Author and doctor Peter Goldsworthy thought he maybe deserved cancer

When author and doctor Peter Goldsworthy was diagnosed with cancer he thought he deserved it. Then he felt strangely excited.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Peter Goldsworthy trained and worked as a doctor for 40 years but the first thing he did when diagnosed with the deadly blood cancer myeloma was to blame himself.

He was initially in denial because he refused to believe he had been diagnosed from an MRI of a dodgy knee.

A myeloma diagnosis typically followed an investigatory procedure involving the removal of bone marrow which is examined under a microscope. Yet here was his friendly radiologist saying the knee was in trouble but also that his bone marrow looked odd and it could be multiple myeloma.

He withheld the news from his wife, Lisa, while he mulled over the possibilities. Oddly, he was not entirely dreading a diagnosis that strikes fear into the heart of most people.

Goldsworthy is the well-known writer of novels, poems and stage plays, and cancer would present an abundance of new and interesting material.

“Either I get a clean bill of health, a priceless gift in itself, or I get a new wealth of experience, a journey beyond imagining,” he writes in The Cancer Finishing School. “Part of me will be disappointed if I haven’t got cancer, the part that half-hopes it is a gift …”

Having been told he was about to get what he half welcomed – a dance with death with an unknown ending – Goldsworthy felt strangely excited in a complicated way that he still finds difficult to comprehend. He knew it was a serious disease and he also knew people who had died from it, including one, a former patient whose diagnosis he had initially missed.

And yet.

“There was this weird excitement, ‘Gee, what a journey this would be if I’ve got cancer’,” he admits.

Once the diagnosis was confirmed and denial was no longer an option, the magical thinking kicked in.

Knowing all that Goldsworthy does about diseases and their causes, he decided he had cancer of the bone marrow because he deserved it. “It was the first thing that popped into my head because at some level we are all magical thinkers when our backs are against the wall,” says Goldsworthy, 72.

He is an atheist who lapsed and prayed to God when his son, Daniel, was dangerously ill in a London hospital, bleeding from his lungs and not expected to last the night. “Please, God, save him. Please,” he prayed to a God he did not believe in. Daniel survived, but because of good medical care, not divine intervention.

Now Goldsworthy was invoking wheel-of-life karma, the Buddhist concept that loosely means an action leading to future consequences. In Goldsworthy’s case, he concluded his cancer was karmic retribution for something he had done or not done. Either way, his past was catching up with him.

“I never believed there was any mystical connection in that karma – but there is a secular karma there that meant maybe I deserved something,” he says.

Even if it wasn’t a traceable karmic link, Goldsworthy thought he probably deserved to get cancer anyway. One line of guilt connected to a former patient, Hedley, who he had failed to diagnose with exactly the same illness. He felt it more than oddly coincidental that the one serious diagnosis he missed was the disease he now had. Obviously, he was being punished, he reasoned.

In his book, Goldsworthy says he always prided himself on being a near-faultless diagnostician and yet he had missed the telling symptoms of anaemia and bone pain in Hedley until the illness was well advanced.

Hedley was treated and lived until 90 but Goldsworthy wondered how many more years Hedley might have had if myeloma was diagnosed sooner.

“I couldn’t have dreamt up the plot for a novel, nor would I believe it in another’s: doctor misdiagnoses cancer in a patient, 10 years later doctor gets the same cancer,” he writes. “A metastasis for a metastasis. Capital punishment for a capital offence.”

On the plus side medically speaking, Goldsworthy was diagnosed early and he was younger and fitter; the dodgy knee was caused by too much bike riding.

He had patients with the same disease who were doing well in the care of specialist haematologist Dr Noemi Horvath at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. On the other hand, he had a good friend, Deb, who went through the same treatment and died two years earlier.

After convincing himself, finally, that the diagnosis was blind chance – if it was meant to be just deserts, he would have been diagnosed later, he told himself – he contacted Horvath because if anyone could save him, she could.

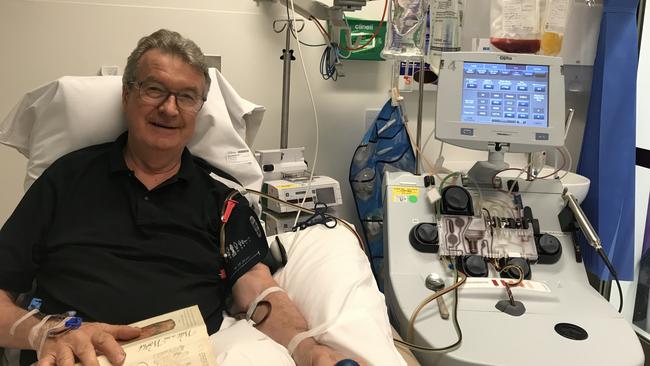

After failing to get a time frame for his death at their first meeting – “it’s way too early to think of that, Peter,” she told him – Goldsworthy began chemotherapy in the lead up to an autologous stem cell transplant that would harvest, then regraft his own stem cells.

The transplant would be potentially lifesaving but it was also a gruelling treatment that had to first wipe out Goldsworthy’s immunity. This meant physical debilitation plus a potentially fatal vulnerability to infections. He would be at home, in isolation, for months.

A glimpse of looming mortality triggers for many people an evaluation of their life. In Goldsworthy’s case, he felt drawn into a reckoning with his career in medicine, most of it spent as a GP. Part of looking back was to make his novel more interesting but he also had a sense of being called to account for the way he had treated people who came to him when they were sick.

“I think a diagnosis does that to everyone, we go back over our lives in the middle of the night when you’re not sleeping because of the drugs or whatever, it just pops up,” he says.

“A lot of it is just plain embarrassment, and then there’s the story about Hedley who had myeloma and it took me a while to diagnose.”

His embarrassments were few but they still made him squirm. In his first qualified year out, working as a locum in a suburban practice, he had to patch up a three year old with a fractured shin bone. He set it all up, took pride in his handiwork as he carefully moulded the plaster, and handed him back to his mother. Not long after, she was back. It was the wrong leg.

“I never made that mistake again.

“It haunted me for some time, but in the end, it also made a good story, a funny story,” he writes. “Which doesn’t quite explain why I have started squirming again, writing about it here, decades later.”

Harder in some ways to come to terms with were the patients whose death certificates Goldsworthy had signed, and who he had totally forgotten. It brought a pang of guilt and sadness to realise he did not remember them.

There was never any question that Goldsworthy would turn his cancer into a book and he began keeping a journal. He had been an occasional diarist over the years but says they were like New Year’s resolutions and lasted only a few days.

This time, he ploughed on and ended up with a sprawling mass of material that had to be condensed into a medical memoir people would want to read.

Cancer novels are a dime a dozen, he says, so the challenge was to make it new and different.

It might be a crowded field, but he was not deterred. Goldsworthy is not a doctor first and a writer on the side; he is both at once and remembers feeling impatient at the end of a day at the clinic because he just wanted to get home and write. In the face of a potentially fatal diagnosis, of course he would write about what happened. He also knew it would not be a breathless, emotional account of a life and death journey but more of a jokesy appraisal of a brush with death from a perspective ripe with black humour.

“I’m a writer, that’s what I do, I couldn’t stop myself if I tried,” he says.

The book goes through the painful early steps that began with telling family, which was made all the more complicated because his accomplished daughter Anna, a talented pianist and well-known author, was away at the Melbourne Writers Festival.

It meant telling his two other children and having to swear them to secrecy until he could sit down with Anna.

The dreaded ritual of the shaven head was short-circuited by Daniel who offered to spare Goldsworthy a visit to the barber and do it himself. There was chocolate cake and Champagne and the grandchildren watched as Daniel first gave his father a mullet, then a mohawk, then shaved him down to the bony-headed chemo look. Along the way, and before he started the most serious treatment, another friend died of myeloma. Actor Paul Blackwell pulled out of an interstate play after his illness recurred. His plan was to recommence chemotherapy and ward it off once again. Two months later, Blackwell was gone.

“It’s that sudden. And suddenly lasts forever. A shocking erasure,” Goldsworthy writes.

He approached treatment as an eventual rebirth as his bone marrow and blood cells were poisoned and destroyed, then replaced with his frozen stem cells that slowly attained new immunity, without the cancer problem.

The book does not dwell darkly on the treatment which is gruesome and debilitating and in which appetites of all kind, including for life, can disappear.

A roster of friends and family become his volunteer carers and included Adelaide’s Nobel prize winner for literature, John Coetzee, who Goldsworthy found downstairs asleep on his sofa. Another friend arrived from Wallaroo with fresh crabs and a six pack.

It was surprisingly easy to eat nothing, Goldsworthy writes, and even drinking water felt hard. “Food was like non-food,” he says. “It didn’t taste awful; I just wasn’t interested. It was an immense chore to put food in your mouth.” He lost 10kg and had a setback with an infection and says he had it worse than some people and not as bad as others.

Four years later, he is well and truly alive, back to bike riding and working as a GP.

He was slightly annoyed early on when Horvath reminded him myeloma was not a curable disease but he is living the truth of it.

He is in complete remission but on regular infusions of a maintenance drug. If it fails there will be another one, and hopefully one after that. “I think there are more drugs coming down the pipeline and when one of them stops working, they put you on a more expensive one,” he says. “So, I’m not too worried. We’re going to travel this year – I can take a month between infusions.

“How lucky to be in this country?”

Luck and joy, the blessings of love and family and the pleasures of being back among his patients are what matters now.

He is working three mornings a week, more than that and he gets too tired, but he never realised before quite how much his work as a doctor meant to him.

He says, in all seriousness, that cancer was a gift and he was lucky to have it.

“It is a gift in the sense of really understanding myself and understanding others who have been through the same treatment,” he says.

Whereas most people become obsessed with anxiety and fear about what might lie ahead,

Goldsworthy welcomed the intensity of the experience and what he could wring out of it.

“With me, I knew the obsession would be exploring the whole world of cancer and trying to figure out how I was travelling with it, how I could write about it and write it into submission maybe,” he says.

“Joke it into submission.”

He has ended up following a well-trodden path; grateful to be alive, not taking life for granted and being thankful for every day.

He was reborn with fresher eyes and says he became more sentimental writing the book and ended up with realisations that may sound like platitudes but which for him have acquired deeper meaning.

So far, the rebirth of his immunity – which required him to be vaccinated against all the childhood diseases – and his celebratory approach to the wonders of life have not worn off, nor do they seem likely to.

He has counted his blessings along with his failings and realised more fully how much the love of friends and family means.

“I always paid lip service to how complex and fascinating (life) is, but it is truly wondrous and it’s just beautiful to appreciate the little things,” he says.

“There is an extra intensity in going for a ride, the grandkids coming around, to films and the infinity of music.”