Should Australia follow Canada and 11 US states to legalise recreational cannabis? Supporters say it would cut crime and help control the drug, but critics say the risks for young brains is too high. HAVE YOUR SAY AT CONCLUSION OF THE ARTICLE.

He walks into the café in a business suit, well-groomed and smiling.

He looks about 30. This is not the appearance of a man that has spent nearly a decade unemployed, a daily user of cannabis for nearly half his life.

This is a man who has pulled himself back from the brink.

Adam was a good student with a close group of friends when, at 15, his older brother introduced him to the drug.

By 18, in his first year of university, cannabis was a daily habit, helping him to relax at night. Before long, he’d suffer cravings if he didn’t have it.

At its height, he would smoke 20-30 bongs (water pipes) a day — a lot of mind-altering impact from the active ingredient, delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Unmotivated, he dropped out of university for a job at Subway.

He would never go back.

Adam, of Norwood, had always been sociable. With the drug, he preferred to stay home and smoke. Soon friends stopped inviting him out. Crowds became a source of fear, and he began to suffer panic attacks at the thought of being near any, even to watch his team, Adelaide United, play.

Then, when Adam began taking ecstasy, he started missing shifts at Subway, and lost his job.

Professor Michael Baigent of Flinders University, psychiatrist and addiction medicine specialist, has heard many stories like Adam’s.

He knows what can happen when adolescents become reliant on cannabis.

“The more entrenched it is in their social network, the less engaging opportunities they have, the more likely it is they will become dependent on it,” he says.

“The trajectory for these young people is much more concerning as they are then likely to continue their drug use, and this can lead to trying other drugs.”

Australians are among the highest users of cannabis in the world, with about 10 per cent of people using it regularly and about 4 per cent of 15-19 year olds using it weekly.

And, as the drug becomes increasingly legalised overseas, calls are likely to grow for a similar approach here. Canada has legalised the drug, arguing it will keep drug profits out of criminal hands, and so have 11 American states.

The question is, does that approach create as many problems as it solves?

Adam’s experiences were not unusual for a long-term frequent cannabis user. Drug dependence, lack of motivation, anxiety, panic attacks, depression, and social phobia have all been linked to frequent and heavy cannabis use.

Research has also been building over the past 20 years showing a risk of more serious mental health issues associated with cannabis use and those working in mental health are worried. Recent research has pointed to particular impacts on developing teenage brains.

The overall effects of the drug can include psychotic episodes leading to a later psychotic disorder (losing one’s sense of reality) or a type of psychosis, schizophrenia.

Researchers are investigating, but it is not yet clear how this association comes about.

Alex Berenson, a former New York Times journalist and author of the book Tell your Children: The Truth about Marijuana, Mental Illness and Violence is concerned that the relentless march towards legalisation ignores serious health risks.

He argues attitudes in the US have been influenced by the companies responsible for manufacturing medicinal cannabis, deliberately confusing people into believing that it is a medicine rather than an intoxicant.

Confusion has hit Australia too by the recent legalisation of medicinal cannabis (for certain medical conditions) and industrial hemp (seed for food and fibre for clothing).

But as Baigent, psychiatrist and addiction medicine specialist of Flinders University explains, the ingredients are not the same. That part of the cannabis plant used for those products contains very low levels of THC and has none of the mind-altering and potentially damaging effects of the drug found in the flowered part of the cannabis plant, the part that remains illegal for recreational use in Australia.

This belief that cannabis is harmless is probably a throwback from the baby boomer generation who are now the parents of those aged 18-25, the ones most likely to try the drug.

But as Berenson says (and Baigent agrees), THC levels are higher than before due to the hydroponic processes available now, about 20 per cent up on 20 years ago.

He compares the difference to that “between a beer and a martini”.

Berenson argues that a review conducted by the 2017 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found that cannabis can cause psychosis and schizophrenia.

His critics are outraged by what they say is an exaggeration. Most notably, one of the report’s own authors, Ziva Cooper, has criticised Berenson’s view for being dangerous and misinformed.

She clarifies that an association between cannabis and psychosis has been found but that there is not enough evidence to show that cannabis is the cause.

Berenson also suggests a link between psychotic conditions and violent crime.

He supports his claim by pointing to a sharp increase in crime in the first four US states that have legalised the drug.

One critic, Chicago Lewis, a writer for Rolling Stone magazine, suggests this attempt to link the two is like saying that increased availability of organic food leads to autism, considering the increase in both.

She claims that it is the illegality of cannabis that is causing the most harm through violent crime associated with its illegal manufacture and sale, and by the lack of regulation in how it is manufactured.

Much about the drug is unknown.

Writer Malcolm Gladwell who reviewed Berenson’s book in a New Yorker article in January this year, notes that although Berenson might have overstated the case, the governmental approach across the US towards liberalising cannabis is surprising when we know so little about it.

He compares it to the approach taken towards a new pharmaceutical drug.

“Figuring out the ‘dose-response relationship’ of a new compound is something a pharmaceutical company does from the start of trials in human subjects … the amount of active ingredient in a pill and the metabolic path that ingredient takes after it enters your body — these are things that drugmakers will have painstakingly mapped out before the product comes on the market …”

In comparison, Gladwell notes that we are still waiting for this information about cannabis.

On one point, at least, everyone agrees — more research is needed. Where they disagree is whether we should know more about cannabis before we take the jump into the unknown abyss of legalisation.

Matt Noffs, chief executive of the Ted Noffs Foundation in Sydney, says Australia led the way in better controls over tobacco sales, and needs to get ahead on cannabis, since the pressure for legalisation will grow.

“I am not for legalising cannabis without more control,” he said recently. “I am for more control and right now. When it comes to cannabis in Australia, we have very little (control).”

Noffs argues that Australia has managed to reduce tobacco use despite it being legal by sale restrictions and plain packaging, so “let’s do the same for cannabis,” he said in an opinion piece for the ABC.

In South Australia, Baigent — who has treated people with mental health issues and addiction over 30 years — believes we know enough that we should limit the drug’s availability. He is comfortable with the way things are currently in this state, namely decriminalised for personal use but a criminal offence to manufacture it.

“I wouldn’t like to see it liberalised any more than that because of the clinical harms that I see from its use. Research indicates that where it is more available, there is increased use. It’s not an innocuous drug.”

Adam is sure of that. After losing his job at Subway, things got steadily worse. He would remain unemployed for the next eight years, suffering extreme anxiety which presented in the strangest forms.

Adam had moved into the granny flat on his parents’ property, which triggered a need to be houseproud. That turned into an obsession. He spent most of the working day cleaning both his own flat and his parents’ entire house. Cleaning dictated what Adam would be able to do for the day. It got to the point where if anyone even opened the door, he would visualise dirt coming in and he’d have to start again.

A feeling of utter devastation would overwhelm him if he was unhappy with the job he had done.

The introduction of methamphetamines into his life tipped Adam over the edge. It made all of his bad feelings worse and his cleaning obsession intensified.

“I would get really upset and then tell myself that I had to wipe something four times, then question whether I even did that and do it another four times, a different way. It was a lot of that sort of stuff,” he says.

He felt a lot of anger, his skin looked terrible and he lost weight. And then he stopped taking it. No rehab, no detox, just his own resolve.

I pretty much woke up one day and thought, ‘I’m done with this’,” he says.

“I just thought to myself, ‘I’m so sick and tired of this, the horrible feelings that you have, the way it makes you look’.”

He continued smoking cannabis for another couple of years and then stopped.

He remembers the day. January 26, 2015. Although he had been to detox centres on numerous occasions at the request of his parents, this time he submitted himself to detox at Glenside and never took it up again.

He smoked a lot of cigarettes during that time but gave them up too the next year. Why?

“I was jealous,” he says.

“I was jealous of my friends. They were getting engaged, they were going away on trips. I knew I’d been falling behind for a long time but I was the last one. I had been for a few years.”

The combination of Adam’s age when he began using cannabis and his daily use made him especially vulnerable for problems.

A 2014 Australian study conducted by the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, (accounting for a wide-range of other factors that could affect development) found that people who began using in adolescence, by the time they turned 25, were three times more likely than their non-using peers to drop out of high school or university, seven times more likely to attempt suicide, 18 times more likely to be cannabis-dependent and eight times more likely to go on to use other drugs.

Professor Patrick McGorry, psychiatrist at the University of Melbourne and a former Australian of the Year for his services to youth mental health, has seen that cannabis can have particularly serious effects on the mental health of vulnerable people.

One of the major factors of vulnerability is youth.

An Australian research study conducted on siblings in the ’80s found that adolescents that start using cannabis at 15 or younger are twice as likely to develop a psychotic disorder than their non-using peers.

McGorry explains this level of risk as being much the same as smoking will increase the risk of having a heart attack.

After the age of 15, daily use is more clearly implicated. The Lancet Psychiatry journal published a study recently indicating that daily use of cannabis will raise the risk to three-fold in contrast to those who have never used the drug.

There may be a physical reason why the adolescent brain is more vulnerable as found last year by researchers at Swinburne University in Melbourne.

In adolescence, parts of the brain are pruned and there are consequent changes in neural connectivity. This latest study shows that adolescents who have used cannabis even just once or twice have larger grey matter than those who haven’t, indicating that this process of pruning has been interrupted. A link was also found between these changes in grey matter and effects on those individuals’ reasoning and anxiety levels. Research is ongoing.

Other than age, some individuals are simply more vulnerable than others to the drug’s adverse effects.

A report produced by McGorry and his team at the University of Melbourne, led by author Meredith McHugh, found that if people suffered a panic attack or other warning signs which worsened when using cannabis, they were more vulnerable to the risk of a future episode of psychosis or other long-term mental illness.

Factors such as serious childhood adversity, symptoms of anxiety, depression or panic attacks will also place a person in the vulnerable category for a future mental health disorder.

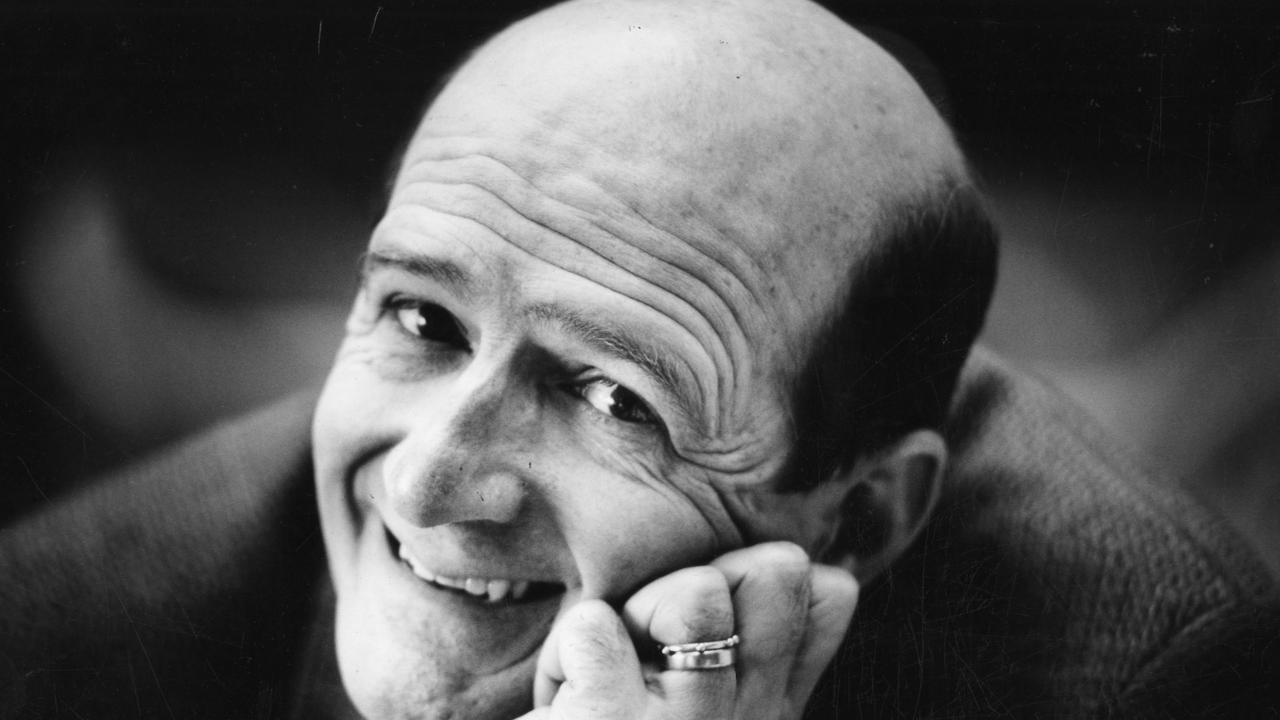

Garry McDonald, the well-known Australian actor and comedian, has publicly stated that cannabis was responsible for inducing his first panic attack, triggering his long battle with anxiety.

It is pretty clear that if young people are particularly vulnerable to such devastating impacts, early intervention should be a priority.

McGorry, who was the founder of the nationwide youth mental health service, Headspace, and is an executive director of Orygen Youth Health, promotes an early interventionist approach as the key to prevention of psychosis where a person is showing early signs of developing a mental health disorder.

“This young person might withdraw and change in personality, become less engaged in activities, their self-care will drop off, they might start behaving strangely, or discuss odd beliefs or question motives,” explains Baigent.

Yet Stephen, of Walkerville, father of Louise, 22, knows how hard it is to effect change if the person doesn’t want to.

Louise began smoking cannabis when she was 14 or 15.

She is from a privileged background with all the opportunities that go with that, but she faced some personal challenges with her parents’ divorce when she was very young and her mother’s second marriage breakdown when she was an adolescent.

Louise used cannabis when she was sad, which made her feel good for a short time, but the downside was bad.

She was soon dependent on the drug to make her feel better.

A school prefect and a straight A student, she began running away from home, dropping out of school at 15. Stephen and his ex-wife tried many times to sit her down with health professionals who would advise her to stop using drugs. She would be admitted for detox but as soon as she was out, she would be back using.

She still smokes cannabis when she can afford it and has also taken drugs such as ice, that are cheaper and more accessible, with even greater impacts on her health and stability.

The family can no longer live with her erratic and aggressive behaviour.

She has spent periods of her life homeless but Stephen is thankful that, for now, she has a roof over her head with the assistance of government housing.

He has long since stopped paying for her power bills or anything at all as she would rather spend the money funding her drug habit.

Stephen organised for Louise to attend rehabilitation several years ago when he thought she was making progress but she refused to go.

“She would rather self-destruct than get help,” he says.

“I don’t know what the answer is. I’d like to put her on an island somewhere away from everyone … I think one day the cops will knock on my door and say that something has happened. I feel totally powerless.”

Katrina, of Medindie, mother of Matthew, aged 21, is living with the same fears.

Matthew began smoking cannabis daily at 14. Although sensitive and perhaps less robust than Katrina’s other children, Matthew was a popular, high-achieving student who, like Adam, enjoyed sport. She noticed some changes to his personality at the time but she and her husband thought it was a teenage boy thing.

“We thought he would grow out of it but, in hindsight, when they start young, they never grow out of it.”

Matthew soon lost all motivation, losing interest in sport, social life and studying. By the time he reached the end of Year 12, “a kid that should have been sitting on an ATAR in the 80s or 90s, got a 56,” says Katrina.

He, too, tried methamphetamine and ecstasy but was able to stop them at least, with the help of his then girlfriend. Cannabis, though, remains a constant.

His parents, just like Louise’s, tried to get him into a rehabilitation centre in Adelaide. The health authorities there told them that they don’t accept adolescents unless they have hit rock-bottom.

Katrina was shocked but Baigent explains: “What I think we health professionals really mean by saying that, is that something needs to happen to help them form their own resolve. For some people, things turning really sour can make them see it for themselves and, for others, finding a new meaning in life, a new relationship or maybe suffering psychotic symptoms every time you use the drug is what it will take.”

Matthew is not there yet but Katrina, who feels she has tried every other approach to motivate him to change, is now using tough love in the hope he reaches this point.

Thrown out of home, he will be allowed back on one condition — that he agrees to accept help from mental health services to assist him to stop using cannabis.

In Adam’s case, it was jealousy of his peers that was enough to trigger his own resolve.

“I always knew there were things I wanted to do,” he says. “I always knew that I wasn’t where I could have been and that I wasn’t in a good place. I was taking drugs to mask that, which is the whole point.”

He knew he was over the pull of drugs when, later that year, he was invited along to a ski trip and, with his parents’ support, he went.

“That was big for me. I wasn’t going to be able to clean my house for a week, I wouldn’t be able to go home when I wanted to but I didn’t feel at all anxious, just excited,” Adam says. “It was the best holiday I’ve ever been on.”

That same year, Adam started work at a restaurant serving as front of house staff where he met the woman who is now his life partner. She encouraged him to do a TAFE course in business studies and when one of the big four banks was recruiting, he got the job. He now works full-time for them as their collection manager.

Newly engaged, he enjoys the work, has been overseas twice, and has more money than he’s ever had. He is not tempted to try drugs again even when he has a bad day. These days watching a DVD is enough to relax him. He knows that he lost years of his life where he might have otherwise got his university degree and a higher paying job.

But he is fatalistic. He feels lucky to be a survivor. He feels lucky to have had supportive parents who have allowed him to stay at home in a safe environment, knowing how difficult it was for them to see what he was doing and not being able to stop it. In retrospect though, he thinks they were probably too kind to him.

So, what would Adam say to his own children about trying cannabis?

“I won’t tolerate it,” he says. “You can try it once, you can try stuff. Kids do. But I’ll know when things are changing and I’ll come down on you like a tonne of bricks.”

WHERE TO GET HELP: Your GP; Headspace, a youth mental health service provider; in a crisis, other than the Mental Health Emergency line on 13 14 65, you can also call Lifeline on 13 11 14. For information about depression or anxiety, call BeyondBlue on 1300 224 636.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Adelaide’s pioneering bid to end homelessness in the CBD

A new move to learn the names and stories of the homeless is driving a bid to cut Adelaide’s rough sleeper numbers to effectively zero. Roy Eccleston reports.

From YouTube to big screen: Adelaide’s car prankster’s directorial debut

They are the Adelaide brothers who became billion-view YouTube stars after an underwater car stunt gone wrong. Now the RackaRacka duo's debut feature film is about to hit the big screen at a gala event. Read their incredible back-story.