A life devoted to ending domestic violence

TO win justice for herself and her children, SA’s Glyn Scott went to the High Court where she achieved change in Australia’s marriage laws. Now, at age 71, she’s a campaigner against domestic violence.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

GLYN Scott seems so soft in pink knitwear and sensible shoes, with a chain of butterflies around her wrist.

They signify hope and freedom, the 71-year-old says in a quiet voice that belies an inner steel, and a life transformed through its own dramatic metamorphosis.

As a young girl she was traumatised by rapes and beatings so severe it is a miracle she survived them. In later life she made legal history by winning a High Court decision that the fact the accused rapist had been her husband gave him no immunity.

And now she is a fierce campaigner who has vowed to devote the rest of her life to seeing domestic violence stamped out.

She could have tried to run from traumatic memories, but she has not. Instead Glyn has established the Love, Hope & Gratitude Foundation, and penned an autobiography, Hope Was All I Had. Due next month, it’s a story of horror that comes at a time of a growing national consciousness of the scale and consequences of domestic abuse.

She started writing it after her second husband, Lance Scott, died in 2003. “I made him a promise that I would write my story, when he was dying,” Glyn recalls. “It was a long journey. Sometimes I had to stop and go back to it later because it was very difficult to write, because it brought it all back.”

The work is self-published. Some editors loved her account – it brought them to tears – but thought it too confronting. Did she consider toning it down? “No. It’s about the real story, telling the story how it actually was, not glossing over stuff,” she says.

The real story is certainly harrowing. Born in 1945, Glyn was abandoned by her mother and spent time in an orphanage before being adopted by a church-going couple from Alberton.

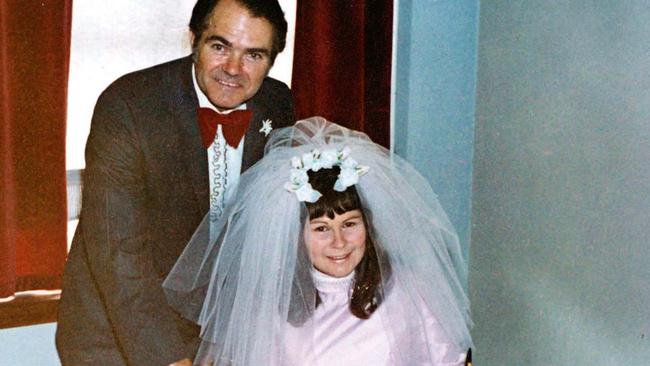

She was sexually abused throughout her childhood, firstly while in the orphanage and then by a Sunday school teacher. In 1962, aged 17, Glyn fell pregnant and married the father – a predatory giant of a man named George Pycroft who she says raped and beat her incessantly.

Why did no-one intervene? “All through my whole life right from day one, I’ve fallen through the cracks of all government departments, the church, the orphanage – all services, because, well, I was a complete nobody and nobody really cared,” she says. “I never understood why. But no bugger ever stood up for me.”

Glyn talks of one beating when she was left with broken bones and teeth, bloodied and bruised, naked in the driveway. The rapes continued on a daily basis throughout their marriage including the day she returned home from hospital after giving birth to their first son, Stephen.

Glyn’s second baby didn’t survive the brutal bashing she received just days before going into labour. “He wasn’t stillborn,” Glyn insists. “I hate it when people say that. To me he was murdered and I’ll never change that view because he beat me so badly the baby was macerated.” Soon after she had a third child, a girl, about whom she claims Pycroft said: “I’ve finally got a daughter, and no bastard’s having her before I do.”

Glyn divorced Pycroft in 1971. Many years later she reported the abuse to police but describes their response as negative. It seems that while attitudes to violence against women had begun to change by this time, the law had not.

But in 2006, more than three decades after her divorce, life changed dramatically for Glyn. With the support of her doctor she provided details of the sexual abuse she suffered since early childhood to former judge Ted Mullighan QC, head of the inquiry into sexual abuse of children in state care.

From that point the police were strongly on board and the wheels of justice began to roll. The Mullighan Inquiry heard Glyn’s allegations of sexual assault while in state care by the orphanage, the Sunday school teacher and George Pycroft. The police charged Pycroft with six offences occurring in 1963, the year in which medical and eye witness evidence was surprisingly still obtainable. This evidence, along with Glyn’s accurate and consistent recall of events, aided the Director of Public Prosecutions to determine that the matter had a reasonable prospect of conviction, in 2009.

“That any key witness is one whose evidence a jury can accept as reliable and credible is always an important consideration in determining whether there is a reasonable prospect of conviction,” says the DPP, Adam Kimber SC. “Ms Scott was assessed as a witness the jury could accept as reliable and credible.”

But an historic law had to be argued in the Australian High Court in order for the case against Pycroft to proceed. If a husband raped his wife in 1963, was it a crime? Perhaps not, because it was believed marital exemption was part of common law in those days. This was an historic notion based on a belief that a woman gave ongoing consent to sexual relations once she was married.

On the day that Pycroft dragged Glyn, raped and badly beaten, on to their driveway her neighbours rang the police. “When they came I couldn’t walk, there was blood everywhere … but I was married to him so the police couldn’t intervene,” says Glyn.

Pycroft’s lawyers argued he would never have been charged with rape back in 1963. Certainly there was weight to their argument as Pycroft was never charged, despite the police witnessing the severity of the abuse. Legal argument ensued: even if Pycroft had been charged immediately after the offences in 1963, would he have been prosecuted? Most likely not, because of the belief at that time that the crime of rape could not be committed by a husband against his wife.

But, almost a year after it heard the case, the High Court in 2012 ruled in a 5-2 history-making decision that if marital exemption to rape was ever part of common law in Australia, it ceased to be when the Criminal Law Consolidation Act came into effect in 1935. This decision paved the way for all victims of sexual abuse within their marriage since 1935 to come forward and pursue justice.

Unfortunately for Glyn the wheels of justice ground to a halt not long after the decision was handed down, because Pycroft died, aged 82.

“I felt cheated,” explains Glyn. “And my daughter particularly – she wanted to face him in court. And I was surprised, because she’s very much an introvert but she wanted to see him held accountable in court for what he did to all of us. She still says to me, ‘Mum I feel totally cheated. That bloody arsehole died before we could get there’.”

While victims have varied reasons for pursuing prosecution of their perpetrators, for Glyn it was never about revenge: “Revenge to me is a very dangerous thing. And I thought what does revenge do? It doesn’t achieve anything and sometimes it causes more pain. Yes, I wanted him to be accountable for what he did to us, but I certainly didn’t want revenge in any way.”

Perhaps it’s not revenge by definition, particularly not against Pycroft, but Glyn has certainly launched a war against all abusers, taking back power and control by working tirelessly as a campaigner and an advocate for victims of domestic violence.

An active and public campaigner she may be, but Glyn describes herself as very private and extremely shy. On the subject of her perceived resilience and strength Glyn says, “People say to me, you know, you’re such a strong person, but inside I don’t feel strong. Underneath, I don’t feel strong. But my focus is more on making sure that I stay strong for others. I have to push myself to do what I do, but I do it for them.”

Although she finds it hard, Glyn hopes that sharing her experiences encourages others to speak out and seek help and protection from domestic violence. While the DPP’s statistics don’t differentiate between incidents of assault or sexual assault that occur within a domestic environment to those that don’t, Adam Kimber SC believes that domestically perpetrated assault cases are reported more commonly today than a few years ago.

“This office does not collect relevant data, but my sense is that this is a consequence of, among other things, greater recognition that such offending occurs and better supports being provided to alleged victims when they come forward,” he says.

Whilst she’d like this to be true Glyn is sceptical, believing that any increase in reporting is actually a reflection of the increasing number of incidents, likely caused by the growing problem of drug-induced assaults.

Statistics on domestic violence-related assaults are difficult to gather, as assaults are often unreported. “It’s about the fear and the guilt and the shame,” Glyn explains. “There are also a lot of people in high profile places – they may drive BMWs and the kids go to private school – but they’re getting the crap beaten out of them every day. The men are bloody clever. They freeze the joint accounts and the women have nothing. And the reason I know this is because they come to me. They say they can’t tell anyone else. Power and control is at the base of all domestic violence. That’s what it’s all about.”

Evidence gathered by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in its 2012 Personal Safety Survey showed 95 per cent of men and 80 per cent of women experiencing violence from a current partner had never contacted the police. Despite this, based on information available, the Foundation states that throughout Australia two women die through domestic violence each week and one child each fortnight. “It’s rife,” says Glyn.

I suggest that after such a traumatic life one might expect Glyn to spend her retirement years doing something far more pleasant. She admits she imagined her retirement to be quite different. “I never thought about anything like what I’m doing now. I thought my retirement would be, well, I’m very creative and so I just thought I’d make things and I’d look after animals. I’m very passionate about that, and I just enjoy nature. I never really thought beyond that.”

Instead, she is a trained counsellor and advocate specialising in domestic violence, child abuse and homelessness.

Last year, she established the Love, Hope & Gratitude Foundation and has a team of 22 core volunteers working to provide shelter, comfort and support for women, children and their pets requiring a safe haven from abuse, abandonment or hardship. Recently the Foundation held its inaugural Butterfly Walk and Family Fun Day, raising awareness and more than $2000 for their campaign.

She intends to establish support groups for women involved in adoption and fostering because of her own background and also for the homeless, a topic she is passionate about. She wants to write a self-help book. In order to fit that in I suggest she may have to give up sleep. “I already have,” she responds. “I only sleep two to four hours a night.”

Glyn has worked with homeless people for the past three years. “Mostly from the beginning it was older men but then I started meeting up with young kids, some as young as eight, but they would hide because the situation is very difficult for them – 90 per cent are being abused at home and neglected and they couldn’t cope any more,” she says.

“They hide because the police take them to Families SA or return them home – but that’s just putting them back into a system that abuses them, so they keep running away. They don’t trust anyone.”

Counselling kids who have nowhere to go is challenging. “I ask them if there is anyone they know (to stay with). Usually they do know someone but they’re frightened because that person might tell their parents and then they’re back in that abusive cycle. So I always give them my mobile number and I say, ‘If you need help, you only have to ring me and I will do whatever I can ... food, clothing, blankets ...’ I want to build a shelter for them, too, but councils aren’t on board.”

The shelter would be for domestic violence victims, their children and their pets. Her ultimate vision is a gated community with cabins or small houses, a playground, a community centre and a medical centre. She is exploring options with respect to land. “It would be temporary accommodation, say for 12 months, so they have a chance to rebuild their lives,” she explains. Having moved 17 times in five months attempting to hide from Pycroft, Glyn knows better than anyone the need for security, confidentiality and safety.

“There is no point hiding, because they’ll be found eventually.”

How will the foundation achieve all this? “We’re working hard to raise funds and we have some people who can donate time and resources. We will explore options for grants. And I’m looking forward to working with other services to complement what we do,” she says. “That’s what my vision is. In the meantime, we’ll do whatever we can to house as many women as we can so that they are looked after and safe. I’m not one to give up.”

She fiddles with the butterfly bracelet on her wrist and says, “I’m a fighter. I see so much cruelty and trauma that I will not stop. I want this to be a legacy that I can leave when I go, that can continue forever.”

Hope Was All I Had, available December 8, $32.99, from Dymocks Rundle Mall; glynscott.com.au; lovehopeandgratitude.org.au

Adelaide White Ribbon Breakfast 2016, November 25, 6.45am-9am, Adelaide Convention Centre, with keynote speaker Marcia Neave AO – Chair of the Royal Commission into family violence, $60/$35, trybooking.com/MOJG

If this story raises issues and you need to talk, call the National Sexual Assault, Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service 1800 737 732 (24/7)