Ali Clarke: My tough, strange and emotional journey to learn about my birth father’s life

Adelaide radio star Ali Clarke is on a gruelling quest to uncover the true story of her long-lost birth father – and is discovering much more about her dad, her family … and herself.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is a cold and dull morning in Wellington Square, yet she is wearing sunglasses. We meet at a coffee shop but she doesn’t drink coffee. The maroon jumper of the Queensland state rugby league team pokes out from the ubiquitous Adelaide puffer jacket.

It seems to perfectly reflect the somewhat muddled life of Ali Clarke, 46. As if things weren’t hectic enough, she has just turned her world upside down, exposing an inner turmoil in a very public search for details of her long-lost birth father Philip Joseph McManus.

Step-by-step details of the saga are being played out on the Mix102.3 Ali Clarke Breakfast Show. On air, the search is being managed and the steps scripted.

Off air, as she describes the saga, and despite being a stranger, I feel I am witnessing the opposite. I’m hearing the real Clarke, without the commercial radio affectations essential for success in the medium.

This is raw and unscripted Ali Clarke. It’s the cool and confident Adelaide A-lister, but also the vulnerable, dedicated mother of three, self-made woman, well-educated university Honours graduate, and, more recently, temporarily lost soul.

When you hear the details of the troubled voyage surrounding her unknown father, the struggle is real and really traumatic. It is anything but romanticised or sugar-coated. In short summation, he drank, he partied, his wife and child walked out when Clarke was only one, and then he died.

And all this before she was 11 years old.

“I hate using the word journey because reality TV is somewhat busted. But it definitely has been. And it’s been a very strange one,’’ Clarke begins.

Stumbling into the search as she has, by circumstance more than design, Clarke doesn’t portray herself as the dutiful daughter seeking to help her father’s legacy live on.

“Up until a very short while ago, I hadn’t thought about this person at all,” she says.

“I hadn’t thought about that side of my family, apart from maybe glancingly. I just thought, ‘Oh, yeah, well this is part of my history’.”

There are two very good reasons for this apparent ambivalence.

Being birth-fatherless wasn’t the only trauma Clarke faced growing up in Brisbane in the 1970s and 1980s.

Her mother, Mary Carle, then in her 30s, struggled hard to pay the bills, working in the public service with her daughter in childcare from 8am until 6pm.

Stability was returned when she remarried, to Rod, now 75, but another family twist soon came, when brother Nick, now 40, was born with a severe intellectual disability.

In one of her many media columns in adult life, Clarke paid tribute to her mother’s ability to cope with the turmoil that followed. “Family members said to put him in a home, friends dropped away and you and dad (her stepfather) had to work through how to give me a life away from the awesome blessings, but tiring challenges, he can bring.”

Until this year, Clarke admits that, despite the turmoil, “I’ve never needed or looked for anything”.

“My brother came along when I was seven and living with his abilities, it was all hands on deck and that was just where our family was,” she says.

“Now, that doesn’t mean that I didn’t feel loved or connected or anything like that, but there weren’t the nightly family meals. With Nick’s disability, even when I’d go home – as it was and as it should and had to be – it was about his care. So our life was all about my brother, which it should be.

“So with that emotional energy, I didn’t really have time to think about anything else.”

Including the loss of her birth father.

“It was a very practical life with Nick, and mum never spoke about it or had time to,” Clarke explains.

“She also grew up in her generation, where you didn’t talk about those things like that. Her parents, who I was really close to, they never spoke about anything, not emotions or anything like that.

“So life was matter of fact; keep calm and carry on as such.”

Boarding school in Brisbane soon followed, in part for some respite from the daily family challenges, but further accentuating the dislocated family setting.

“I guess I moved out of home essentially when I was 12 years old,” Clarke says.

“I was a swimmer and had music and all that sort of stuff.

“And I think Nick’s behaviours were growing increasingly challenging, and so they wanted to give me some space so I could have that time.

“Although mum did say the other day that she went to boarding school and she wanted me to have the same experience.

“I think it was just more that idea of being able to let me have my own space to find out what I wanted to do and to be.”

Life moved on.

The missing parent figure had been replaced in the form of Clarke’s beloved stepfather – the second husband in her mother’s life, Rod.

The Phillip Joseph McManus chapter was quietly closed.

Until earlier this year.

Clarke was hosting a segment on her morning radio show that helped reconnect people with their birth families. She was listening to the stories when she felt a change come over her.

Later, her producer called when she wasn’t feeling well.

“I said, ‘you know, I feel like a fraud listening to these people’. And she said, ‘Well, what do you mean by that?’,” Clarke says.

“So I’ve been listening to these people trust us and trust me with their story and put themselves out there yet … yet I’ve got a story very similar, I told her.

“Then I told her my story and I guess in that moment, I knew that something would come of it, but on the proviso that Mum and Dad were okay with it.”

Dad, of course, being Rod.

“I call him my Dad, my stepdad, because speaking to them and making sure he was comfortable was the most important thing out of all of this,” she says.

“And his response was, ‘I think you’re mad if you don’t’.

Mary agreed. The timing was good. It felt right. So the search began.

It turned out Philip had remarried but there were no other children; Ali’s name was the only child’s name listed on the death certificate.

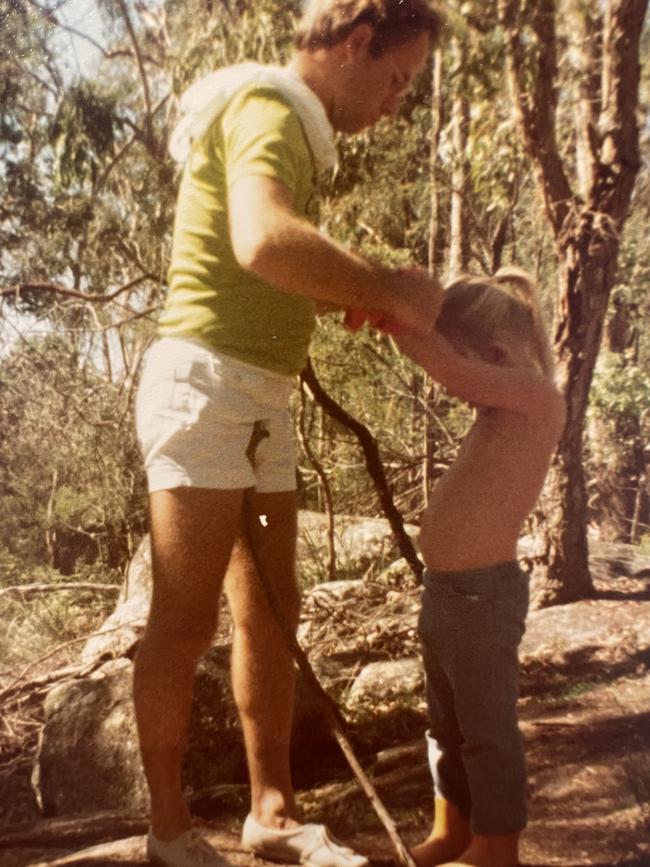

Philip and Mary had met in Canberra. He was working for the Overseas Telecommunications Commission, which was responsible for all the international telecommunications services throughout Australia. They moved around the country, landing in Darwin in 1974, where they confronted Cyclone Tracy. Ali was born two years later.

The couple would split while Ali was still a baby. Mary was 31 at the time and says she was forced to act in the best interests of her child.

“Yes, I think any break-up is particularly difficult in one way or the other,” Mary says now.

“Even though I instigated the break-up and walked out, Ali was my total focus and I needed to remove her from a terrible situation – exposed at a young age to alcohol and shift work, where her biological dad was not home a lot.”

Mary would attempt to reunite her daughter with her father in 1982, but it ultimately proved futile. He was apparently on an Antarctic research vessel at the time.

Clarke’s only contact with that side of the family thereafter was with her paternal grandmother in the UK, who sent regular and thoughtful presents.

Around the age of 11, Clarke would find out that Philip had died suddenly.

“I can vividly remember where I was sitting in our old house when mum came in and said, ‘Look, he’s passed away’,” she says, adding that Mary was told by Philip’s second wife.

“And I was in primary school. And I think maybe that’s also why I haven’t had any curiosity for that side of the story. Because when I was so little, he wasn’t around. And then he was gone.

“I was about 11 years old when I was told and the cause of death was a brain haemorrhage. He was 39 years of age walking along the street and that was it.”

Having discovered all this, Clarke was now fully invested in the search, her overwhelming emotion replacing decades of indifference.

Conveniently, one of the private investigators who had been helping Clarke’s listeners reconnect with lost family was English and knew the genealogy processes in that country.

With only the paternal grandmother’s gifts to go on, she managed to track the family down.

“So what we found out is that dad had a brother, Christopher, who is alive and married,” she says.

“We weren’t sure if there were children, but there was another brother. The idea is to speak to Christopher, and then find out other information about the other brother. Obviously (if they) had children, they’d be close relations of my children and of course me.”

She also found Philip had been buried in an unmarked grave in Brisbane and, in May this year, visited the site with Mary.

As we speak, Clarke is still working through this process and plans to meet with her father’s extended family.

And, despite circumstances conspiring to bury her emotions for decades, she says she was not prepared for the feelings unearthed by the search.

“I don’t talk about my emotions but I am very emotive, and I will cry at the drop of the hat, especially since having kids,” she says.

“But I’ve found it really tricky to share this with people.

“I’m very glad I have, because it’s been such a privilege, people reaching out and telling me their stories.

“But at the same time, normally I will deal with issues and then I think ‘Yep, yep, no worries’ – I shut up that box and everything else that goes with it.

“If it comes up again, in my head, I’ve already closed that up.”

It’s fair to say, this has taken a significant emotional toll and Clarke is still working out exactly what that means.

For now, she just wants to keep digging.

“I think increasingly as an age thing … we really start to respect and hold dear stories that our older generations have had and too often they get lost,” she says.

“Too often people pass from your life and it’s not until their funeral or afterwards, that you might actually have found stuff out about them.

“I’d like to know what Philip was like. I’d like to know if Mum’s representation of him is how he always was and how true it is. I mean, I’m not calling her a liar. But you know, that’s her experience.

“Was that him and was he always like that?

“I’d love to know how he grew up. I’d love to know what my grandmother was like because obviously, she must have been a thoughtful lady if she was taking the time to send gifts to me and getting nothing back.

“And then I would like to know – after me – what his life was like.

“Now, maybe I’m punishing myself, I’m wondering if he cared or even fought to come and see me, or was interested, and I’d like to know why that didn’t happen.

“I might never find that out. And I’m at peace with that as well.

“You know, life is tricky.”

Clarke’s curiosity has also had some interesting side effects.

It’s helped her reflect on her relationship with her husband, Crows AFL coach Matthew, and children Eloise, 13, Sam, 11, and Madeline, 8.

Their lives are a world away from Clarke’s boarding school upbringing in Brisbane and her adolescence of self reliance.

“I remind the kids ‘you know Mummy loves you’. They are like ‘Mum we know, you tell us all the time’,” she says.

“That’s because that’s not my growing up and I’m also very open and we talk a lot more with kids now.

“I don’t know if I’d gotten older with Mum and Dad, I might have had that relationship. But going to boarding school, we didn’t have those big chats because there just wasn’t the opportunity.

“But with my kids, they know everything, we talk about things, and it’s just a different relationship. I think I’m going so far the other way.”

The children are processing the search for grandpa and other family members as, well, like children.

“I mean, they’re funny, but they’re also, what, 13, 11, and 8,’’ Clarke says.

“Eloise is in that lovely teenage stage where she’s just, ‘Oh, they’re probably dead’. The youngest one, Maddy, is holding out hope that we might be related to a princess. And then the middle one, Sam, is kind of like, ‘well, you know, does this mean I could have superhero powers’?”

It’s brought her closer to her radio show producers, and her co-hosts Max Burford, Shane Lowe and comedian Eddie Bannon.

“Max is so close to his family and he talks about how he still goes to his mum’s house, it’s been quite foreign to him to actually sit there and listen to someone do this,” Clarke says.

“And Shane, he’s been really lovely, and they both have been really, really supportive through it all. Shane’s got a really soft heart and a soft underbelly, so he’s been crying along with me.”

It’s also brought her closer to her audience.

“I have had that many texts and Facebook notifications and Instagram comments, and everything else because people are wanting to wish me well and also tell me their story,” she says.

“I’ll need to give myself a break and sort of deal with it all, but I will reach out and I’ll come to their stories. Right now I couldn’t give them the time that they deserve.

“Their support has been absolutely eye-opening and every time I’ve got to that level of discomfort going ‘should we be putting this on radio?’, then someone will say ‘thank you so much for doing this. You know, you’ve made me and my upbringing seem normal’.

“I was at an event and there was a lovely girl who just sat down and she just (opened up and told me what she had been through).

“It’s been incredible. And it shows you the privilege of the job that I get to do.”

Finally, her search has also helped open up new lines of communication with mum, Mary.

“I think that has been the best thing about it, that I’ve actually had conversations with her that I’ve never had, and I feel closer to her,” Clarke says.

“She’s really interested and she sort of expressed regret that maybe she should have done more to keep Philip in my life.

“Other than that, I think she’s really just curious now, really curious.”

Mary confesses the search has raised regrets, which had not surfaced previously as she got on with her life after the break-up.

“If you had asked me several years ago, no,” she says. “But now that (after so long) family conversation is paramount and very much open the way it should be, then yes.

“If I had spoken more about things (at the time) then it could have been a different situation but better late than never, and without regrets. C’est la vie.”

The one thing Mary says now is that Philip loved his baby daughter, telling her she was the “apple of his eye” when born.

The remaining pieces of the puzzle will be left for Ali Clarke to put together herself. ■

For updates on the family search go to mix1023.com.au, or tune to 102.3 on FM radio