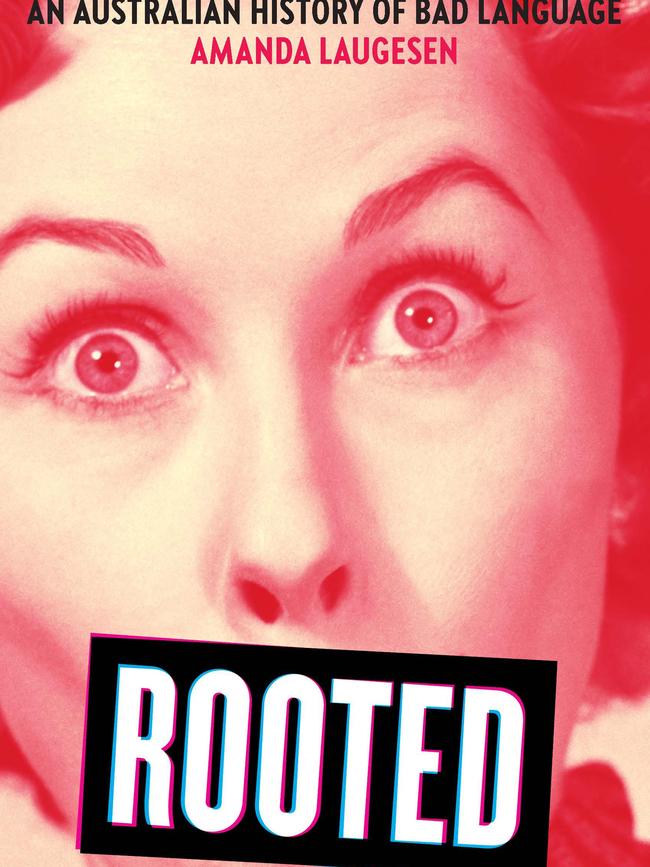

From The Bachelor to Barry McKenzie: Amanda Laugesen’s book ‘Rooted, and the surprise words invented Down Under

The c-word is losing its taboo but some expressions are strictly off-limits, says a new history of Australian bad language.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For someone who as a kid chastised her mum for swearing, Amanda Laugesen has come a long way. She’s now abso-bloody-lutely an expert on all kinds of bad language whose favourite 20th century swearword is … can we say that here?

Well, fine: she has, after all, just written a book on the subject – Rooted, An Australian History of Bad Language – so she qualifies as an expert. It’s f..kwit, although she spells it without the dots.

One of the attractions is that it is an Australian invention, with the first recorded use in Alex Buzo’s 1969 play Front Room Boys … “Ooh, temper! Well, ta-ta for now, f..kwit”.

Laugesen, a historian, lexicographer and director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre at the ANU, says the word was picked up by writers like David Williamson and Frank Moorehouse, whose contribution in 1980 was: “The present government consists of the finest set of f..kwits seen since federation”.

He might get an argument about that. But the embrace of the word, now spread to the world, shows the way that language, including bad language, is always evolving.

Laugesen knows a lot of bad words, and she wants to share them – but she’s never been a frequent swearer. In convent school, she says she learned that swearing wasn’t to be tolerated – a lesson she turned on her Danish mother, who ended up saying sherbet a lot, instead of the alternative.

“She enjoyed swearing,” Laugesen recalls. “She could get very cranky.” But for a long time, perhaps as an anti-rebellion, her daughter did not. “Everybody did, so I didn’t,” she says. But ultimately, it was a case of: if you can’t beat them, join them.

All of which underlines the power of some of these words, and the complexity of our reaction to them. Swearing doesn’t seem to be related to your education. It can come from different parts of your brain, depending on whether it’s spontaneous or calculated. Teenagers generally do it more than older people.

Why do it at all? “The research suggests most of our swearing is emotional, it’s cathartic,” Laugesen says. “When we hit our thumb or get angry we express ourselves through swearing.” And yes, studies show swearing can help you endure pain longer.

The bulk of our swearing is f..k and shit, studies suggest. But we use them differently depending on the context, she adds. It may be for humour, as an act of resistance to power, as abuse, to signal membership of a group, or just for emphasis. Think of the f-word’s versatility, she says, from anger, to dismay, to disappointment and as an intensifier as an adjective.

The use of swear words is also a way of wielding power in society, Laugesen says. It tends to reinforce the masculine perspective, and men are more likely to use the stronger words, while women who do that tend to be judged. Women and Indigenous people have historically been more likely to be punished for swearing, she says.

“This was a big theme of the book – who has the power to swear and then the power to condemn certain people or groups when they do swear,” she says.

In the 1960s and 70s women’s liberationists like Germaine Greer challenged the idea only men could use words like f..k and c..t, using them as a “form of subversion and resistance to power”.

But the libbers were condemned for it, one venting angrily that she’d been told by a man that “feminists would be taken more seriously if they didn’t swear”. Even today, Laugesen says, “women who use those words in public can be condemned.”

“This is a recurring theme in the history of swearing: that across time women have been repeatedly expected to ‘behave themselves’ including not swearing, and are reprimanded and punished if they do so,” she says. Swearing is about many things – but part of it is keeping women in their place.

The words themselves vary from country to country. Some of the favourite expletives in America are not as important here. Laugesen says f..kwit has been exported, but another homegrown word, rooted, wouldn’t travel as well. Rooted is linked to a slang term for penis and dates from around the 1950s, and also provides a nice double entendre for the title of the book.

Historically, the Aussie favourites have been the four Bs – bloody, bullshit, bastard and bugger, she says. They’re so widely used that Bob Hawke as prime minister once called a Whyalla pensioner on the campaign trail a “silly old bugger” while the defunct Australian Democrats’ call to arms was “keep the bastards honest”.

Does that mean we’re international gold medallists in the swearing stakes? No, says Laugesen, who thinks the idea that we’re a nation of great swearers – which many of us have embraced – is a myth partly created by what visiting Brits wrote about their experience of the colonies in the 19th century.

“The word bloody is a favourite oath in that country,” wrote Alexander Marjoribanks, in his 1847 book Travels in New South Wales, of what he called the Great Australian Adjective. “One man will tell you that he married a bloody young wife, another, a bloody old one, and a bushranger will call out, ‘stop or I’ll blow your bloody brains out’.”

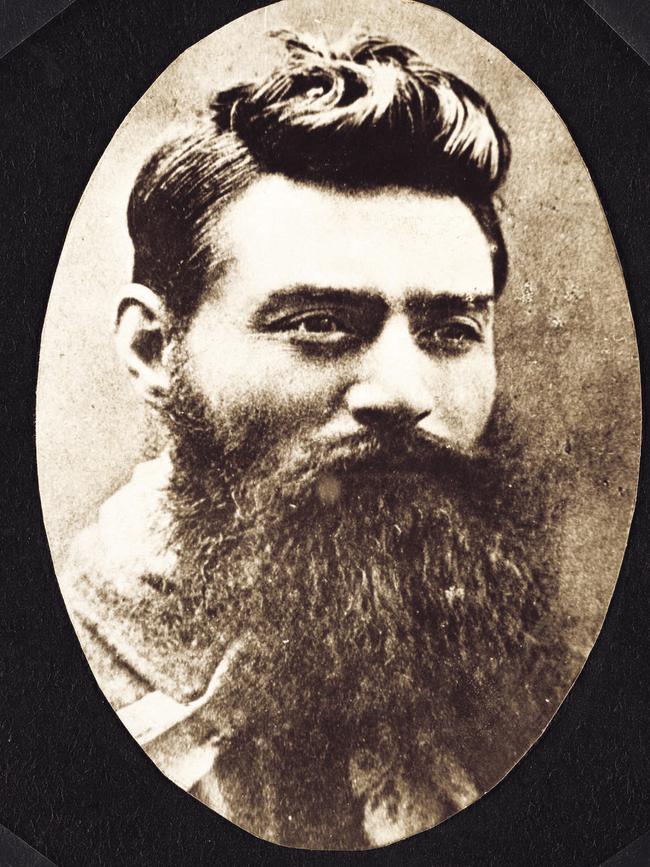

There was, apparently, so much swearing that “the Australian language” was used as a euphemism for the colonies’ penchant for profanity. The bushman, the bullock driver, the shearer, the bushranger – all of these were noted for their swearing abilities.

In reality, Laugesen thinks it was not that people swore more than they did in Britain, just that they were heard more. “You’ve got smaller groups of people, and people living side-by-side of different classes,” she says. “And you probably would have heard it a fair bit more than you might have if you were living in a particular part of London. But I think perhaps there is some truth to the fact we are more relaxed around bad language.”

Australians have been inventive with swearing (see list). Alex Buzo not only first used f..kwit but deadshit. Barry Humphries, while he didn’t usually play with actual swearwords, coined or helped make popular a host of slang phrases that have gone into the national lexicon, thanks to his work on films like The Adventures of Barry McKenzie in the 1970s. Think “point Percy at the porcelain”, “sink the sausage”, “one-eyed trouser snake”, and “bang like an outhouse door”.

But what exactly is bad language? Laugesen says that depends on society’s preoccupations at the time. When Western society was more religious, and damnation a widespread fear, anything blasphemous was powerful swearing.

Queen Elizabeth I, a noted exponent, liked expressions such as “God’s wounds!” – a reference to Christ’s injuries on the cross, which to limit offence subsequently became “zounds”. Polite euphemisms like that continued (darn, fudge, gosh) and Australians still embrace a few homegrown ones such as crikey, for Christ, and strewth, for God’s truth.

Body parts and functions were less of an issue until the Victorians arrived, and straitlaced attitudes were carried into the middle of the 20th century, when c..t and f..k started to become more widely used.

Today, Laugesen says, the c-word has become increasingly common. It is more frequently heard on TV or in film and among younger people. In the new movie The Gentlemen, for example, it features around 25 times with a couple of captioned references on screen as well (there are also about 150 f..ks in the script).

The word itself is found in place names in the 13th century and “does not appear to be particularly taboo until the obscene (the sexual and excretory) began to overtake religious oaths as the most reviled bad language,” she writes.

The first use of it as a promiscuous woman dates from the 17th century and from the 1860s is recorded as a term of abuse for a man. While it started to see increased use in the second half of the 20th century, it retains some shock value to this day although that power appears to be waning as it figures more often in film, TV and conversation.

“The ‘c-word’, of all swear words, remains taboo for some, but … is rapidly becoming an ‘everyday’ swear word for many of the younger generation, if perhaps still used more by men talking to other men than by women,” Laugesen writes.

She points to shows like The Bachelor and Married At First Sight as helping to normalise the word, even as they sought to gain notoriety for its bleeped-out use. She cites a 2019 episode of MAFS when one man described his female partner as a c..t for her changeable behaviour.

“I’m not calling her a c..t,” he clarified. “I’m saying she acted like a c..t.” He was reprimanded, says Laugesen, by one of the show’s experts.

On social media, most supported the man’s characterisation.

“Overall,” Laugesen writes, “few people expressed great concern about the word itself, or in this case even the context in which it was used – by a man of a woman, in an arguably abusive, certainly insulting, manner …”.

On The Bachelor that year, one woman, Monique Morley accused the bachelor Matt Agnew of being a dogc..t for kissing another woman. The elaboration on the c-word with dog, signalling betrayal, was an Australianism, Laugesen says. Like the MAFS case, it was widely discussed on social media to the extent that Laugesen thinks it demonstrates that the c-word has “arguably made it as a mainstream swear word.” So much so, perhaps, that it is also spawning other new swearwords, such as shitc..t, used to describe “the worst kind of person”.

Does that mean the c-word is losing its power to the extent it needs some bolstering? She hasn’t considered this, but does think it is becoming more common “so people are being creative with it”.

What is clear is that these traditional swearwords are not as offensive today as some discriminatory and racial words. Sometimes they are not even mentioned in stories about them.

Just how inflammatory one slur has become was demonstrated in recent British media reports about the change to a memorial for the World War II bomber squadron known as the Dambusters.

A stone commemorating the grave of the squadron leader’s dog, which died the night of the raid, and whose name was a codename for success in the operation, was removed. It was replaced with one not naming the dog, whose name was the slur. Most reports did not give the dog’s name, however some noted that The Dam Busters movie was often dubbed to give the animal’s name as Trigger. The removal of the stone, now in storage, was opposed by some as rewriting history but the RAF said it to be not in keeping with its values.

Laugesen does use the word in the book but says it has “become incredibly taboo and rightly so”.

Despite the more common use of the c-word, she is not convinced we will move to an “anything goes” approach on swearing. One of the risks in that is that people forget that the words can be used as abuse.

She adds that the history of our swearing has been intertwined with what it means to be Australian, although too often along white, masculine lines. Think of the 1960s books and film They’re a Weird Mob, the ockerish Barry McKenzie films, and David Williamson’s Don’s Party that same decade.

“If Australians are to be associated with bad language,” Laugesen says, “we might want to think about what that says – and what we want it to say – about our values and identity.”

Rooted, An Australian History of Bad Language by Amanda Laugesen (Newsouth, $32.99).

SOME AUSSIE ORIGINAL

SWEAR WORDS

F..kwit : First used in 1969 in Alex Buzo’s play Front Room Boys

Rooted: 1940s-50s from root, a slang word for penis

Donger: First recorded 1962, popularised by Barry Humphries, as in “dry as a dead dingo’s donger”

Shit a brick : Appeared in a Barry McKenzie comic strip

Deadshit: Alex Buzo play Macquarie in 1971

Ratshit: First recorded in 1972 in King’s Cross Whisper magazine

Shitc..t: A truly terrible person, contemporary, cited in Australian Urban Dictionary