Artist Tsering Hannaford, Archibald finalist, reveals why she almost quit painting

Lauded for her self-portraits, six-time Archibald Prize finalist Tsering Hannaford reveals why she almost quit her career – and overcame her crisis of confidence. Hear this story as a podcast.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Three years ago Tsering Hannaford faced a crisis point – a crossroads – over the direction her life had taken. The young Adelaide artist and multiple finalist in the Archibald Prize for portraiture had begun to wonder if this was really the career she wanted.

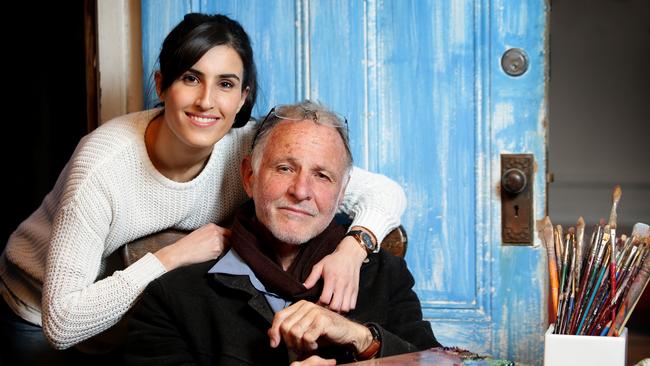

From the outside, her life seemed to be going brilliantly. The daughter of one of the nation’s most admired artists, Robert ‘Alfie’ Hannaford, she’d adopted his realist style and struck out on her own, managing what few achieved: making a living from art.

LISTEN TO THIS STORY AS A PODCAST

But inside the light-filled studio behind the West Hindmarsh home where her father once worked, there were doubts. Perhaps she should return to fashion design study, an early interest (not that she wanted to be a fashion designer). Or maybe go back to the University of Adelaide and follow up on her psychology major (not that she wanted to be a psychologist, either).

Some kind of 9-5 job with regular pay was starting to appeal. Creating art was dominating her life and causing stress. “I was just working so hard, and I wasn’t making much money, and it was difficult,” says the 34-year-old who has once again entered the Archibald, worth $100,000, with finalists announced next week. “So I started thinking of other sides of me, who were not just a painter.”

She wasn’t broke. She made enough to live and pay bills “but I didn’t know if it was worth how much of my life I devoted to it, meaning – no weekends, no downtime, no enjoyment of the small things in life. I was still able to support myself, but, you know, it was tight.”

What she wanted to know was whether painting was “just the result of a series of sliding door moments” or her true path. After all, she’d only taken the punt at the age of 24 thanks to a push from an entrepreneurial boyfriend.

Had she really chosen this life for herself? Metaphorically, she needed to take a long, hard look at herself in the mirror.

Fortunately, that was something she’d done with her art quite a lot.

Up at Alfie Hannaford’s home in the farmland around Riverton in the Mid North, there’s a big dam, perfect, if the rain’s arrived, for jumping into and swimming. Tsering (Tibetan for ‘long life’, and the name of a friend of her mum) loved being a kid on the farm. “Swinging into the dam was a favourite pastime,” she recalls. “There were hay bales stacked in the paddock next door, and you’d climb up, and … I had a treehouse and we had a pet sheep.”

Her mum, Shirley Andris was also an artist, spinning wool, dying yarn, and making shoes. And while her parents parted when she was four, the little girl easily moved between them.

Weekends often saw her at Riverton, where her dad had a big studio filled with his works. If she wasn’t outside playing, she says, she’d be happy in her own company. “I’d occupy myself for hours drawing.” She still has some of those early works, including one of a gang of monsters.

Her father noticed. She’d hang around with him in his studio and he recalls her being mesmerised by a Rubens print full of action, women, and wild-looking animals. “She did amazing drawings for a three-year-old,” he says. “They were full of life, none of this stick-figure stuff.” As she grew up, her parents encouraged her creative side whether through sewing and dressmaking, or art. In her studio today, she still has the French paint box that her father bought her for her 16th birthday.

“I just think he saw in me that it came so naturally, and I loved it,” Hannaford says. “And he could see, having had his career as a painter, what you can get out of life when you paint and draw. So he wanted to foster that, but he definitely never pushed me.”

There was another reason Alfie gave her the paints. Even if she didn’t want to be an artist, he felt the act of creation was good for her. She was sometimes downcast, like most teens, but always concentrated when she was drawing. Art “took her out of herself”, he says.

At school she was shy. Marryatville High was too big and the all-girls Annesley College was a better fit, although she had to be persuaded by a teacher in her final year to study art instead of chemistry.

“When I was at high school, I guess this is quite sad to say, I really feel like I absorbed the general attitude toward the arts that they’re not particularly valued as highly as the academic subjects,” she says. “I felt that if you went to art school, that means you couldn’t get into university to do a ‘proper’ degree. No-one ever said it; it was just the general attitude.”

There was also a sense that because art came easily to her, she didn’t rate it highly. The creative arts for a time did not seem like a real job. Did she not recognise she had talent? “I don’t think I valued it, that’s the long and short of it. It was just something I was good at.”

Hannaford couldn’t settle on a direction. She did do a “proper” arts degree at the University of Adelaide, majoring in psychology, but she also studied dressmaking at TAFE. But the pencils and brushes kept calling her, and she enrolled at the Adelaide Central School of Art, returned to university to complete a graduate diploma in art history, and volunteered at the art conservation centre Artlab.

It was when she was mulling moving to Melbourne to enrol in a master’s degree in conservation that she got a small shove. “I had a partner at the time who really saw that I was good at drawing and pushed me a little bit. And that’s what got me started on painting.”

She was 24, and had been enjoying selling dresses at a boutique in Rundle Street. But she felt she’d outgrown that life. The smiling, cheerful sales spiel and focus on looking great was starting to wear thin. Her more serious, introspective side questioned why she had to look a certain way.

“I really didn’t like having to wear make-up and I started to get a bit cynical,” she says. “So my first self-portrait I painted was the year I left that, and I’m looking incredibly sombre and serious and fed-up, and Dad encouraged me to enter it in the Archibald Prize.”

The prize, run by the Art Gallery of NSW, is high-profile, often controversial and a great opportunity for artists to showcase their talents. The first female winner was a South Australian, and daughter of a famous artist, Nora Heysen in 1938.

Hannaford’s self-portrait wasn’t a finalist, but was hung in the Salon des Refuses (the best of the rest) and Barry Humphries bought it for what the artist thought was an extortionate $6000 in 2012.

Since then her self-portraits have been finalists every year since 2015, except for 2019, when her painting of Adelaide’s Jasmin restaurant matriarch, Mrs Singh, made the finals. Last year Hannaford entered another self-portrait inspired by the 17th century Italian painter Artemisia Gentileschi, taught by her father and working at a time when painters were almost exclusively men. Gentileschi, one critic wrote, had turned the horrors of her own life – repression, injustice, rape – into brutal biblical paintings that were a war cry for oppressed women. She was also, Hannaford says, incredibly inventive.

Hannaford’s highly-commended picture finished as runner-up in 2020 to SA artist Vincent Namatjira’s winning portrait of ex-footballer Adam Goodes. “I didn’t see it coming,” she says. “Completely blindsided.”

This year she’s taken a different approach, entering a portrait of pioneering lawyer and judge Margaret Beazley, QC, who is now NSW Governor.

Her father had spotted her talents with self-portraits years before.

“As a teenager … she would often do a self-portrait when she was feeling bad. And they were wonderful. I’ve got one in my studio from when she was 12 or 13, and they were her.

“And that aspect did interest me. I thought to myself that when it came to portraits, when she did them in that mood … I realised then that she did have a talent for capturing the essence of things. So when she eventually took it up, I tried to encourage her.”

Hannaford agrees that creating her self-portrait has a psychological element.

“I find that process meditative and almost therapeutic,” she says. “I found myself drawing self-portraits in times of flux in my life. I’d maybe done three or four self-portrait drawings, from age nine to this first painting (that Humphries bought). I’ve still got them all. And I found it was quite cathartic to come home after a day in the boutique where I was happy and bubbly – very much one side of my personality – and then I’d come home and I’d do this portrait, and it was quiet and reflective and serious.

“And it was a bit of an antidote to a life that I felt didn’t quite suit who I was anymore. And that’s the power of painting your self-portrait for me. That’s the emotional element. The practical element would be that it’s good practice. You know, you sit there as long as you want. You don’t need to consider the time.” Nor do you need to flatter the sitter.

When I suggest her 2015 self-portrait, Objet Demode or ‘outdated object’, of her head as a bust seems “unforgiving”, she pushes back strongly.

The portrait – hair tightly pulled back, no make-up, no smile – reflects the reality that youthful beauty soon becomes a relic of the past, she says, but also her feelings of being objectified as a woman.

“Often people say, ‘Oh, you’re prettier than that’,” she says. “And I would challenge that because I do think in our culture if you’re a young woman, you’re expected to be a certain way and people, men, in my history have said, ‘Why don’t you smile?’ when I’m on the street, things like that.

“And I feel it’s a bit of an unspoken expectation that you look nice and that you are approachable and warm and friendly. And … sometimes you are. But that (the painting) is also me – that’s very real. And so it’s no less me than the smiling side.

“As a shy person, painting is the way that I can make a statement without needing to, say, verbally.

“So that’s kind of what my self portraits are. They’re a bit of a statement of the different perspective of my experience of my own life as a young woman growing up and having experiences, and then thinking about expectations and pressures.”

Then again, she is not too bothered by what people think. She can only paint for herself, and hope if the art is good, it will attract support. Her father’s advice has been never to worry about your reputation, only worry about the work.

“And that’s something I really admire about my dad, he’s never been about image, he’s really passionate about the art.”

She wasn’t completely naive about making a living as an artist. She took a business enterprise course, spoke with her father about his approach – and started painting, thinking that would be her job now.

Mostly self-taught with the help of courses in Adelaide, Paris and New York, she paints in the realist style, a more traditional approach. And while that has not been very popular for years with the Archibald judges, it is very much in demand for people who want their portrait painted.

So the business model has been to paint commissions – maybe a business leader, a university chancellor, school principal, or governor – to allow her to pursue her own choice of subjects, perhaps for exhibition or competition.

“And for a few years, it was all very exciting,” she says. “And then I got to the stage where my friends were starting to buy houses and I was realising that I needed to work twice as hard as everybody else just to get myself to that level, where I could have a sustainable career.

“Sadly, I think I got to a point where I realised I would either need to give it up or just increase my – not unnecessarily output, but focus.”

Painting required complete commitment, she learned. Talent only got you so far. Sacrificing her personal life was part of the deal. “It takes all of your emotional energy,” she says.

While she loves doing them, the portraits chew up time. No photographs here. One thing her father did advise her was to always work from life. She requires seven or eight days of sitting with the subject. Each day involves six 20-minute poses spread over three hours with breaks. The painting itself might take two or three weeks. The benefit is “you feel like you’re having a connection and making something real”.

With portraits, there’s also plenty of chance for conversation, and hearing people’s stories can help inform the painting. She always paints people as she sees them, and some like that and others feel uncomfortable. Halfway through, she asks the sitter about the unfolding image. If they want more animation, she’s happy to adjust it. “But I also like it when someone says, ‘just paint me as I am’.”

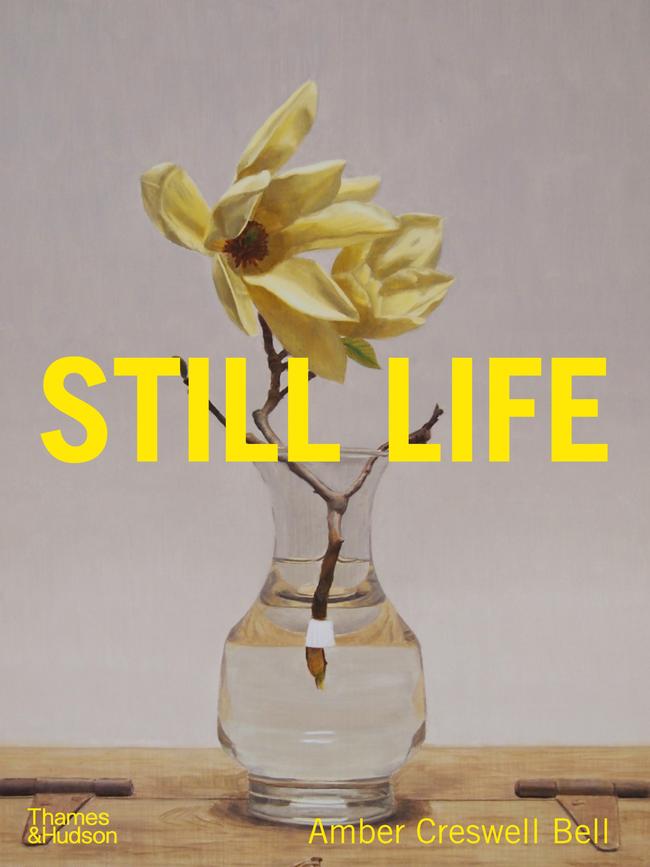

Her still-life work has also become noticed, and she especially loves magnolias – simple, elegant and ephemeral. A new book, Still Life (Thames & Hudson, $59.99), features one of her works on the cover. She tells author Amber Creswell Bell what she loves about still life is “creating a sense of order in life, if only on the canvas … a sense of tranquillity and calm”.

Hannaford is still young, but the Art Gallery of South Australia has an eye on her work. “She’s on our watch list,” says assistant director Dr Lisa Slade. “We don’t want to wait too long either.

“With Nora (Heysen) we acquired quite early, which was really great.

“I really think she’s a rarity – she has a clarity of purpose and exceptional skills. She uses realism with great virtuosity to describe herself and her world.”

Slade says Hannaford’s ability belies her age. “I’m astounded by her skill … her obvious kind of patience. But also, more importantly, her works – and this includes her self-portraits – are infused with extraordinary empathy.

“There’s a beautiful portrait of Mrs Singh. I think it is full of the most extraordinary humanist sensibility and empathy. You’re taken right into this moment of reflection and almost melancholy, I think, with the sitter. Tsering is not afraid to shed a little bit of shadow, not just allow them (the subject) to sit in the light.”

Hannaford’s self-portraits also show she isn’t afraid to share her own vulnerabilities, Slade adds. They are part of a history of women painting themselves – originally because they had no other choice of subject matter.

Only with the invention of mirrors could women paint from a live sitter – themselves – and even in the early 20th century British women art students were forbidden from painting from nude models.

Despite outside perceptions of her talent, inside the studio the demands of the work, weighed against uncertainty and the struggle to become financially secure, led to her crossroads moment three years ago. There were taxes and superannuation, basically 40 per cent of the sale price of a piece, the cost of materials, framing.

“I started to think it would be nice to be employed by someone and have the benefits, you know – sick leave, holiday pay, maternity leave in the future,” she says. “I started to realise I’d set myself up for a life where there were few safety nets. It was going to be a lot of hard work. It was all on me. And I was starting to think maybe it would be nice to work in a different profession and have painting as something that was just enjoyment.”

But she persevered – and raised her prices. She knows that makes her work less accessible, but says she has no choice. A portrait these days costs between $10-$20,000. A small still life can be had for around $2500 and up.

Hannaford says she’s now made her own choice for her future. She looked in the mirror and realised she did love painting. It offers a sense of challenge, freedom, and the adventure of travelling the country, she says. No week is ever the same, and if it is solitary at times, that suits her personality. She’s even expanding her market, and is now renting a Sydney studio.

Her father Alfie says he’s been encouraged by the way she’s come through her moment of doubt. “And what’s more, she’s doing unique work,” he says. “I mean, those still lifes, her own self is coming through in some of those paintings. She’s got a delicacy of touch that I didn’t know about. Now I see it in some of her work.”

He predicts she will continue to evolve as an artist. “It’s all a discovery – and the only way to do it is in your work.”