Anne Ruston: From Riverland rose grower to the minister for keeping Australia’s women safe

She starred in university drinking, never had a plan, and fell into politics. So how did Renmark’s Anne ‘Rusty’ Ruston become one of Australia’s most powerful women?

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Anne Ruston ponders the question: what do growing roses and politics have in common?

Well for one thing, notes the woman who once ran the nation’s biggest rose supplier in South Australia’s Riverland, there are plenty of pricks – of the thorny kind.

“There’s always pitfalls, whether it’s being pricked by a rose thorn or making a wrong decision,” she says. “And that’s why planning is always so important – so you put your gloves on.”

Ruston has donned the gloves again. As Minister for Women’s Safety, she’s co-ordinating a new national plan to tackle domestic violence, the abuse that, on average, kills one woman every nine days and traumatises thousands of others, and children, each year.

It’s a crucial task with plenty of potential for barbs. Governments can’t monitor what happens inside the nation’s homes, the SA senator says. More money and more ambition to drive domestic violence cases “towards zero” is vital but the key, she believes, is that attitudes must change.

“I want everyone to accept this is their problem, that’s my ultimate goal,” she says. “It’s not the government’s problem, it’s not the service providers’ problem, it’s everyone’s problem.”

But how do we know what may be happening behind our neighbours’ doors?

“We all have a role to play in challenging disrespect,” she says. “I encourage all Australians to talk about what respectful relationships look like and call out disrespectful behaviour. Don’t walk past it, don’t ignore it.”

For Ruston, “a country girl” from Renmark, pushing the case and demonstrating the Morrison Government is serious about women means stepping into the spotlight. That is something she has managed to largely avoid, despite since 2019 being the federal Minister for Families and Social Services with a portfolio that spends more than a third of the nation’s budget.

“I’ve never been somebody that’s sought the media spotlight for the sake of seeking it,” she says. “I understand now in my new role I have a very important message to deliver … women’s safety is topical for a whole heap of really horrible reasons. I will certainly increase my profile. It’s a super important message.”

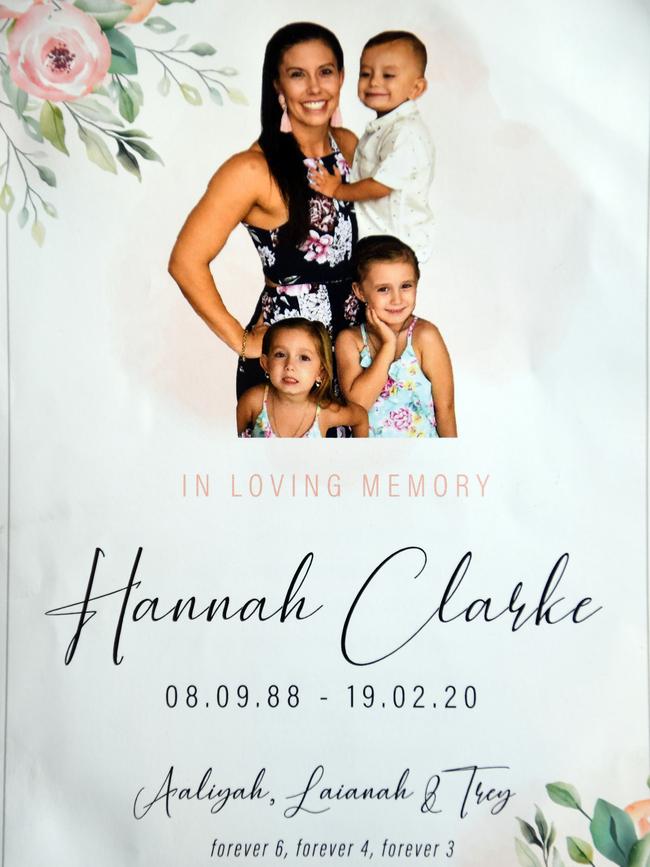

It was the murder of Hannah Clarke and her three children in Brisbane in February last year that Ruston says was the catalyst for a national cry for action. Clarke’s estranged husband, Rowan Baxter, lit petrol he’d poured over her and the car, in which the children sat trapped in their seat belts.

The murders galvanised demands for action, but over time the push broadened to anger about the wider treatment of women. Those concerns have been kept on the boil by a stream of front page stories focused on male behaviour including the resignation of the University of Adelaide vice-chancellor Peter Rathjen over sexual harassment findings, a determination that former High Court judge Dyson Heydon was a serial sexual harasser, and the alleged rape in Parliament House of former Liberal staffer Brittany Higgins.

Australian women are concerned about their broader treatment as well: a World Economic Forum report on women’s equality with men ranked Australia 50th in the world, down from 24 in 2014 – way behind New Zealand in the top five, and most OECD countries.

Scott Morrison, accused of being out of touch on women, in March elevated a number of female MPs and created a cabinet task force focused on women’s issues.

Ruston, 58, was a big winner. So big she’s slipped under the radar to become one of Australia’s most powerful women. She was given a new portfolio on women’s safety, joined cabinet’s 10-member leadership group, manages government business in the Senate, and was the only woman on the powerful expenditure review committee of cabinet, which set the budget.

Her portfolio, covering everything from JobSeeker to pensions, spends more than Defence – and hit close to 40 per cent of government outlays in 2020 thanks to the Covid cash rollout.

That’s a lot of responsibility – and, she insists, a complete accident. Not only did she never intend to be in politics, she had no career plan of any kind.

“If an opportunity goes past, give it a go,” Ruston says of her life philosophy. “If you don’t like it, you don’t have to stay there. So I’ve never ever planned anything.”

Her mum called her a lizard chaser. “She would say that if I was walking down a road and saw a lizard, I would chase the lizard rather than continuing down the road. “Even as a kid, as soon as something new and interesting came along I’d chase it. I think … this has meant I’m always willing to embrace new opportunities.”

It seems to have worked. She has gone from a Renmark fruit block and university student majoring in pub drinking to the top rank of Australian politics.

Now, after a budget that announced an extra $1bn on 16 new “women’s safety” programs she needs to do two things: help rescue perceptions the government handles gender issues badly, but, more importantly, bring about real change in tackling the violence against women and children she calls “a plague on Australian society”.

Disrespect is the key word. It may not lead to violence, but “all violence starts with disrespect,” Ruston says.

Her next big move will be a summit involving the states, territories and key interest groups to set a new national plan to end violence against women and children. It was scheduled for July but lockdowns have forced a delay until September, likely in Parliament House Canberra. The current plan, begun in 2010, expires next year.

THE EARLY DAYS

Ruston was raised in Renmark, on a soldier settlement block that her grandfather Cuthbert Ruston turned into fruit property irrigated by the waters of the River Murray.

Her father John was an engineer who fixed farm machinery and her mother Joy a nurse and midwife.

As a kid she was nicknamed Rusty – a moniker still favoured by her National Party colleagues in Canberra – and says she was a bit of wild teen.

She was no star student, but she was always up for something new.

“I think maybe I’ve always just given anything a go,” she says. “It’s probably the reason why I’ve had so many broken bones because, you know, somebody gave me a motorbike to ride or a horse to ride or, you know, gave me something to jump off.”

She left Renmark to study economics at Flinders University at 17 and didn’t expect to be back. While the only thing she passed with flying colours was “tavern drinking”, she later completed by correspondence a bachelor of business at the University of Southern Queensland.

“I think after having too much fun, I realised that maybe I did actually need to settle down,” she concedes.

One of Ruston’s first real jobs was as a secretary in the office of state Liberal MP Peter Arnold back in the Riverland. He was dictating a letter before he realised he’d employed a secretary who couldn’t type.

While she did not join the Liberal party until 2008, her rural perspective made her a perfect fit for conservative politics. She became an adviser to Liberal state minister Graham Ingerson in the mid-1990s before becoming chief executive of the National Wine Centre, where she stayed until 2002.

Then, with new baby Tom in arms, she saw another opportunity. Her uncle David Ruston, her father’s twin, had turned part of the family Renmark property into a major rose-growing operation. The dry climate was suited to the prized flowers and the availability of plenty of water meant Ruston’s Roses became the largest commercial rose grower in the country.

When David became ill in later life, he sought advice on selling the property. Single, he had no succession plan. Ruston went home to see if she could offer advice. “And we were driving back to Adelaide, and I was like, ‘Maybe we should buy it’.”

That was 2003. It proved to be tough timing. The roses needed a lot of water to bloom, and had been using 150 megalitres a year. But the millennium drought slashed the property’s water allocation, and despite replacing flood irrigation with drippers, Ruston and her husband had to cut to just enough to keep the roses alive. They diversified the operation into a tourist attraction with a cafe and retail outlet.

ENTERING POLITICS

Her ascent to Canberra began when she was campaign manager for Tim Whetstone in his battle for the seat of Chaffey, which includes Renmark, in 2010.

“I never intended to go into politics. That was never my life’s ambition. In fact, that was the last thing I ever considered,” Ruston says. “And it just happened to be like a weird set of circumstances conspired.

“I campaign managed Tim Whetstone when … we weren’t expected to win because we needed a 16 per cent swing and we got like a 22 percent swing. And so all of a sudden the Liberal party was, ‘Oh my gosh, that was pretty impressive’.”

She was vice-president of the state Liberals in 2011, and in 2012 replaced Mary Jo Fisher who resigned her position in the Senate after allegations of shoplifting.

The only thing that gave Ruston pause for thought was that her son was so young, but in the end she went. “I was intrigued to see what it was all about … what it would be like to be the person making the decisions, who actually had the capacity to make change,” she says.

Her maiden speech set out her country credentials with a “strong emphasis on independence … honest hard work and the rewards that it brings, on personal responsibility for your decisions and your actions, and on a practical approach to life, family and work”.

While many believe she aligns with the Liberal party’s moderates, in fact she holds conservative values. And no, she does not support quotas to increase the number of Liberal women MPs. It is, she says, “too blunt an instrument”.

Two of those who’ve influenced her most, she says, are the conservative ex-Finance Minister Mathias Cormann, for his work ethic and what she says was a lens of fairness and equity, and his replacement, the moderate SA senator Simon Birmingham, who now has Cormann’s job.

The way Ruston sees it, the empowering qualities of taking personal responsibility for your actions fits with her key challenge: reducing domestic violence by fostering a change of thinking in Australian society about how we behave towards each other.

It’s unrealistic, she argues, to expect government to legislate to fix social problems. “We can provide leadership, we can provide that continuity and consistency across measures, we can put things in place that encourage people to go down a particular pathway, and put laws in place to punish people for wrongdoing,” she says.

“But that won’t change people’s attitudes towards domestic violence. The only way … is if the community actually accepts the fact that we’ve all got a role to play in the solution. Because unless you think you’re part of the problem, you’ll never be part of the solution.”

Just how big the problem is got an airing on radio earlier this year during a “lying” game hosted by Kyle Sandilands and Jackie ‘O’ Henderson when callers tell lies to earn money. In this case “Jess” fibbed to her partner “Jake” that she had damaged his motorbikes. His on-air response was to abuse her, calling her stupid, an “object”, and warning her he was coming home and she’d better have packed her bags.

“And it actually was all brought home to me in this one segment,” says Ruston. “Everything that we’re trying to say around respect. Sure you can be cross – I have no problem. People get cross all the time. But in being cross, how are you calling somebody an object?”

Respect is not only an issue for men, she says. “Domestic violence is overwhelmingly perpetrated by men against women,” she says. “But I think the idea of respect and respectful behaviour is a responsibility for everybody, men and women.

“I think if you want to stamp out domestic violence, you’ve got to establish respect, and respect is not something that only men have to embrace.”

MOVING THE DIAL

One of the most urgent challenges is establishing whether progress is being made.

“It’s a plague on our society that we should have domestic violence rates at the level we do,” she says. But, she adds, we have a lack of measurable data on whether inroads are being made.

Still, she thinks “we have moved the dial in some respects”. While the numbers are high, it is “missing the point” to judge improvement on the level of incidents because when the first plan was put in place almost 12 years ago, domestic violence wasn’t so widely discussed. Low levels of reporting didn’t reflect the reality.

Several campaigns since then aimed to educate the public about what disrespectful behaviours – potentially precursors to violence – look and sound like; encourage those behaviours to be called out; and provide the tools to help people escape violent situations.

“So I think the increase in the incidence of reporting of domestic violence has been because we brought it out of the dark and into the open,” Ruston says.

But that is no longer an explanation. “That’s why I think it comes back to behavioural change.”

One of the targets for change is children. “The thing we now need to do is make sure we stop these behaviours in the first place,” she says. Teachers, coaches, and people with influence need to call out disrespectful behaviour when kids exhibit it.

So how do you make women safe? The next phase needs to be more ambitious, she says. “I think we need to move from informing and getting people to understand the problem to actual action.” The extra $1bn the government says it will spend on the issue over four years needs to go into both ends of the problem.

To help women to leave a dangerous relationship, “we need to make sure we have got the resources there to be able to support them through the process, not just of leaving, but getting on with their lives independently”.

There’s a new payment of cash and kind worth $5000 to help up to 12,000 women find their way to a new life without having to go back to the perpetrator.

At the same time, better prevention and early intervention is needed to stop violence in the first place. One group stands out for attention on that front.

“We know that 60 per cent of people who are arrested in some sort of intervention in relation to domestic violence already have some sort of criminal or police record,” she says. So targeting perpetrators and trying to rehabilitate them is crucial, and $9m has been slotted for that.

As well, she’s helping fund the states and territories to share information better, not just to prevent perpetrators moving with impunity across the country, but to provide accurate statistics on the problem.

“The target (for domestic violence) must be zero, but the best thing that we can do is to get clarity around the data, so we can establish where we are, so that we can set ourselves goals and targets.” At present it is hard to know which services are working best and deserving more support.

“What we need to know is, are the police receiving more or less complaints? Are the hospitals seeing more or less presentations?” she says. To do so requires a national agreement to provide the data to a centralised platform, with consistent ways of measuring and no fear that some states will look worse than others, she believes.

“The other really big thing I’m keen to look at is the impact on domestic violence on children,” she says. While focus has been on the physical impacts, the mental aspects on kids is not well understood.

The role of technology, especially mobile phones, also needs more attention. “A telephone is probably one of the weapons of choice in relation to coercive control,” she says of the manipulative and intimidatory tactics many perpetrators wield in areas like finances to control their partners.

For example, where a perpetrator may need to make regular payments to their partner, perhaps for child support, they may use the transaction as a vehicle for abuse: Ruston says someone paying $200 a week could send 100 $2 transactions, each with a threatening or abusive message.

“These are the kinds of things that nobody even knew about 20 years ago,” she says.

“Physical violence is obviously the most horrific end of the spectrum, but there are a lot of other things. And often what we’ll find is that some of these other forms are a precursor to physical abuse.” Indeed some women feel the intimidation, driving fear and anxiety, can be worse than some forms of physical abuse.

The government is under pressure to do more on all fronts, although Labor’s spokeswoman Senator Jenny McAllister cancelled an interview for this piece. But even Liberals want more done.

A cross-party federal parliamentary committee earlier this year warned $3bn in spending over the past decade had done too little. Perpetrators needed to face tougher punishments, financial penalties for the cost of their behaviour, and a public register so women could know if their partner had a history of offending.

Ruston says nothing is off the table.

A fresh and more ambitious direction is needed, she says. Until now, a lot of the federal focus has been on increasing awareness and helping victims – now it’s time to direct more effort to reducing the violence.

“We’ve got to be the fence at the top of the cliff,” she says. “Not just the ambulance at the bottom.”

For domestic violence or sexual assault counselling call the national 1800 RESPECT hotline (1800 737 732). For help leaving an abusive relationship in SA: Domestic Violence Crisis Line 1800 800 098. Men who have anger, relationship or parenting concerns: Men’s Referral Service 1300 766 491 or Don’t Become That Man hotline 1300 24 34 13.