Adelaide Festival celebrates our Indigenous trailblazers

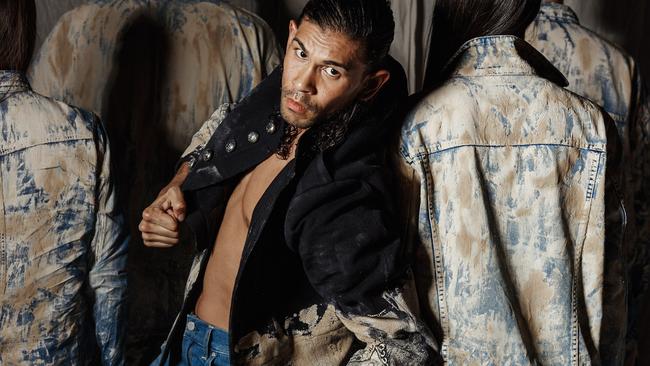

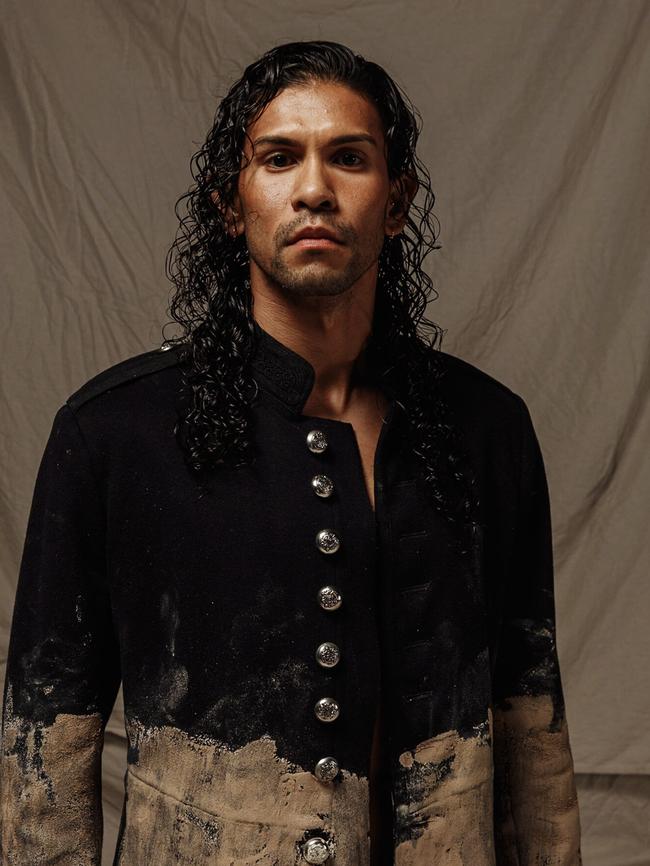

Indigenous shows stretching far beyond traditional imagery and subject matter are at the very centre of this year’s Adelaide Festival program.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

An Indigenous tracker who worked for the NSW police force was a pioneer, treading “both worlds” of black and white, and became the first to rise to the rank of sergeant.

An Aboriginal leader who led a delegation to the German consulate in Melbourne with a petition protesting the “cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi government of Germany” – one of the first rallies against the Nazis’ actions in the world.

A searing commentary on incarceration and xenophobia.

These stories form the heart of this year’s Adelaide Festival, pushing, prodding and re-examining the boundaries between black, white and even international cultures.

“Tracker is a very personal work of mine … about my great-great uncle, who was a black tracker with the New South Wales Police Force,” Australian Dance Theatre artistic director Daniel Riley says of his new work. “So these are the stories of my family and of my ancestral Wiradjuri country, telling me the way it needs to be told.”

Daniel’s great-great uncle Alexander “Alec” Riley was a Wiradjuri elder and black tracker with the NSW police force for 40 years early last century, becoming the first Aboriginal to rise to the rank of sergeant in 1941.

His most notable cases included the capture of Roy Governor (brother of bushrangers Jimmy and Joe Governor), finding a barefoot six-year-old girl who had been lost in the mountains for 24 hours, and tracking serial killer Andrew “Mad Mossy” Moss.

“Alec Riley is important because cultural men like that wilfully chose to stand at the precipice of enforced colonisation, as well as standing truly and wholly in his culture – being that one in the middle, to keep his family safe whilst working for the NSW police force,” Daniel says.

“That’s courage and that’s also strength.”

Black trackers were among the first people to “tread in both worlds,” says Daniel, who never met his great-great uncle. “I’m working with some cultural advisers and cousins and aunties of mine who were Uncle Alec’s granddaughters, so they remember what he was like, because they sat on country with him on the reserve and the mission,” he says.

“They listened to his stories, he cooked for them, so they have a greater sense of who he was.

“We have First Nations peoples in our histories across 250 nations in this country that were enforced to work within these western systems. But then there are also First Nations people in our history, and today, who wilfully choose to do that. I do the same thing. I’m working for an organisation that is not wholly First Nations driven, but I’m doing that wholly with a cultural lens.

“To be able to bring works like Tracker into the ADT repertoire is really exciting and it’s most definitely a first for ADT to be presenting a work like this; that is a full First Nations cast and creative team.” Tracker has been created with Ilbijerri Theatre Company, including co-director Rachael Maza – whose late father Bob Maza founded Australia’s first Aboriginal theatre company – and playwright Ursula Yovich, of Barbara and the Camp Dogs acclaim.

“Tracker is looking at Uncle Alec’s cases and how a modern day, contemporary living Wiradjuri man is inspired by or uses these cases to connect to his identity and connect to home,” Riley says.

“I stand on his shoulders and our family stand on the shoulders of our elders who, at those times, made big decisions and worked within these kinds of systems.”

Lou Bennett, who came to fame with ARIA Award-winning vocal trio Tiddas in the 1990s,is now an academic who completed her doctorate on Aboriginal language retrieval and reclamation in 2015.

Her collaboration with composer Nigel Westlake and songwriter Lior – Ngapa William Cooper – sets the story of the Aboriginal activist, who was also her great-great uncle, on the international political stage.

“Uncle William was the brother of my great-great grandmother, Granny Ada Cooper. The stories of all of my ancestors have been told around kitchen tables, around loungerooms, around campfires, at bedtime,” Bennett recalls. “We have a fairly extensive storyline of Yorta Yorta ancestors … Uncle William being one of the many that have forged forward for justice.”

In 1938, Germany’s Nazi Party forces launched their first major assault against the Jewish population, destroying synagogues, incarcerating 30,000 men and attacking businesses in what became known as Kristallnacht – the Night of Broken Glass.

At the time, William Cooper was secretary of the Australian Aborigines’ League and led a delegation to the German consulate in Melbourne with a petition protesting the “cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi government of Germany” – one of the word’s first rallies against the Nazis’ actions.

“On the 20th anniversary of the end of World War I, William opened up the paper to see if there was any mention of his son, Daniel, who was killed fighting with the Australian Army, and that’s how we came across the article about Kristallnacht,” Lior says.

“He read this article and was obviously shocked at the events unfolding. He waited to see what the reaction was going to be and he was dismayed and disillusioned by the silence that ensued, and felt that he had to stand up and take responsibility.

“In exploring some of the lyrical content of this work, I took this very question to Lou and I asked what are the sorts of things that he would have drawn upon to both attain the courage and the motivation to take action in the face of such silence?”

Bennett believes it was to protect his family, in the broadest sense.

“When I say Yorta Yorta family, I mean the country, the ancestors, the community, the animals – everything about that beautiful country up there,” she says.

“It’s about family and relationships, and we are all connected – every single living being that lives on this earth is connected. That’s the core of who we are and how we look after each other.

“For uncle, it was about the family of humankind, of mankind – that he saw the injustices happening not only to his Yorta Yorta people and to other Aboriginal people, but saw it globally.

“He knew that he had to act upon that – and I don’t believe he could have rested without doing that.”

Lior first became aware of Cooper’s story through the Melbourne Holocaust Museum.

After the continued success of their 2013 symphonic song cycle Compassion, he and Westlake had been searching for a thematic subject on which they could work together again.

“Nigel and I felt strongly that we wanted to embrace a second work, particularly given how much we enjoyed working on Compassion together and the resonance that it has had on audiences since its premiere,” Lior says.

The pair wanted their follow-up to be “both a stand-alone work but also a sort of extension to Compassion” which was “very much grounded on philosophical and theoretical texts and ideas”.

“Upon learning of the story of William Cooper – and in particular, the protest following the events of Kristallnacht – I felt really drawn to telling the story of an icon of Australian history who needs to be remembered more widely, both for who he was and for his actions, and also for this event, which I felt that in particular related to my lineage and my history,” Israel-born Lior says.

It was an extraordinary event in that era for an Aboriginal leader in Australia to take up the cause of the Jewish people “on the other side of the world”.

“In the context of not having his people’s own basic human rights, it’s an incredible act of both courage, and also being a visionary,” Lior says.

Lior and his co-writer Sarah Gory first created a lyrical narrative for Westlake to orchestrate. Westlake also suggested sections for Bennett to translate into Yorta Yorta.

“So it’s my role within these contexts to bring it off the page and to sing it back into life,” Bennett says.

“Part of that is bringing my old peoples’ voice forward. So when I sing in language, I often sing from a different place in my body, and I can feel it.”

At one point, where Bennett was meant to echo Lior’s sung line, it didn’t feel right until she translated it into Yorta Yorta. It now also echoes the shared experience of persecution and massacre of the Jews in Europe and the Aboriginal people in Australia.

“These are big stories that we’re holding on to … I’ve known of the Jewish plight since I was a child, because my family told me those stories, understanding that there have been injustices globally,” Bennett says.

“There has been attempted genocide globally but still, those people are resilient and they rise and they’re still here with us.”

Broome-based Indigenous and intercultural dance theatre company Marrugeku specialises in creating intersectional and trans-disciplinary work. Its video with rapper Beni Bjah, This Is Australia – which has gone viral – is a searing interpretation of Childish Gambino’s US hit, This Is America, and was developed at the same time as its Festival show, Jurrungu Ngan-ga (Straight Talk).

Joint artistic directors, choreographer Dalisa Pigram and director Rachael Swain say it is the biggest project the company has taken on, not only in terms of scale but also its journey to the stage. Originally scheduled to premiere at festivals in Hamburg, Germany and Darwin in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic led to it being rescheduled for a European season in 2021, then further postponed, until finally opening in Sydney and Melbourne last year.

Marrugeku’s work is not only intercultural but also crosses over many mediums and genres.

“The interdisciplinary nature of the practice grew out of our early work in Arnhem Land where … we needed to build this interdisciplinary language to be able to express the kind of reality that we were talking about,” Swain says.

“It emerged from creating work in Indigenous contexts where the understanding of the present holds the past and the future in any one moment.”

Jurrungu Ngan-ga takes this a step further by bringing a contemporary group of outsiders into the mix, in the same way that indigenous cultures have been treated as outsiders in their own country.

“We had a sense that we wanted to talk about fear of cultural difference – and how Australia locks away that which it fears,” Swain says.

The duo happened to meet with WA senator Patrick Dodson, who is also Pigram’s “pop”, on the day that Australia’s Shame, a documentary expose on the Don Dale Detention Centre, aired in 2018.

“He was talking very directly about the juvenile justice system,” Swain says.

“He made the link straight away to our locking up of refugees on prison islands … how we started as a penal colony in terms of non-indigenous people living in this country, and it harks back to a colonial relationship with that which we are afraid of,” Pigram adds.

Dodson likened the situation to Kurdish-Iranian journalist and former Manus Island detainee Behrouz Boochani’s 2018 book No Friend But the Mountains.

“We found a lot of resonance through his collaboration with (Iranian-Australian philosopher) Omid Tofighian, who helped bring a philosophical, broader way of thinking to some of the ideas. One of the things we learned was that specific systems are built into ways of dehumanising or further controlling a group of people,” Swain says.

“Being given numbers, being given oversized clothing, or stripping you of your identity and your culture and any connection with family – those kinds of mind games that go on to bring a person down or break a people down all seemed way too familiar,” Pigram elaborates.

“As we were learning about the refugee experience and those that were locked up on these prison islands, their experiences seemed very similar to that of our families and generations before.”

Another short story by the late American author Ursula K. Le Guin, The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, also provided inspiration.

“It speaks about this thriving community that has lots to celebrate but they get to live this life knowing that a child is being neglected and hidden in a dungeon.

“You have to face that and work out whether you stay or you walk away from that life that you’ve been enjoying at the expense of that young person’s neglect,” Pigram says.

“That also spoke a lot to this country and how the people who are the first people of this country continually live lives that are facing it hard because of the ongoing effects of colonisation, that continue to impact on our next generation. So you know those that call this place the Lucky Country don’t have the same lived experiences as the First Nations people, that’s for sure.”

As well as performers from many of Australia’s different First Nations, the work features dancers from Palestine, the Philippines and Irish-English backgrounds, and draws on their dance styles ranging from traditional to contemporary street styles like Krump and

hip-hop.

“We’re so privileged to work with some amazing artists that come with their dance and cultural languages, that live within their bodies,” Pigram says.

“Our process is one that draws from all of those languages.”

Swain says the whole work takes place “within the psyche of Australia as a kind of prison of the mind” and responds to “potent images from the media from the last 10 years”.

The concept of Straight Talk is embodied as performers directly address a security camera, which represents the viewpoint of the audience, but it also has another meaning.

“In relationships in our kinship terms, for example, your mother-in-law and son-in-law can’t speak directly, so they have to talk around (through intermediaries),” Pigram says.

“My pop Patrick Dodson was saying how black and white Australia have never done that direct talk … we’re always going around things on different wavelengths, never kind of quite coming straight at it.”

Swain says Boochani created a new literary genre which he called “culturally situated horrific surrealism” which she and Pigram also felt applied to the documentary Australia’s Shame.

“In Australia, we treat our borders very harshly. There are many ways that this project looks at breaking down borders – Marrugeku’s practice has always been about building bridges.” ■