A nation without Down syndrome?

PRENATAL testing is driving an increase in terminations of Down syndrome babies around the world. Critics say this push for perfection is not a health precaution, but eugenics in action.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

C HARLOTTE Roach is five years old. A little blonde bundle of energy wrestling on the couch with her older sister Alyssa one minute, sitting with brother Bailey in rapt attention in front of the TV the next. Your regular five-year-old then. With one difference. Charlotte has Down syndrome.

There are an estimated 1000 South Australians with the condition, and around 15-20 babies born with it each year in the state.

But an important ethical question is brewing about the way Western societies deal with Down syndrome, a condition marked by an extra chromosome, some distinctive physical features and a variable level of intellectual disability. It is predicted that soon in some countries, such as Denmark, there will be no more children born with the condition as the accuracy of prenatal testing and the rate of terminations increase.

In Charlotte’s case, the first sign she may have had the syndrome was discovered at a regulation 20-week scan. At that stage it was just one of a number of possible abnormalities. Mother Samantha and father Daniel were sent to a see a specialist paediatrician to talk about their options.

The scan was on a Wednesday but it was not until the following Monday they could see the specialist. “You try not to Google everything but you can’t help yourself,” Samantha says. “It was a long weekend.”

Samantha is grateful the paediatrician was neutral, not pushing them one way or the other. That is not always the case. Another specialist they say “read from a textbook from the ’60s” and gave outdated information.

But after that first meeting, Samantha and Daniel decided not to have any more tests done and to continue with the pregnancy.

“She instantly respected our decision when we said we weren’t interested in termination and moved straight on,” Daniel says.

But at 28 weeks, Charlotte needed fluid drained from her lungs in utero and while the procedure was taking place, Samantha also had an amniocentesis — in which a needle extracts fluid from the amniotic sac surrounding the foetus — to check the prospect of Down syndrome.

“We always had it in our heads,” Samantha says. “Being told, even though you have it in your head that it’s a possibility, when you are told it’s like being hit by a bus.”

But there were no regrets either.

“By that stage we were looking forward to meeting her and certainly didn’t want to terminate — particularly at that late stage,” Daniel says.

Down syndrome was first described by a British doctor in 1866 and affects six million people worldwide. But there have been significant advances in recent decades with life expectancy more than doubling, with many getting married, holding jobs and enjoying full lives.

Research has found these people, who are born with an extra 21st chromosome, to be among the most satisfied in society with their lives and looks, bringing joy to family and friends.

But crusaders such as biologist Richard Dawkins claim it is “immoral” to bring such children into the world if scientific advances offer choice. “Abort it and try again,” he told one woman struggling with the issue.

Other academics have even raised the shocking spectre of terminating babies with Down syndrome after birth, arguing they might be happy individuals but are an “unbearable burden” on families and state resources.

Daniel Roach is disgusted with the “eugenics” world view propounded by people such as Dawkins.

“What is says to me is that they are not even worth being born and that is a very hard line approach,” he says. “That sort of theory has been popular in the past. Look at Nazi Germany and where that got us.”

And, he says, if you start with Down syndrome where do you end?

“There is a whole bunch of complications that can occur after birth or during birth that can be far worse,” he says.

“It’s like saying, ‘you suffered this brain injury, well we could have terminated you at birth, why don’t we just euthanase you now?’ How far do we want to go?”

Daniel and Samantha limited the news about Charlotte to only a few close family and friends. They didn’t want Charlotte to be only defined by her Down syndrome.

“If people were labelling her before they ever met her, that is all the would ever see,” Samantha says.

It’s that labelling that most bothers Charlotte’s parents. The myths and the stigmas that surround the condition are mostly based on an old-fashioned perspective of what people with Down syndrome are capable of accomplishing.

“It’s easy to pick because of facial characteristics so people think they know about it in society,” Samantha says. “I think that’s why it’s targeted.”

“I think the biggest issue is because they have a diagnosis it’s really easy to pigeonhole them,” says Daniel. “The more we have been involved in the (Down syndrome) community the more you realise you can’t pigeonhole.”

Ellen Skladzien is the chief executive of Down syndrome Australia and says one of the biggest problems facing parents of children who may have the condition is the lack of knowledge, not just in the community but in the medical fraternity.

“What we have is doctors telling families their child will have a lifetime of suffering or they will never go to school or it will be devastating for their marriage,” she says. “We know all these things are untrue.”

In the 1970s the average life expectancy for someone with Down syndrome was around 25. Now people are living into their 60s and 70s. The role of Down syndrome Australia is to better inform doctors and to bring together families affected by Down syndrome to help each other and share knowledge.

Charlotte Roach has been to mainstream child care, mainstream kindy, mainstream dance classes and will start mainstream school later this year.

The number of babies born with Down syndrome is hard to pin down in Australia. There is no national register. But there is evidence elsewhere in the world that the birth of a Down syndrome child is increasingly rare.

The most recent figures available in South Australia are from 2013. That year, prenatal screening picked up 64 cases of Down syndrome. Of those, 48 pregnancies were terminated and 16 proceeded to birth. A termination rate of 75 per cent puts South Australia in line with nations such as the US and France.

By comparison, in 1988 in SA only 21 per cent of the 28 Down syndrome cases were terminated. The ratio had risen to 74 per cent by 2003, but the number of diagnoses (and therefore terminations) had also increased markedly as more women over the age of 35 became pregnant. The older the mother, the higher the risk.

In future, as testing becomes increasingly sophisticated, it is likely that more and more Down syndrome pregnancies in Australia will be terminated.

In Britain, a new blood test — Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing — which offers simpler and more accurate screening for Down syndrome and some other abnormalities is being rolled out across the National Health Service.

It has provoked the Church of England to warn the existence of people with Down syndrome is “under question”. Already, the United Kingdom terminates around 90 per cent of Down syndrome pregnancies, while in Iceland and Denmark it is now close to 100 per cent, with predictions that soon no more children with the condition will be born.

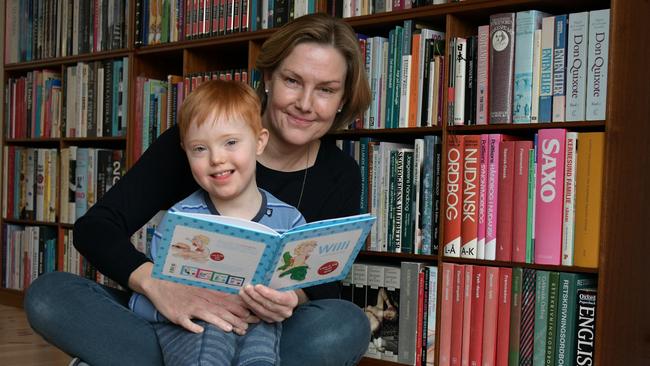

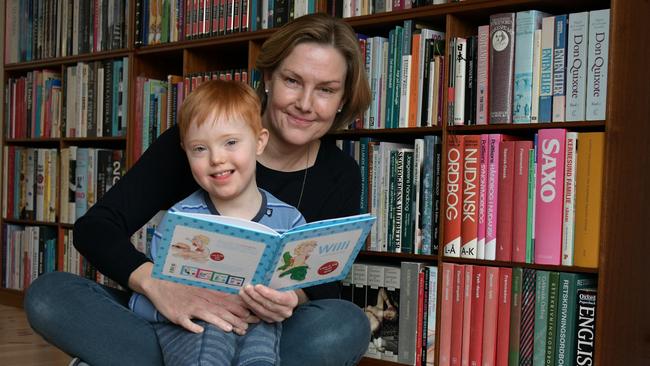

It’s a tough challenge for any parent. Erica Gaarn-Larsen, from Denmark, says she probably would have aborted her son Philip if the scans had picked up the abnormality.

“I did not want a child with disability,” the 47-year-old concedes. “I thought my life would be changed and maybe even ruined. I had no real knowledge, just the feeling this would be something terrible.”

She only discovered the second of her three children had a learning disability after his birth. “I had 24 hours of going through hell thinking, ‘Why did this happen to me?’ ” she says. “But then I looked at my lovely little baby and decided we could handle this. Now I can think of 100 things worse in life than having a disabled child.”

The Scandinavian country is close to the world leader in eliminating the condition. In Denmark there were 80 born with Down syndrome in 1999 — but by 2016 the number had fallen to just 24.

Of those, only four were born after positive prenatal diagnosis. The Scandinavian nation has the world’s highest termination rate in such cases, with 98 per cent detected in the womb aborted. As mentioned, that is likely to rise with more accurate, less risky testing.

Denmark now faces the real possibility that it could become the first nation to wipe out Down syndrome altogether. And others are likely to follow.

Denmark is a decent, open, sophisticated nation. Yet its experience shows, some critics say, we are sliding into a new age of eugenics with scarcely a murmur of dissent and minimal discussion of ethics, morality or the complex meaning of humanity.

“We are moving towards eliminating Down syndrome and some other disabilities,” says John Brodersen, professor in public health at the University of Copenhagen. “There’s no doubt this is eugenics.”

Over the past three years, only eight of the 407 Danish cases detected in prenatal screening survived to birth. Another 83 children with the syndrome were born after false-negatives, such as Philip, or because their parents rejected testing.

Like Ellen Skladzien in Australia, Brodersen blames the medical profession for painting too stark a picture for parents as they confront the prospect of life with a disabled child.

“Parents want a perfect child and the medical profession is encouraging them,” he says. “They present a very black and white case, but even within Down syndrome people are different. Yet they are being seen as monsters, far from human beings.”

He argues that as numbers plummet, tolerance declines. “They are more likely to be regarded as aliens,” he says. “Today when people meet a child with such a disability they wonder why was it not terminated or was there a technical mistake.”

This is tough moral terrain. Some believe women should be able to choose an early abortion, just as photographer Line Holm did last year after it was confirmed that her 12-week-old foetus had Down syndrome.

“I was in shock and crying but I knew right away I was going to have an abortion,” says Holm, 40, a mother of two boys from Viborg in Jutland, Denmark.

Unlike many people, she had some insight, having worked on a documentary about people with the condition. “I knew it would make a big impact on my family for the rest of our lives and on my children when I am no longer here.”

Holm has no regrets. Yet where is the debate over the collective impact of rational individual decisions as they weed out people that add to the diversity of humankind?

Denmark is in the vanguard of this brave new world since it has a liberal approach to abortion, partly due to historically high female participation in the workplace. Polls show majority support for terminating foetuses indicating Down syndrome.

Any woman in Denmark can terminate a pregnancy during the first 12 weeks, then for the next 10 weeks if agreed by special regional boards that there is a chance of serious mental or physical disorder, which is deigned to include Down syndrome.

Ann Tabor, professor of foetal medicine at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, counsels many couples in this situation. “Most are just so sad and angry that something is not normal,” she says. “They come in expecting a scan picture for the fridge and suddenly they do not have the perfect child they expected. Most parents want a normal child. We know the IQ [of Down’s children] is considerably less than that of a normal child. They are not such a big burden when small but can be difficult as teenagers and beyond. They do not have such a big impact on society.”

She denies high termination rates mean people with Down syndrome are less valued — although she accepts that in a “perfectionist society” there is less space than in the past for people displaying such differences.

Eugenics is now a shamed concept. A century ago, academics and writers debated ideas of eliminating human “deficiencies”, theories that led with dreadful logic to the Nazi death camps. Yet almost three decades ago, Troy Duster, a farsighted New York sociologist, warned that science and genetics were unleashing a new era of eugenics through “screens, treatments and therapies”. Now this age is arriving.

When talk of mass testing began in Denmark late last century, there were even suggestions that it was cheaper to screen since it reduced the numbers needing care.

One senior doctor openly talks about the “cost-effectiveness” of screening, while others fear this still underpins the issue for politicians, including Lillian Bondo, head of the Danish Midwives Association, whose own sister Ida had Down syndrome. Bondo admits to being conflicted over this issue, agreeing that most parents “instantly” seek termination when faced with a Down syndrome baby and readily accepting that medical advances are improving lives.

But she fears we are seeing more children born with severe disabilities, especially when very premature babies are kept alive despite complications, while minor conditions such as Down are being “removed” by medicine.

“Society is creating some new handicaps while trying to root out others,” she says. “Perhaps we should establish a pain threshold based on suffering?”

She wants more recognition that people with Down syndrome lead valuable lives. “But when you are having only 25 people born each year, not 150, this means there is much less chance to meet such a child,” she says.

A few families with a Down syndrome child, feeling unwelcome in Denmark, have even fled to Norway. “The signal being sent is that society does not want people with Down syndrome,” says Lars Brustad, secretary of the Norwegian Network for Down syndrome.

“In my opinion this is a horror story. It is very difficult for parents like me to understand. There is no reason to offer these abortions when people with Down syndrome can live good lives.”

This issue reflects the lingering hostility towards people who are not “normal”. And such fears are exacerbated by the crushing fight for support that faces parents of disabled children in countries such as Britain and Denmark. Yet Brustad, a retired banker, believes the Danes are only being more open about this dawn of a new eugenics.

Copenhagen psychologist Line Natascha Larsen, 41, has a seven-year-old son, August, with Down syndrome. Larsen admits she and husband Max were sad when their child was diagnosed but she learned a key lesson from an adult with the condition. “He told me to believe in my child,” she says. “Don’t protect him but help him achieve everything he can.”

She has done just that. “August is so warm and loving, very funny and living in the present,” says Larsen. “Yet those people seen as a bit different can make some others uncomfortable instead of being embraced for enriching society.

“We are going to make our world so much more boring with this quest for perfection.”

Back in Seaford Downs, the Roach family is happy in the chaos that only having three children under the age of 10 can bring. Samantha and Daniel have the same hopes and dreams for Charlotte as they have for their other kids Alyssa and Bailey.

“In her 20s she moves out like the other two,” says Daniel. “I expect her to get a job, I don’t expect her to be reliant on other people. I expect her to learn to drive like the other kids, I expect she might get married. I don’t expect her not to do those things.

“It sounds silly when you say it, but you sort of forget she has Down syndrome most of the time. Basically she’s simply one of our kids — not really more or less special than the other two.”

© With the Mail On Sunday