A tale of two cities’ art: London’s Pre-Raphaelites vs Paris’ Impressionists

They were two very different art revolutions based in Paris and London, but the common theme was a disdain for convention — and the famous results are now on display in Australia.

They were new, radical — and radically different — styles that shook up the art world, each in its own way a rebellion against claustrophobic 19th century convention.

On one side of the English Channel, the British Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) put a modern spin on their homage to a distant past; on the other, the French Impressionists set about capturing the fleeting moment without passing judgment.

Now, some of the finest examples of both movements have landed in Australia from two of the world’s most famous galleries, the Tate in London and The Hermitage in St Petersburg, offering a rare insight into two very different artistic rebellions in a world that was shifting through industrial to social and political revolution.

The Australian National Gallery in Canberra has opened its Love & Desire exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite Masterpieces from the Tate, which includes some of the gallery’s most famous canvases — including John Everett Millais’ Ophelia and John William Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott.

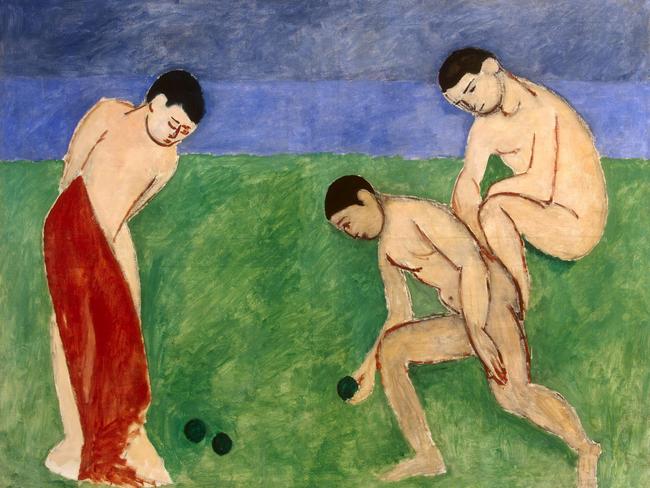

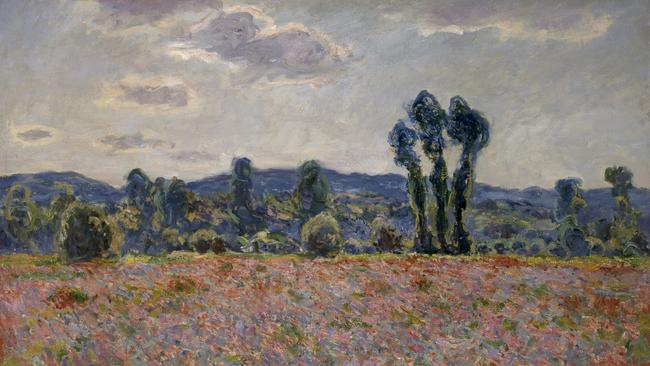

Meanwhile, up the road in Sydney at the Art Gallery of NSW, the Masters of Modern Art from the Hermitage is an extraordinary collection that sweeps from Impressionists like Claude Monet, through Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cezanne and into some of the early masterworks of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, and beyond.

Peter Raissis, curator of Historical European Art at the AGNSW, says it would be a treat to see both — the PRB began in 1848 and the Impressionists in the early 1870s — “one will illuminate the other”.

“The Pre-Raphaelites were really from the mid-19th right up to the 1890s, when the original movement morphs into Symbolism,” Raissis says. The young British painters were protesting against British traditional art, and even though they admired Italian painting from 400 years earlier (before Raphael), they were considered the first British modern art movement, tackling subjects like love, marriage, heartbreak, and death.

But, says Raissis, the European modernists rejected everything the Pre-Raphaelites stood for. “It was naturalistic, realistic, truth to nature, it had story telling component, a moralising component, concerns with serious subject matter,” he says of the British.

“The Impressionists weren’t interested in telling stories, the narrative or moralising aspect of art … they wanted to capture a moment, without a past and without a future. Very, very, different. You can appreciate more keenly the nature of the radical break that we see in European art if you see the Pre-Raphaelites first and then see the Masters of Modern Art.”

But for South Australians who saw 2018’s Impressionism blockbuster from Paris’s Musee d’Orsay, might it be a little repetitive?

No, says, Raissis, for two reasons. First, while many art lovers go to London, New York or Paris, fewer make it to St Petersburg in Russia, home of The Hermitage, one of the world’s greatest museums.

“And in this exhibition, unlike other Impressionists shows, you see them in a wider context — as the pioneers of modern art,” he says. “We tend to forget the Impressionists were breaking in style and subject matter from early 19th century art. Critics and the public scorned them as childish and inept. But they were appreciated by (and influenced) other artists.”

The collection from Russia is certainly extraordinary, not only for its works but the story of how they were collected — chiefly by two Russian industrialists, who became champions of the new French modern art movement, filling their palatial homes with some of the finest works.

Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov were frequent visitors to Paris and showed exceptional judgment in their selections. Shchukin in particular shifted from someone who was buying to impress others to a prescient collector who helped foster the early careers of Matisse and Picasso.

“They were enamoured of the cutting edge, avant-garde art from Paris,” says Raissis. “They began conventionally, moved to Impressionists, and then got more and more interested as the new century began, in the more innovative, progressive and artistically advanced painting …. they were collecting Gauguin, van Gogh and Cezanne, the Post-Impressionists. And Shchukin in particular … he was really the first collector to appreciate the qualities of artists such as Picasso and Matisse long before they’d made their mark in the rest of Europe.

“He famously amassed an enormous collection of Matisse and Picasso … by World War I, which brought an end to the collecting. He had 38 canvasses by Matisse and 50 by Picasso. He was collecting at a time when Picasso was just an unknown Spanish artist working in Paris.”

Raissis says two paintings commissioned were arguably Matisse’s great masterworks — Dance and Music of 1910. Shchukin got cold feet though because the works had nude figures and he worried how Moscow society would react, especially since he had an adopted daughter in the house. He asked the artist to make the 3m Dance panel smaller so he could fit it into his private bedroom, but Matisse refused. Later, Shchukin painted over the genitalia himself, and Raissis says only relatively recently was that revealed after conservation work.

Both collectors fled Russia after the 1917 Revolution, and while the works were displayed for a few years, under Stalin they were taken down as anti-Soviet and there was concern some may be destroyed. However, they were held in storage, and only began to emerge in the 1960s, before the rest of the world started to see what Russia had after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The Pre-Raphaelites were also vilified early in their time, and also had a champion — British critic John Ruskin.

The leaders of the movement were Dante Gabrielle Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais who met as students in 1848 at the Royal Academy. There were seven in the brotherhood, plus model Elizabeth Siddal and the poet Christina Rossetti, and the name comes from their rejection of the art style of Raphael, embraced at the time, in favour of works of Italian art in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Despite having a vastly different style and purpose to the Impressionists, there were some similarities. The National Gallery of Australia’s senior curator for international art, Lucina Ward, points out that among the radical elements were a willingness to paint outside — en plein air is usually associated with Impressionism — and focus on their own country and countryside, working with brighter colours, new pigments and light.

The play of the sun on the water in John Brett’s 1871 painting The British Channel seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs, for example, is something Monet might have enjoyed.

Ward says it’s relatively recently the Pre-Raphaelites have been seen as rebels, because the fact they were pictorial marked them to some as conservatives. But they were “radical because of the approach they’re taking to subject matter — they are insisting on the modern, the real, scenes of everyday life,” she says. “They are some of the first artists to spend a lot of time painting outside. Their approach to nature, taking nature as your teacher … is incredibly influential.” One of the biggest impacts was on decorative arts, and the 19th century’s most influential designer William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement, whose handmade approach railed against the industrial age, and included textiles, ceramics and elaborately printed books.

That social commentary is demonstrated in one of the paintings in Canberra, Work by Ford Maddox Brown, a large piece with working men, Potato Famine refugees from Ireland, an orphan, possibly a prostitute — a moral and social commentary on class and labour in the period. On the other hand, John William Waterhouse’s T he Lady of Shalott seems less radical — a beautiful woman in a boat. Yet even this, says Ward, can be seen as a commentary on the emancipation of women. The Lady is usually pictured trapped in her tower where she can only view the world through a mirror, for fear of invoking a killer curse. “Waterhouse’s emphasis on the solitary figure in a landscape suggests the Lady doesn’t care about the curse, it’s freedom at all costs,” she says. “The implication is she will die soon, but she’s casting off …” ●

Masters of Modern Art from The Hermitage, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, until March 3.

Love & Desire, Pre-Raphaelite Masterpieces from the Tate, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, until April 28.