Adelaide Festival 2023: Your ultimate guide and six of the best shows

The Adelaide Festival can be overwhelming with just how many shows are on offer – so here’s our guide to six of the best.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Duality plays a big part in the 2023 Adelaide Festival.

For starters, it is both the sixth and final program curated in large part by former artistic directors Neil Armfield and Rachel Healy, and the first to be delivered by their successor, Ruth Mackenzie, who has stepped in early to allow them to move on to other projects.

Next year marks a return to what Mackenzie calls a “full strength” international program of theatre, music and dance after two events where travel was severely limited by the Covid pandemic.

“We’ve got international storytellers coming back in some cases, and coming for the first time, from around the world,” says Mackenzie, who will go on to present her own programs for the 2024, 2025 and 2026 Festivals.

Alongside next year’s previously announced opera centrepiece, Giuseppe Verdi’s Messa da Requiem, by Ballett Zurich, the line-up revealed this week features new works from “two of the great discoveries under Rachel and Neil’s time”.

Belgian-born director Ivo van Hove, who presented the epic Shakespearean trilogies Roman Tragedies in 2014 and Gods of War in 2018, will return with his Internationaal Theater Amsterdam’s four-hour adaptation of Hanya Yanagihara’s best-selling contemporary novel A Little Life.

The creators of the 2017 Festival’s incredible dance theatre work Betroffenheit, Canadian actor-playwright Jonathon Young and choreographer Crystal Pite, are also back with their work Revisor, which deconstructs Nikolai Gogol’s classic Russian satire, The Government Inspector.

In all, next year’s Festival will contain 52 events, including 11 world premieres and eight Australian premieres, with 17 shows exclusive to Adelaide, and artists and writers from 18 countries stretching from Belarus to Belgium, Finland to France, Palestine to Portugal, Ireland to India, and Switzerland to South Africa.

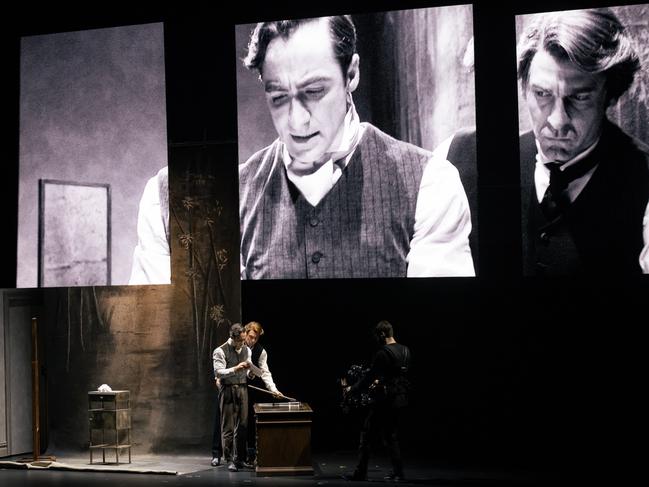

STRANGE CASE OF DR JEKYLL AND MR HYDE

In a rare case of the Festival presenting a direct sequel work in successive years, the 2023 program includes the return of Sydney Theatre Company under director Kip Williams, following the sellout acclaim of this year’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, with the second of his “cine-theatre” spectaculars, the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde – perhaps the most infamous but oft misinterpreted story of a split personality in history.

Like Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella about a respectable doctor who transforms into a murderous brute had fascinated Williams since his youth and was something he revisited throughout his studies.

“I see Jekyll/Hyde as the second part of a trilogy of works that I am making in this particular form,” Williams says.

“While each work is distinct in its own right, and those who saw Dorian will be in for some great surprises and thrills with the approach towards this particular work, the interrogation of Victorian gothic through the cine-theatre form is something that I am exploring across three productions.”

Williams has not yet announced what the third piece will be, but it will premiere at the start of the company’s 2024 season.

While Dorian Gray began in an empty theatre and took its initial visual cues from Victorian-era England, that work “pivots into a much more contemporary mash-up of different eras in the intervening century” and its style crossed genres, music and wardrobes as its central, ageless character evolved.

“Jekyll/Hyde is a work about unmasking that public identity and burrowing into the truth and complexity of somebody beneath the public mask,” Williams says.

“We start in a fully immersed, Victorian gothic universe and, over the course of the production, that gets peeled back … as you start to get to the central question of who is Jekyll and who is Hyde?”

It might be natural for audiences to assume that the two actors would each be playing one of the title characters, but that is not the case.

In fact, Ewen Leslie, of TV series The Cry fame, plays both the doctor and his savage alter-ego, as well as all of the other characters in the story, while Matthew Backer plays just the one role, the oft-forgot protagonist of Stevenson’s original novella, Jekyll’s best friend Gabriel John Utterson.

Williams says this production is just as concerned with the question of who Utterson is.

Oddly, it was Backer’s experience as a children’s TV presenter on Play School which helped him adjust to the live camera on stage.

“When you start on Play School, the first thing they say is to talk to the camera like it’s one kid – so you are not trying to present to a whole room,” he says.

“Also, Play School is so much about patting your stomach and rubbing your head … doing multiple things at once while trying to look cool, calm and collected, talking to a camera.

“That is what this show is: Ewen and I are having to hit 500 marks every night with millimetre precision while also trying to look quite naturally at ease in a

hi-tech show.”

In Stevenson’s book, Utterson is a London lawyer who investigates a series of strangeevents which seem to link his old friend Dr Henry Jekyll and a brutal criminal named Edward Hyde.

“The myth of Jekyll and Hyde has morphed over the years, and everyone knows the big twist. What we have to do now is take that twist and present it to them in its original form … but make them second-guess themselves with how much they know,” Backer says.

“Stevenson has really quite beautifully written a protagonist who isn’t your usual hero … it’s this uptight, fastidious, introverted, quite cold, acerbic lawyer. The audience follows the mystery through his eyes. I think it’s such a wonderful flip on an audience’s expectations.”

Rather than a monster story, Williams says his version of Jekyll/Hyde is about a much more internal struggle that becomes externalised.

“I think Robert Louis Stevenson is much more concerned with the monster of society, and the notion of societal regulation as a monstrous force that results in people compartmentalising themselves and subsequently suffering the cost of concealing an authentic part of their being.

“He’s writing in a way that feels incredibly coded in the Victorian period, because there are lots of things he is only able to infer, that we are able now in 2022 and 2023 to explore far more openly and explicitly.”

From a technical perspective, Jekyll/Hyde again employs many of Dorian’s devices to create what Williams labels his “cine-theatre” works – multiple video screens which move above the stage while camera crews capture performances live on stage.

This time, black-and-white images deliberately evoke the classic horror and noir detective movies of the 1930s and ’40s, as well as the mystery of early Hitchcock films.

“There are certain rules that come with those genres, that we initially adhere to and then start to break in the piece, as we get closer to the truth,” Williams says.

“The way that screens work in this production is really fascinating … so much of the story is about the compartmentalising and fracturing of self … the way in which humans have this extraordinary capacity to distil themselves into different personae based on the different contexts which they inhabit.”

AIR PLAY

A circus in war-torn Afghanistan probably sounds like the most unlikely place for two clowns to meet and form a double act – let alone the starting point for a love story.

Yet that’s exactly what happened for Texan-born former ballerina and Princeton graduate Christina Gelsone, and globetrotting juggler turned Ringling Brothers clown and teacher Seth Bloom – aka the Acrobuffos.

Having previously performed at the Adelaide Fringe in its street buskers program, next year the New York-based duo will realise a dream by graduating to the main Festival stage with its physical theatre show Air Play, a collaboration with kinetic sculptor Daniel Wurtzel.

Washington DC-raised Bloom’s father worked for the US government providing relief aid, and so the family moved around every three years while he was growing up, including stints in Kenya, India and Sri Lanka. In 2003, he was invited to take part in a circus project for children in Afghanistan, where his mother also happened to be working for the United Nations.

“It went around and did performances on social issues – for health care, for malaria prevention, for landmine awareness – mostly training local Afghans to use theatre for social change,” Bloom says.

Gelsone, meanwhile, had relocated to New York City where she joined a company called Bond Street Theater, which works with refugees in post-war zones around the world. “I was in Afghanistan in 2003 with them,” she says. “I think both the organisation Seth worked for and the organisation I worked for still currently have projects in Afghanistan – even with the tumultuous year that’s been happening.

“It’s a fascinating place to have met each other. Seth saw me performing in front of a bombed-out high school in Kabul.”

Over time, Bloom and Gelsone ended up swapping between companies in Afghanistan, and their paths continued to cross.

“Seth and I ended up working together quite a bit. It was clear that when we were on stage, I was funnier with Seth, and Seth was funnier with me. When you find a clown partner like that, you hold on for dear life. It was not intentional to start dating or kissing him,” Gelsone laughs. “That came about a year or two later,” Bloom interjects.

Despite the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan, the duo says they performed there in relative safety.

“I know the news coming out of Afghanistan is horrific … but what we got to see, because we didn’t have guns and we weren’t military, was the genuine families of Afghanistan. I have learned how to be a better person, and how to be a better host, because of my Afghan friends,” Gelsone says.

“Everybody wants to have their family, for their kids to grow up and go to school and be safe, to take care of their older parents. There’s a lot of connective tissue being a human.”

The couple became engaged while street performing in Scotland, got married in China, and are speaking during a rare stop at their apartment home in New York City’s Harlem neighbourhood.

Acrobuffos make shows without words, so they can travel internationally.

“We really got our chops on the street – there’s no better teacher than an audience that can walk away,” Gelsone says.

Having met “consistently fantastic” Australian street performers in Edinburgh, the pair came to the Adelaide Fringe in 2015 as part of the buskers’ festival organised by their Adelaide friends Mr Spin, aka Nigel Martin, and his UK-born wife Louise Clarke. They performed a street show called Waterbombs, which has taken the Acrobuffos to 28 countries around the world.

This time, the Acrobuffos will get to perform Air Play on stage in a proper theatre.

“Christina in late 2010 saw a video on Facebook of one of Daniel Wurtzel’s air sculptures called Pas de Deux, where there is a circle of fans and two pieces of fabric swirling around each other,” Bloom says.

Wurtzel lived in nearby Brooklyn and the trio built Air Play in bits and pieces over the course of five years, constantly bringing new ideas into the mix.

“There’s one scene with kites, where these huge 20-foot fabrics are flying over the heads of the audience – that started off as just a plastic bag flying on a string,” Gelsone says.

Air Play examines how air-filled, air-related or air-elevated devices can be used to create a combination of sculptural forms and dance-like movement. “We started playing with the philosophy of air,” Gelsone says. “I really wanted to change the air inside the audience’s lungs – so we specifically change the rhythms so people start to breathe faster or slower, depending on what the scenes are. Because it’s a non-verbal show, people are bringing their own feelings to it – their own breath, their own story, their own inner life makes the show come alive as well.”

Air Play is at the Festival Theatre, March 15 to 19. Book at adelaidefestival.com.au

REVISOR

One of the most startlingly original and deeply moving performances in recent Adelaide Festival memory was the 2017 presentation of Betroffenheit, a collaboration between Canadian writer-actor Jonathon Young and choreographer Crystal Pite.

Through constantly evolving repetition and routine, it gradually pieced together events surrounding the tragic, real-life fire which killed Young’s 14-year-old daughter, along with his niece and nephew, and the aftermath that kept him trapped in a never-ending loop.

That work has developed into an ongoing creative relationship between Pite and Young, sometimes under the umbrella of her dance company Kidd Pivot – as is the case with next year’s Festival attraction Revisor – and sometimes in conjunction with his theatre group the Electric Company.

Recorded dialogue and movement which explores the relationship between language and body suggest some stylistic similarities between Betroffenheit and Revisor, which reworks Russian dramatist and novelist Nikolai Gogol’s satirical 1836 classic The Government Inspector.

“We had talked about the genre of farce, and how that extreme physical comedic form was something we were interested in – especially when we were dealing with a dark subject matter, like we were in Betroffenheit,” Young says.

“I wouldn’t say we ever quite came close to something farcical, but nonetheless that genre was hanging around as we talked about our next piece.”

Pite asked whether there was a farce that Young would like to adapt or record. That was when he brought The Government Inspector into the mix.

“What if we take this full-body ‘limb-synching’ as someone has called it – as opposed to lip-synching – and do an entire play? See if we can do, similarly to what we did with Betroffenheit, which was deconstruct it, or take it apart, or find what’s underneath it.”

Gogol’s original play was itself a dangerous act at the time, satirising greed and stupidity and the political corruption of Imperial Russia. Ironically, it was approved by Tsar Nicholas I, who reportedly found the work hilarious and hugely entertaining.

Young says its themes are equally relevant today, as the world reverberates to the actions of present-day Russia, its invasion of Ukraine, and the behaviour of its president Vladimir Putin.

“It’s all accidental, of course, because we started writing this before there was any crisis, but I don’t see how anyone could watch the show and not have that come to mind. Let’s not forget that Nikolai Gogol was a Ukrainian, who made a name for himself in Russia as a Russian writer. Part of making a name for himself was to use the Ukrainian folk stories that he grew up with, and bring them to St Petersburg because they were in vogue. So there is something interesting and complex there as well.” ■

Revisor, Her Majesty’s Theatre, March 17 to 19. Book at adelaidefestival.com.au

THE SHEEP SONG

Yet unconventional Belgian theatre company FC Bergman has chosen the conventional form of a morality tale to tell its story about a sheep who breaks from the flock mentality and strikes a Faustian deal to experience the human condition.

“We tell a fable or morality play about a creature that wants to become more than it is destined to be,” says one of the company’s six co-founders, Stef Aerts.

“He all of a sudden gets on two legs, to transform in a more-or-less human way, but he doesn’t become totally human. The physical act of standing on two legs is not the biggest challenge for this sheep.

“The real issue is that he becomes like a victim of the human way of thinking, of ambition and morality … of good and evil, right and wrong.”

This will be the Antwerp company’s first trip to Australia, and only its second outside Europe, having just made its debut in New York with a different work, titled 300 el x 50 el x 30 el – based on the Biblical dimensions of Noah’s ark.

“When we started our company almost 15 years ago, we didn’t really have a plan – it was more or less by coincidence,” Aerts says. “We were at theatre school together, and in our second year we were asked to create something for a little theatre festival by a squatters’ movement.”

Those actors, artists and theatre makers who put their hands up for the one-off warehouse project eventually formed FC Bergman, creating site-specific works. It was only after 10 years together that the company began creating works for the theatre stage.

“We were educated with Shakespeare and Moliere and so on, trained as classical text actors. The philosophy was that everything was in the text.”

Like all good uni students, they did the antithesis of what their teachers required. “As a group, we were really fed up with it … and we really urged for a more visual, informal way of doing stuff,” Aerts says.

“The Sheep Song is also a wordless piece. For us, it felt a little bit like going back to the roots, because in previous years our productions grew bigger and bigger, and text came back in.

“The Sheep Song felt like really going back to the way we started, doing things just with images and without words, on a very physical level … just a little bit older and wiser, maybe.”

In its early works, FC Bergman often started with an elaborate set design, but The Sheep Song takes place on a mostly barren stage. “We tried to give ourselves some limitations, so we really play in a very dark space – it’s about bringing in objects and actors and lights.”

The stage floor is “like the moving footpath” in an airport terminal. “So you have this pushing energy of the floor that keeps moving, while the rest of the space becomes more and more narrow.”

The Sheep Song was also influenced by 15th and 16th century Flemish Primitives paintings which often have religious iconography or subject matter.

“The gothic and High Medieval art depictions of sacred lives and saints are very two-dimensional, so it’s a very flat way of depicting figures. That’s something that we really try to achieve as well in this performance,” Aerts says.

“In the High Middle Ages, this gothic period, you also find that the theatre begins to flourish … as does science.

“Then the Renaissance came … the Flemish Primitives introduced perspective in visual arts, but also the understanding of the Bible became less dogmatic and there was much more room for interpretation.

“That’s really where our performance, our story, ends. We make this timeline of going from the High Middle Ages into the Renaissance, and that’s where our main character is left, with all these questions.

“He is lost in thoughts, but also literally in space. This quest goes parallel to the quest that arts and sciences made in Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries.”

In the end, The Sheep Song is a morality tale without a moral.

“We chose the formal aspect of a morality play just to show that this way of telling stories is not sufficient anymore … it’s very black and white, about good or evil,” Aerts says. “Nowadays, if we talk about what it is to be a good human, it is much more ambiguous.”

The Sheep Song, Dunstan Playhouse, March 16 to 19. Book at adelaidefestival.com.au

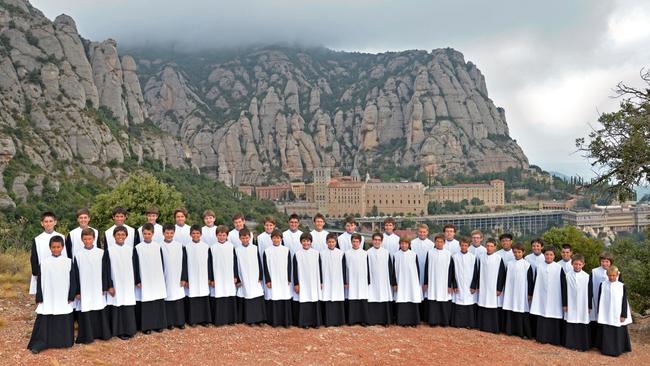

ESCOLANIA DE MONTSERRAT

Nestled high between the jagged peaks of the Montserrat mountain range, 50km northwest of Barcelona, lies an ancient Benedictine monastery which is also home to one of the great vocal wonders of the world.

Escolania de Montserrat is an extraordinary ensemble which has also topped the BBC Music Magazine’s list of the top 10 choirs in the world but – unlike its better known counterparts the King’s College Cambridge and Vienna Boys choirs – has never performed in Australia.

Until now, that is, with the Escolania’s exclusive Australian premiere scheduled for next year, when 36 boys aged between nine and 14 years will bring their soprano and alto voices to the Adelaide Festival.

The Escolania choir’s origins are among the oldest in Europe, with documentation and reference to its robes dating back to the start of the 14th century, although the mountain has been a site of religious significance since pre-Christian times, when the Romans built a temple there to the goddess Venus.

Legend has it that the Virgin of Montserrat, one of Europe’s famous “Black Madonna” statues, was hidden there in 718 to avoid the invading Saracens, and that the Benedictines later built their abbey around the sanctuary.

“It was common in the past that Benedictine monasteries had schools. In our case, the community was founded in 1025, and in 1307 we have the first documentation showing the existence of Escolania,” says its current headmaster, Father Efrem de Montellà.

“The main job of the monks is to take care of the sanctuary, and for that reason we have a boys’ choir: we want that the pilgrims can experience God through the beauty of the music.”

Today, the Escolania comprises more than 50 boys from towns in Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Valencian community, who complete courses at primary and early secondary levels. Each student must study two instruments, including piano, as well as learning about musical language, the orchestra, and participating in the choir.

Choir director Llorenç Castelló says the first part of the Adelaide concert program will consist of works by Montserrat composers or those who have written music especially for the Escolania.

“Therefore the first part will be a small sample of religious music from the XIV century to current music. It is music that you can hear in the Basilica during the liturgical year, all of them dedicated to the Virgin Mary who is the patron of our Basilica,” he says.

“It is another objective of Escolania to export Catalan language and culture around the world. For this reason the second part will present popular music by Catalan composers, too. They will be folk songs with original arrangements from Catalan composers and pieces of their own creation.

“Among them we will be able to hear El cant dels ocells, for example, which both popularised the celebrated cellist, composer and conductor Pau Casals but in this case with a new reading by Bernat Vivancos, one of our most internationally renowned Catalan composers.”

In 2010, the church installed a new pipe organ, replacing the original one from 1896, and this often accompanies the choir.

“Currently, every summer we offer an International Festival of Organ in which international organists are renowned participants,” Castelló says.

“Although Escolania sings a cappella on many occasions … most of the repertoire for Escolania – from the Baroque period to current days – is written with organ accompaniment.

“The first part of our program will need the accompaniment of pipe organ while the second part will need the piano accompaniment.”

Escolania de Montserrat, Adelaide Town Hall, March 3 to 5. Book at adelaidefestival.com.au

A LITTLE LIFE

When two trusted associates each gave acclaimed theatre maker Ivo van Hove a copy of the same book within a matter of weeks, he knew they must be on to something good.

Upon return from his summer holidays in 2015, van Hove met with his company’s dramaturge for one of their regular catch ups. “He gave me this little plastic bag with a very thick book in it. He said, ‘I read this over the summer – it’s really something for you.’ I thought I would read it once, but not immediately,” van Hove recalls.

“But then I met an actress, who is one of my best friends, three weeks later for a lunch, also to catch up after the summer – and she had a little plastic bag with a book in it. She said almost the same words: ‘This is something for you.’”

Then van Hove felt compelled to start reading the book: A Little Life, by American writer Hanya Yanagihara.

“What happened to me is what happened to a lot of people all over the world: I couldn’t stop. I immediately thought, I am going to apply to bring this to the theatre.” Belgian-born van Hove’s work with his company Internationaal Theater Amsterdam (formerly Toneelgroep Amsterdam) is already familiar to Adelaide Festival audiences from his two epic Shakespeare trilogies, Roman Tragedies in 2014 and Kings of War in 2018.

At around 800 pages, the source material for A Little Life makes for a play of similar proportions – with a running time of four hours, including interval – but with more intimate subject matter. “The first 80 pages, more or less, it is what it is: Four men, coming to New York because they want to make it there. Been it, seen it,” says van Hove. “But then the book focuses page by page on one person, Jude St Francis. It’s clear that something is really wrong with him, but at the beginning you are not aware what exactly is wrong.

“It’s not a gay novel at all – it is about structural sexual violence and sexual abuse of a young boy, from a seven year old to when he is 15, and the catastrophic consequences it has for the rest of his life.

“I’ve never read a book which dived so deep into this theme, and into this hell.”

Van Hove, who had recently worked with David Bowie on the musical play Lazarus, also collaborated with Yanagihara on the script for A Little Life.

One of the things Yanagihara had wanted to explore with her book was the idea of a protagonist who never gets better. The character of Jude becomes caught in a cyclic pattern of abuse and suffering – some of it self-inflicted.

“There is a second really important thing … that he is surrounded by people, by friends and by a kind of mentor who later becomes his (adoptive) father, who really love him and that are really the best friends in the world. Even that doesn’t help,” van Hove says. “It’s a book about sexual abuse but also about real love … really caring for somebody against all odds.”

Much of the appeal for van Hove was that all of the main characters are far from stereotypes. And while Jude is gay, some of his male friends are straight and married; others experiment with their sexuality and are forced to make choices.

In the end it is pure circumstance that pushes Jude to the brink.

To heighten the sense of intimacy, the audience is seated on both sides of a central stage, facing each other through the performance. “By positioning people on two sides of what happens on stage, there is an infinity that we create – which is also for the actors,” van Hove says. “There is a lot going on, which is kind of intense, and it creates for the audience a sort of togetherness. I wanted to create a kind of crucible.”

A Little Life, Adelaide Entertainment Centre Theatre, March 3 to 8. Book at adelaidefestival.com.au