Australian teens trapped by social media apps as the ‘like’ button triggers mental health disorders

As parents of lost teens like Jessica Cleland call for change, social media’s “like” button is being blamed for mental health disorders — and there is an even darker side preying on our kids.

Teens

Don't miss out on the headlines from Teens. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A generation of children is being lost to Meta’s Facebook and Instagram, as well as TikTok with the social media platforms’ “like” button being blamed for fuelling a spike in mental health disorders and soaring rates of suicide and self harm.

Psychologists report teens are basing their self-worth on the number of likes they receive and were obsessively checking their metrics on apps, often left feeling rejected if they did not receive instant approval for their posts.

But there is an even darker side with the apps being used to rate the sexual attractiveness of girls, for cyberbullying and gender based abuse.

And in some instances they are being used to share nude photos of teenage girls without their permission.

Now mental health experts say that addiction and abuse has led to the arrival of a new mental health condition called Problem Internet Use (PIU).

“In its most severe form, PIU could be considered an ‘addictive’ condition (internet addiction), showing features such as dependence, mood alteration, tolerance, withdrawal and harm to psychosocial functioning. People experiencing problematic use at this level may require input from mental health or addiction services,” the Royal Australian College of Psychiatrists said in a position statement on the impact of new technologies on teenagers.

More than four in 10 Australian teens now suffer mental health distress, with experts drawing a link in a rise in cases with the use of social media.

The rate of hospitalisation for intentional self-harm has also surged by 70 per cent in young women aged 15-19 between 2008–09 to 2021–22.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues digital platforms were not toxic in their original formulation but “everything changed beginning in 2009 when Facebook ads the like button and later the share button”.

Instagram followed in 2010 and likes and shares are now key features of other social media platforms.

“You have so much engagement data that you can use algorithms to feed stuff to people based on what will engage them, which means emotions which means especially anger, so everything changed between 2009 and 2012,” Mr Haidt said.

News Corp Australia, along with parents from across Australia, are calling on the federal government to raise the age limit at which children can access social media to 16 as part of a national campaign,Let Them Be Kids, to stop the scourge of social media.

Let Them Be Kids: SIGN THE PETITION

Technology engineer Aza Raskin who helped design the infinite scroll feature of social media apps told the BBC in 2018 social media companies were deliberately addicting users to their products for financial gain.

“It’s as if they’re taking behavioural cocaine and just sprinkling it all over your interface and that’s the thing that keeps you like coming back and back and back”, Mr Raskin, a former employee of technology companies Mozilla and Jawbone, said,

“Behind every screen on your phone, there are generally like literally a thousand engineers that have worked on this thing to try to make it maximally addicting,” he said.

Senior research fellow Dr Ferdi Botha and his colleagues survey more than 17,000 Australians each year for the Household Income and Labor Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) study which quizzes Aussies on household and family relationships, income and employment, as well as health and education.

The survey tracked a 120 per cent increase in rates of psychological distress among 15-24 year olds between 2011 and 2021.

“What you do see is that the rise in mental distress, coincides very closely with the rise in smartphones and iPhones,” Dr Botha said.

Headspace’s head of clinical leadership Nicola Palfrey said the like button was particularly seductive for teenage girls and could directly influence their mood.

“Developmentally, a 13-year-old girl and their need for affirmation is universal,” Ms Palfrey said.

As a result, they are motivated to only post images of a “perfect life’ and those who don’t measure up to the ideal are left with negative feelings.

“One of the things that happens with social media … there really is FOMO fear of missing out,” Australian Psychological Society chief executive Dr Zena Burgess said.

“You spend a lot of time looking at what other people are doing and all the happy snaps which are often quite crafted or curated and have a belief that your life is more impoverished than others, whereas it might none of it may be real.”

At a discussion on Instagram’s algorithms in 2022, Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen revealed the addiction was creating “little dopamine loops”.

An Austin University Texas study in 2020 found teenagers felt more strongly rejected and had more negative thoughts about themselves when they did not receive sufficient social media likes.

The research, which randomly dished out fewer likes to its 613 participants during a social media session, identified youngers already victimised at school as the most vulnerable.

“The findings raise the possibility that technology which makes it easier for adolescents to compare their social status online – even when there is no chance to share explicitly negative comments – could be a risk factor that accelerates the onset of internalising symptoms among vulnerable youth,” the researchers said.

Girls mental health is being much more heavily impacted by social media than boys as they bear the brunt of abuse and denigration on social media.

Headspace’s National Youth Mental Health Survey latest survey from 2020 found “rates of psychological distress continue to be higher among young women than young men, particularly among young women aged 15–17 years and 18–21 years”.

The e-Safety Commissioner reports that “women are twice as likely to have their nude sexual images shared without consent than men”.

The most common channel through which the photos videos were distributed was a Facebook (53 per cent) the commission found.

Up to 50 per cent of teens reported to the e-safety commissioner that they had a negative experience on social media.

One in six teens had received an online threat or abuse, the same number had things said online that damaged their reputation and nearly one in three said that their negative online experience related to bullying that occurred at school.

Women are also significantly more likely to experience gender-based abuse on social media which has enabled the proliferation of global antifeminist, white male supremacist groups that push the subjugation of women.

These groups are credited with influencing teenage and primary school boys to denigrate women.

Experts warn parents who want to manage their child’s access to social media have to take an open approach not a negative one and be humble and curious and ask questions.

“If we’re just negative about it. They’re not going to talk to us about it in the same way that they won’t talk to us about us if we say just don’t have sex, take drugs,” Ms Palfrey said.

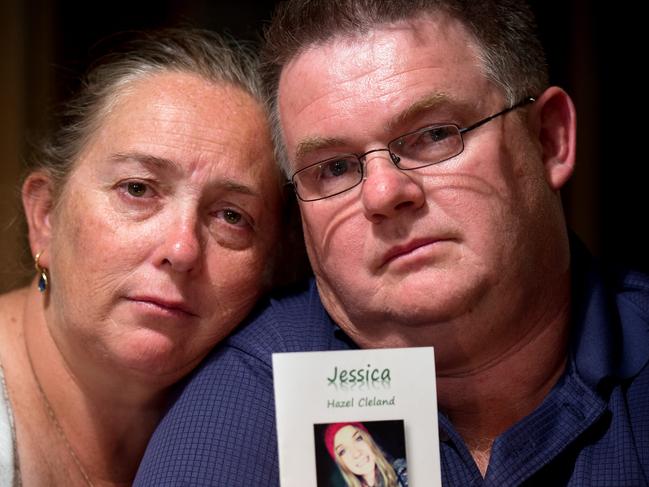

JESSICA CLELAND’S LIFE LOST TO SOCIAL MEDIA BULLIES

Jessica Cleland was 19 years old and had her life ahead of her before she took her own life.

She was excited about starting a new job working with horses during her gap year.

Friends said she was an outgoing woman who didn’t struggle with her mental health.

But her demeanour changed drastically when two former friends started bullying her on social media sites like Facebook and Snapchat.

She was called a “f**king sook” and bombarded with other nasty messages.

The bullying caused Jessica to withdraw from her circle of friends, even refusing to confide in her older sister Amy.

On Easter Saturday, Jessica told her mother Jane Cleland that she was going for a run but later Amy called her parents concerned about an Instagram photo from her sister that read: “I love this place and I am never going to leave”.

Hours later, Jessica’s father Michael Cleland discovered his daughter’s body where the photo was taken.

In a report, Coroner Jacqui Hawkins said social media played a role in Jessica’s death.

“The circumstances of Jessica’s death highlight the important role that social media and other communication technologies can play in young people’s lives,” she said.

“I am satisfied that Facebook and text messaging were problematic for Jessica because easy access to the internet on her phone meant that she was exposed to potentially upsetting communications 24 hours a day … online chat and SMS create an environment where it is easier for individuals to say hateful and hurtful things without facing the immediate consequences.”

Mr Cleland said the age limit to access social media should be raised to 16 as young people “don’t understand the dangers”.

“A decade ago my daughter died by suicide after being bullied online the night before and here we are 10 years on and the same things are still happening,” he said.

“I hope this campaign finally brings about changes in these laws governing bullying, attitudes towards bullying, and education on ways to prevent and stop bullying and help for those affected.”

Mr Cleland said night time bans should also be introduced.

“It would help massively because the young are online to all hours and if they are being bullied this would help give them a rest away from it,” he said.

“There needs to be better education and better management of bullying.”

If this story has raised problems for you please contact:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Suicide Call Back Service: 1300 659 467

Beyond Blue: 1300 224 636

MensLine Australia: 1300 789 978

Kids Helpline: 1800 551 800

13YARN: 13 92 7

More Coverage

Originally published as Australian teens trapped by social media apps as the ‘like’ button triggers mental health disorders