Australian of the Year James Muecke on the terrible price of Australia’s addiction to ‘toxic’ sugar

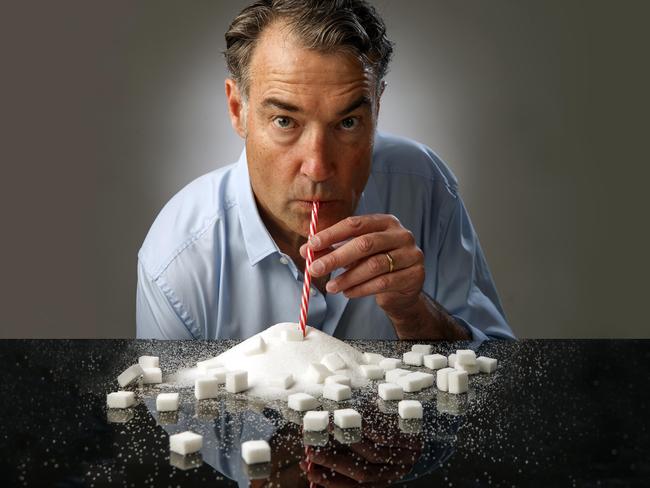

Australian of the Year doctor James Muecke is fighting to stop the spread of a toxin he says is killing and maiming us – sugar.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

James Muecke has leapt into the lion’s den. In a country in love with sugar, the 2020 Australian of the Year has declared it public enemy number one and has already earned hate mail and the ire of industries built on our sweet tooth.

Luckily, the Adelaide eye specialist has faced lions before.

In 1989, as a young doctor, Muecke took a job in a remote Kenyan hospital which served as a base to explore Africa. He wanted to help people, but he especially wanted adventure.

There was the time, for example, when on the way to see the gorillas in Rwanda he and a friend decided to take a detour to visit pygmies in Uganda. Before they could make it, they were captured in a tiny village by rebels trying to reinstate Idi Amin.

“The moment we set foot in the village we were surrounded by half a dozen men who were filthy, drunk and very menacing,” Muecke recalls in his ophthalmology consulting rooms, fresh from a trip to Myanmar. “They immediately tore apart our back packs looking for weapons, and they found a pair of binoculars – we’d been searching for wildlife.”

Accused of spying, the pair was marched at gunpoint to a ramshackle hut at the edge of the village to await their fate. “I was terrified,” admits the 56-year-old, who tells his stories of derring-do with a boyish enthusiasm somewhat incongruous with the rich, reassuring tones of a medical specialist.

“We were convinced if we stayed in the hut they were going to come back and knock us off. So we broke out through the back into the jungle behind. We soon found ourselves in a national park at dusk, with lions and hyena feeding … it’s not where you want to be.”

Fortunately, the pair found a nearby road and hitched a lift to safety from some dodgy locals – but not before more heart-in-mouth moments when they were convinced they were about to be shot and tossed over a cliff on a lonely African road.

You might think that this near-miss would teach the young doctor a lesson – and you would be right. He went on to organise other hair-raising adventures, including joining an armed convoy through the middle of a civil war in Mozambique, being chased down Mount Kenya by a monstrous wild buffalo in the middle of the night, and surviving numerous violent robberies at his Kenyan hospital quarters. Once, his cleaning lady was hit on the head with a boulder; another time a colleague was strung up by the neck from a rafter but survived. Along the way, Muecke contracted malaria twice and dysentery once.

If that seems a bit Indiana Jones, then it’s true that Muecke is a surprise packet: tall and imposing yet with an utterly disarming manner and eclectic array of interests. He was very close to becoming a furniture designer and maker, is a keen photographer, author of a successful guidebook for parents, and even recorded an album with a musician brother.

He has also proved adept at overcoming obstacles: sleep each night is “a lucky dip”, so he often uses his early mornings for walking, thinking and writing; and after progressively losing control over the muscles in his right hand due to a neurological condition inherited from his father – ending his surgical career – he has prepared for life after clinical medicine next year, setting up consulting company Medthink.

And he points back to those wild experiences in Africa for helping him manage challenges and reach where he is now. “These sorts of things make you more resilient,” he points out.

That is just as well, because resilience is something he will need this year, which he has dedicated to tackling one of the biggest health challenges the nation faces.

In these coronavirus days, it’s a difficult message to get across: that there’s another pandemic in the world, maiming and killing thousands of Australians each year, with about 250 people a day acquiring Type 2 diabetes.

But Muecke is determined to have an impact on this condition linked to obesity that leaves a trail of ruined, shortened lives and overwhelms the nation’s health system in ways few realise.

He says he knows his campaign will be opposed by vested interests and critics, but insists that won't deter him from trying to slow the rise of Type 2, which is set to affect 3 million in the next five to 10 years.

Muecke blames sugar, an “addictive toxin” which we need to urgently restrict – a view not totally supported by some experts, who blame wider dietary, genetic and lifestyle factors, like being overweight and not exercising.

While Diabetes Australia chief executive officer Professor Greg Johnson supports Muecke’s campaign, he says the cause of Type 2 is not fully understood. People from China, India, South-East Asia, the Pacific Islands – and Aboriginal people – have a higher genetic risk. Beyond that, fat around the middle, from diet and lack of exercise, also sets the stage for the condition. But excess sugar, by contributing to an unhealthy diet, definitely plays a role, says Johnson.

Muecke is adamant. “It’s all about sugar,” he says. And there is no doubt that once someone is diagnosed with Type 2, sugar becomes a crucial driver of damage from the disease, in which glucose accumulates in the blood as the insulin we produce to drive it into our cells meets growing resistance.

And the damage is extensive: walk through the Royal Adelaide Hospital and perhaps a quarter of the patients are likely there because of Type 2, their large and small blood vessels choked by sugar.

There is the cardiac ward, with heart attacks from blocked arteries and the renal ward with dialysis from kidney failure. There are patients with high blood pressure, and those whose small vessels have become congested, damaging nerves and increasing the likelihood of infections, amputations, impotence, dementia and blindness.

Nor is it a case of one or the other. Some people work through the list of calamities. Muecke says it’s our sixth biggest killer, and a major contributor to the others such as heart attacks, stroke, cancers, and dementia.

These conditions would likely also make COVID-19 much more dangerous.

Not surprisingly, it was Type 2’s potentially catastrophic impact on the eyes that drew the ophthalmologist into the issue. “Type 2 diabetes is now the leading cause of blindness among working age adults in this country,” he says. “An estimated 1.7 million people have diabetes, 1.2m who are known and another 500,000 plus who have undiagnosed disease. But well over half are not having their regular eye checks.”

That’s a big problem because one third of people with Type 2 have eye disease due to their diabetes, and about 100,000 of them are at serious risk of going blind. Yet many don’t even turn up for appointments.

It makes Muecke angry, because the vast majority of diseases and conditions that lead to blindness are preventable or treatable. That is why he became an ophthalmologist, and why he’s devoted more than 20 years travelling to Myanmar – and later, other Asian and African countries – to fight blindness and train doctors through the charity he co-founded called Sight For All.

Hundreds of thousands of people across Asia benefit each year from the eye care that Muecke has helped foster, enlisting the expertise of other Australian eye specialists and providing the training and equipment for local doctors and staff to help their people. The main problem among adults in low income countries is cataract, in which the eye’s lens becomes dense and cloudy – and yet which is readily fixed with surgery.

But Australia also has a developing vision crisis, thanks to Type 2, and just how serious it is was brought home to Muecke two years ago when he was making a documentary on what it’s like to be blind.

That’s when he met Neil Hansell, a man who ticks just about every box on the list of horrible ways Type 2 diabetes hurts you once it gets its hooks in. “Seven years ago, at the age of 50, he went to bed one night with normal sight and woke up the next morning completely blind,” Muecke says.

Losing his sight was only one part of Hansell’s story – as the man himself relates as Muecke and I sit with him in the RAH where he has just had his lower left leg removed, because of Type 2.

Hansell is chirpy, despite his operation. He can still feel his missing leg, and the disconcerting phantom limb pain. Like Muecke, who he says has inspired him, he is keen to sound the alert about sugar.

Hansell was diagnosed with Type 2 at the age of 27. He’d tended to eat a lot of takeaway at work, and not much in the way of vegetables at home. He also drank a lot of soft drink. “Coca-Cola was my downfall,” he says. “I’d drink up to four litres a day. Two two-litre bottles were nothing.”

Did he feel like he was addicted, asks Muecke. “Yes, I couldn’t stop,” Hansell says, although he adds that “you’ve got to take the blame on yourself – at the end of the day it was my choice to eat the sugar”. Nor did he do all that the doctors told him, he says, “and I’m paying the penalty”.

The first serious sign of trouble came after a cramp in his right leg. A blood vessel was blocked. It led to a massive abscess on his thigh which has left a long scar.

Then he saw an optometrist after experiencing headaches, and a specialist detected abnormal blood vessels growing in the backs of his eyes – something that can happen when the healthy vessels become clogged.

He had treatments but then one night those blood vessels bled, and he woke up blind. “I thought I was still sleeping,” he says.

Then, in 2016, after numerous operations had restored 30 per cent vision to one eye, he went down with what he thought was the flu, but in fact was a severe heart attack. His nerves numbed by Type 2, he hadn’t felt it. “Ulcers on the legs were the next issue,” Hansell says, pointing to the scarring on his legs and arms. As the arteries clog, the blood flow is reduced, making infection more likely; as well, the nerves are damaged, so numbness becomes a danger.

That is what happened with his leg. He bought a pair of new work boots and developed a blister without really knowing it, which went on to infect his foot down to the bone. Eight operations, taking a toe here and a chunk of bone there, eventually led to the decision to amputate the lower leg.

Hansell doesn’t want anyone to go through what he’s suffered. “They should be doing ads that smack you in the face like cigarettes,” he says of health authorities. “Don’t sugar coat it: show someone with their leg cut off, or someone getting needles in the back of their eyes. And make it in plain English. Fear is the biggest thing.”

Hansell’s story weighed heavily when Muecke thought about what he’d say if he did happen to be honoured as Australian of the Year on Australia Day. “I wasn’t expecting to win, although I had to have a speech ready,” he says. “It was about loss of vision due to diabetes. And I was thinking: Shouldn’t I be using this platform to raise awareness of the root cause? Which is dietary and preventable? Do I not have a responsibility to do that?”

There was no debate: Muecke had felt a responsibility for other people’s welfare since an Adelaide childhood when he decided he must become a doctor. “There was no experience that made me decide I wanted to do medicine,” he recalls. “Just a desire to help people, to treat people, seemed to be inherent in me.”

His father was a senior CSIRO scientist, which saw the Mueckes – from German stock who settled in the Barossa Valley in the mid-1800s – move from Adelaide to Canberra and later Washington DC. After their return, Muecke studied hard at Canberra Grammar, but missed by one mark to study medicine with his friends at Sydney University. Instead he moved back to South Australia, and the University of Adelaide.

Two things had always fascinated the young Muecke: using his hands, and Africa. He loved to make things as a child and was especially good at building and painting model aeroplanes. Africa was a fascination – he’d watch TV shows such as Daktari and Kimba the White Lion, and dream of adventures on the “Dark Continent”.

At university, those fine motor skills came in handy. One time, he recalls, he was the only person in his class to be able to cleanly dissect free the spinal cord of a cockroach. “I was born for microsurgery,” he says. Yet after all his striving to be a doctor, he started to become disillusioned and wonder if another direction might be better.

Muecke made furniture in his spare time and thought that could be a career option. His work in hospital as a young registrar was not encouraging: many of the people were ill from diseases which he could not cure, like smoking-related ailments. “You were just alleviating symptoms and prolonging lives, you weren’t able to cure,” he says.

He wanted to help, to fix problems. Eye surgery was the obvious answer. “Ophthalmology was the one that ticked the boxes, especially with the microsurgery and the fact that you could cure people. The majority of the world’s blindness is due to cataract and it is highly treatable – you can really do a lot of good in a short time.”

But Muecke also had Africa in his mind, and adventure. That would take him to work as a general doctor in Kenya, survive risky adventures there, and eventually practise ophthalmology and surgery in another trouble spot, the Middle East. By then, he was married to Mena, an Adelaide interior architect.

Muecke rates the year in Jerusalem, 1996, as one of the best of his life with Mena – although both had hairy moments. Mena’s bus to work was blown up just after she’d stepped off; he was lucky to escape being torn apart by an angry mob while travelling in an ambulance in the West Bank, when Palestinians mourning the death of a local fighter mistook him for an Israeli.

By 1998 he was back in Adelaide, in medical practice, but still needing travel and adventure. Henry Newland, head of the Royal Adelaide Hospital’s eye department, who was working to help cure and prevent blindness in Myanmar, gave him both, plus the chance to use his surgical skills.

Myanmar’s need was enormous, but the challenge was also great. Muecke was up for it. His poor sleep allowed him to rise early in Myanmar and take beautiful photographs that he put into a book that raised more than $100,000. “We used that money to train and equip the first children’s eye specialist for the country,” he says. That doctor provides 30,000 treatments every year and, more importantly, is training his own colleagues.

Now the Australian of the Year has a tougher task: training his fellow Aussies to realise the danger they are in.

He’s convinced sugar is the root cause. He’s not just talking cakes and soft drink, but potatoes and white flour, white rice. The source of the problem, he contends, was a change in the American Dietary Guidelines four decades ago which recommended decreasing fat by 30 per cent and increasing carbs by 60 per cent. Reduced fat meant sugar was added for flavour.

That rise in carbohydrates has been a disaster for our health, he says, with a fourfold growth in Type 2 diabetes globally, six-fold in South-East Asia, and 80-fold for Aboriginal communities. Muecke also points to studies that show the US sugar industry in the 1960s shifted blame for heart disease to fats and cholesterol away from sugar, despite evidence it played a role.

Muecke was no angel on sugar though. “Until very recently there was virtually no meal which I didn’t complete without a large bowl of ice cream,” he admits. “We have cream biscuits in the tearoom here (at his surgery) and I used to demolish a pack over a day.”

So ahead of this campaign, he “detoxed” from sugar. “It’s as addictive as nicotine,” he insists, admitting his withdrawal symptoms were unpleasant over a few days of irritability, headaches, clouded thoughts. The kilos “have dropped off”, he says, and now he can walk by a piece of cake without reaching for a slice or two.

Can he convince the rest of us to do likewise? His plan is to address the “five As of sugar toxicity”. First is creating awareness of the addictive nature of sugar. Second is to alleviate stress in ways other than a sugar hit – sugar is a reward for the brain, but so are other things like exercise, a good deed, a favourite playlist, or a comedy on TV.

Third comes accessibility: sugar products are everywhere, including at supermarket check-outs. “You walk into a service station and you’re confronted with a wall of confectionary, even at office supply stores,” he laments. He has spoken with Australia Post, Foodland, Woolworths and other businesses about changing that, and is hopeful.

Next is addition – in other words, be aware how much added sugar is in what you buy, as it is often not clear on the packet. Up to 75 per cent of food and drinks have added sugar. Fifth comes advertising: “It’s everywhere, and can be insidious,” he says.

Muecke wants the government to become more involved and accountable. After all, the cost of Type 2 to the health system was estimated at $15 billion a year back in 2012. Australia should follow the UK’s lead with a traffic light system of food labelling, with high sugar given a red light, he says. But the government rejects this approach.

“The government could mandate to remove ads for sugary food and drinks from kid’s TV and from public facilities,” he argues. It could also tax highly sugared products. “We know there’s a link between sugar sweetened beverages and the development of Type 2 diabetes, but there’s also evidence that putting a levy on such drinks will reduce consumption – in Mexico and some US States they have done that.”

And finally, he argues, we need to see hard-hitting commercials featuring people like Neil Hansell on prime-time TV. “All these things worked for smoking, which is on the decline in most countries,” he says.

Muecke knows the lobby groups behind confectionary and soft drinks, as well as the sugar industry itself, will do everything they can to shoot down his arguments.

“There are a number of things I’d like to see in place before then end of the year,” he says. “First, to have Neil’s story out there, to turn around this terrible statistic of more than half of Aussies with diabetes not having their eye checks. Second, to see sugary products taken away from checkout counters. Third, to remove ads from kids’ TV and public spaces. And, finally, to have a comprehensive awareness campaign on free-to- air TV. Then I would feel that I’ve had a successful year.”