossa, ‘Trust me, I got it right the first time, I’m going to get it right this time’.’’

He reckons he doesn’t even mind the “slug” nickname bestowed on it by unhappy locals.

“God loves all of earth’s animals,’’ he says laughing.

“And a slug is one of those animals.’’

The brief he gave to the architect was to design something “stunning’’ and referenced the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the Eiffel Tower, constructions which Randall notes were also controversial in their time.

“I think I always expected it to be polarising,’’ he says.

With the court case out the way, Randall says work has started preparing the site for the Oscar which will cost about $100m.

The earlier $50m estimate, Randall says, was for just the 72-room hotel. He says he may not even end up owning the hotel and is now looking for “top-class operators to lease it’’.

O’Callaghan’s view on the Oscar is that he “hates the bloody thing’’ but acknowledges at least it is being built in a tourism zone.

“So it’s not a question about building a hotel,’’ he says.

“It’s the style of the hotel and the impact that has, and again, it’s about the message it sends to the world about who we are.

“And it’s not who we are.’’

The need for a building to rival the d’Arenberg Cube has been rejected previously by another Barossa icon in Maggie Beer.

“Our icon is the whole of the valley,” she says.

“Not everyone travelling needs glitz and glamour. What they want is authenticity and realness.’’

A QUEST FOR BALANCE

James Lindner is spokesman for the Barossa Region Residents’ Association and was heavily involved in the battle against the Oscar.

He accepts that fight is over, but says the bigger picture of preserving the Barossa remains intact.

“That’s the thing it really comes down to. What is the vision for the Barossa? If you think of South Australia, and its global brands, the Barossa is probably one of a handful that actually reaches the world,’’ Lindner says.

“I think it’s a matter of finding a balance between what is old and what is new.

“And I think also, just understanding that the landscape itself has a value.

“So not just being able to build wherever you think you can.’’

One of the benefits of the Oscar, according to Lindner, is that at least it started people thinking about what the Barossa should look like.

Certainly, plenty of people have become experts in planning law and council boundaries in recent years.

There is a lot of unhappiness about changes to planning laws made by the last Liberal government that stripped appeal rights away from locals. The changes placed greater power in the hands of developers.

In April, 2020, new regulations came into force under then-state planning minister and Barossa MP Stephan Knoll, which made it easier for tourism accommodation to be built in regional areas if it was valued at more than $3m.

The new regulation meant projects previously classified as category three defaulted to category two – a category two development means only immediate neighbours can lodge an objection and have 14 days to do so and no appeal rights. A category three would mean anyone, anywhere in the state, could object and appeal rights are preserved.

Land use in the Barossa (as it is in McLaren Vale) is protected to some degree under the Character Preservation (Barossa Valley) 2012 Act.

It lists five “character values’’ of the region. The rural and natural landscape and visual amenity of the district; the heritage attributes of the district; the built form of the townships as they relate to the district; the viticultural, agricultural and associated industries of the district; the scenic and tourism attributes of the district.

But the decision as to whether to approve or not a particular development lies at local government level with an independent council assessment panel.

Barossa MP Ashton Hurn believes Knoll, her predecessor in the seat, went too far with his changes to the planning laws.

“I think that what we need to now do is look forward on how we can improve it for the local community,’’ Hurn says.

“And it’s not just the Barossa by the way, I think it’s right across South Australia.

“People want a say on what their own backyard looks like. And if the current system’s not doing that, well, we need to look at it.’’

The Oscar was approved by the Light Regional Council, as was another controversial development called the Paradigm in January.

The Paradigm has a curious history. Slated for a spot on the hill behind the St Michael Gnadenfrei Lutheran church at Marananga, the development originally called for a function centre, a cellar door and eight tourist cabins but was downgraded to two barrel halls that will store wine.

Although locals, going by the written responses to the project during the Light Regional Council’s consultation period, are worried the original proposal will be resurrected once the barrel halls have been built.

In one submission to the Council Assessment Panel, local resident Cathy Wills writes the proposed buildings are too big for the small piece of land and “have been positioned in an extremely prominent and elevated location above the State Heritage-listed Gnadenfrei Church. The size, colour and architecture significantly detract from the character and heritage of the area, which is cherished by the local residents and business community, and is an iconic landscape for tourists visiting the Barossa’’.

THE CASE FOR ONE COUNCIL

Lindner, along with O’Callaghan and Hill-Smith, believe one council should control what is known as the Barossa geographical indication (GI) and that appeal rights must be restored.

The GI is the official marker of what is the official Barossa wine zone as determined by Wine Australia.

Currently, the Barossa and Light councils are responsible for the majority of the GI, but Mid Murray and Gawler councils also have a small slice.

The main councils are at odds about a single Barossa council. Light mayor Bill O’Brien says the region will lose almost half of its rates revenue if it lost the Barossa section.

“It certainly wouldn’t be in the Light Council’s best interests at all,’’ he says.

“We would lose an extraordinary part of our council region and we’d almost become unsustainable.’’

But over in the Barossa Council, its mayor Michael Lange, known to everyone as Bim, says a single body that controlled planning and development decisions would be sensible.

“I’ve been speaking to my neighbouring mayors and the smart thing for us all to do is sit down and have a vision for what local government needs will look like, in the next 20-30 years because it won’t be the form that it is today,’’ Lange says.

“But some of the mayors I’ve talked to, they agreed with me, but say just not yet.

“We’re all territorial creatures.’’

The Barossa Council has released a draft growth and investment strategy document that is currently seeking community feedback. It looks at issues such as zoning, population growth, tourism, infill planning and projects such as the Concordia residential development which is forecast to add 10,000 homes and 25,000 people to the council area over the next 40 years.

At the same time, Lange says, the council must contain urban sprawl so the townships such as Tanunda, Nuriootpa and Angaston retain their individual character,

Lange has previously said he doubted whether his council would have approved Randall’s Oscar hotel, but then ran into his own trouble after permission was given to build a $25m hotel on the edge of Tanunda on land that was zoned as rural.

In 2021, the council gave developer Nick Paphitis permission to build a 141-room, $25m project on the edge of Tanunda.

However, a coalition of Chateau Tanunda owner John Geber, O’Callaghan and Hill-Smith funded a legal challenge which ended with Supreme Court Justice Malcolm Blue overturning the planning approval and stating the “proposed development was seriously at variance with the Code and it was legally unreasonable for the first respondent (Barossa council) to conclude otherwise’’.

But that doesn’t mean the project is dead. In its growth strategy, the Barossa Council is now proposing to rezone the same land from rural to tourist.

It’s a move that has provoked fury from Geber, who has plans for his own hotel within the Tanunda township.

Geber’s vision for the Barossa is based on the Napa Valley in the US, which tightly controls what development is possible.

“If you don’t protect your agricultural preserve like they did in Napa, you’re going to be gone,’’ Geber says.

He says the Barossa must capitalise on having some of the oldest vine stock in the world and the growing “own roots’’ movement which is producing some of the most expensive wines in the world out of France and the US, the region having avoided disease outbreaks that destroyed vines in other parts of the world.

“We’ve got I think, it’s beyond debate, the biggest resource of ancient vines on own roots of shiraz and grenache in the world, it’s a viticultural jewel,’’ he says.

Geber is so worried about development in the Barossa he has recently bought the land from a transport company that operated adjacent to Chateau Tanunda to prevent it being redeveloped into a residential zone.

Unsurprisingly, Paphitis, who has been selling real estate in the Barossa since 1974, has a different view and is happy the Barossa Council is considering reviewing the zoning status of his land.

“It’s interesting that every time we’ve made a submission for something that a minority seems to oppose us, or be difficult under the pretence of protecting the Barossa,’’ Paphitis says.

“The Barossa doesn’t need protection, especially from sensible and viable development.

“We’re going to remember that if this project had gone ahead, which this small minority oppose, there would have been 112 jobs in the Barossa.

“We had an interest from seven international and local companies at the resort to purchase it and this stopped dead.

“I think the Barossa has a special character. However, if you’ve been to Western Australia to the Margaret River, and you’ve been to the Hunter Valley and other places, in my opinion, they’re just as good.’’

There is concern that councils are too willing to approve any development that comes along. Figures provided by the Barossa Council showed of the 16 projects considered by its assessment panel (CAP) last year, 15 were granted planning consent.

The 16th was initially refused before consent was granted after the developer reduced its plan to build eight tourist units to six.

These are the projects considered to have a complexity that takes it out of normal council consideration – Light Council’s CAP approved all four projects that were submitted to it.

THE ROAD AHEAD

But the question remains. What happens next? There is no doubt that if the Barossa wants to extend its reputation as a premium wine district then it needs to build more accommodation, especially for high-end tourists.

There have been smaller developments, which people like Geber believe are more sympathetic.

Alkina Wines at Greenock is mentioned as an example of overseas money coming into the Barossa to create something new. Alkina is owned by Argentinian oil and gas billionaire Alejandro Bulgheroni who also has wineries in South America, Europe and in the Napa Valley.

Alkina was built in 2017, using the bones of the property’s farm buildings that date back to the 1850s.

Alkina’s managing director Amelia Nolan says she looked at other wine regions, including McLaren Vale and in Victoria, before settling on the Barossa.

“I always felt that there was this huge sense of food and wine embedded and woven into the community that was slightly different to other Australian regional experiences,’’ she says.

“It had a sort of old-world feeling about it, which I loved.’’

Alkina has a cellar door and two accommodation options, the homestead for $800 a night and the cottage at $475.

But Nolan agrees more up-market beds are needed to encourage visitors to stay longer and not just take day trips from Adelaide.

“You have to be able to accommodate them for one, two, three nights, so more money can be spent, and hence the Barossa prospers and moves forward,’’ she says.

Back at North Adelaide’s Wellington Hotel, Hill-Smith and O’Callaghan are also worried the current conditions of the wine industry could persuade some to chase short-term fixes at the expense of the long-term health of the industry.

The only recently lifted Chinese ban on Australian wine exports, an oversupply of grapes that has left some vineyard owners no choice but to let fruit rot on the ground, falling prices and changing drinking habits among younger people have all left the industry in a tough economic spot.

O’Callaghan would also like some form of a design code for the Barossa.

He says the Barossa is becoming a “shed central’’, with unsympathetic colours and off-the-shelf and industrial designs plonked around the landscape.

This question of the future of the Barossa will rumble on for some time yet.

For Randall, change is imperative. And needs to happen as soon as possible.

“The Barossa needs Oscar. It does. We are going backwards as a wine region in South Australia and Australia, and definitely the world,’’ Randall says.

For O’Callaghan, the battle is existential.

“There can’t be another Barossa. You can’t have another one if you kill this one. There’s no more of them.’’ ■