I trekked Mt Everest the ethical way with World Expeditions

The world's highest mountain is becoming notorious for the amount of rubbish left behind, but this adventurous traveller took an Everest trek that treads lightly.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

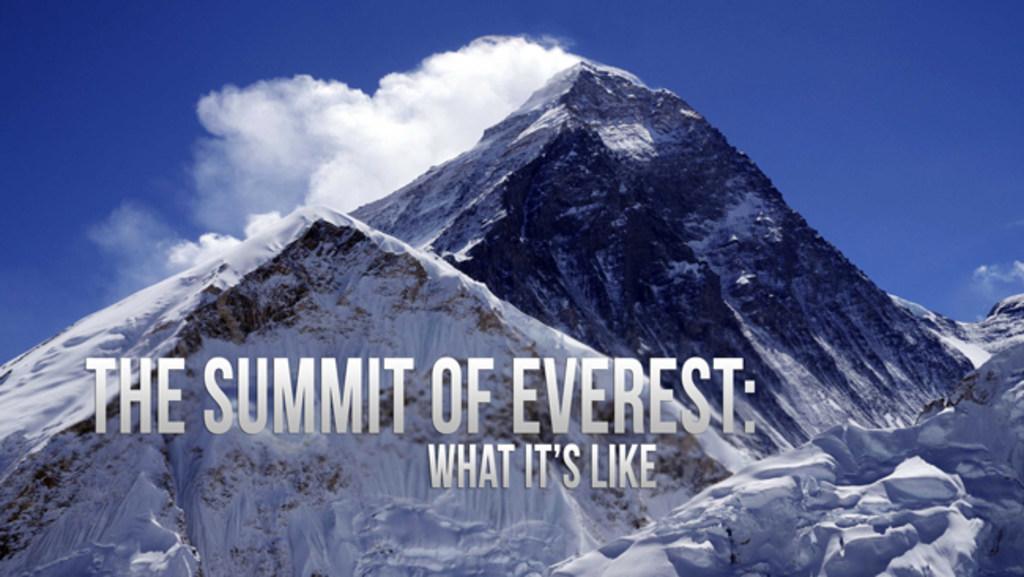

The entire world turned its eyes towards northeast Nepal the day Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the summit of Mount Everest. Seventy years on, adventurous souls still stare starry-eyed from afar, beguiled by the idea of trekking to Everest Base Camp.

An estimated 80,000 visitors trek through the region’s Khumbu Valley each year, with numbers rising, especially now the Chinese and Indian markets are realising their neighbour’s magnificence. And Nepal still hasn’t fully bounced back from its pandemic tourism black hole.

Recurring narratives about trails strewn with rubbish, bullish crowds of serenity-cruelling American accountants, and locals not getting their fair share of tourism dollars have forced a collective rethink of how we should pass through what is, after all, both one of the world’s great biospheres and home of the Sherpa people.

Group-tour operators, including World Expeditions, shy away from the base-camp-at-all-costs attitude nowadays. The company’s Everest Trek in Comfort trip – which doesn’t even reach base camp – claims to be ethical, eco-friendly and have intense local connections. So, does this “short and scenic” trek actually walk that walk?

What’s a comfort trek?

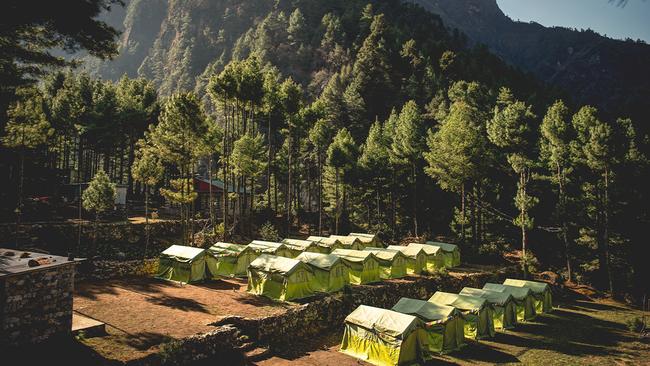

“It’s a five-star camping experience,” according to World Expeditions group leader Bir Singh Gurung, distinct from the three “usual” ways people trek Everest: wilderness camping, teahouse- and homestay-hopping. The guided tour sleeps at a series of permanent tented “eco-camps”, private campsites adjacent to local caretakers’ homes, which the company began setting up around the time of Nepal’s earthquake in 2015. (And “eco-lodges” in larger villages.)

With limited showering opportunities and share composting toilets, this is not glamping, but in the context of light-touch, remote-area tourism, it is an excellent balance of cushy and cultural immersion. Locally made twin-share tents, with sturdy, low single camp-beds, are tall enough to stand up and change in but not really spacious enough to hang out in for too long, especially if you’re sharing with a gear-spreading messy bugger.

Comfort factors manifest in the small details and all-inclusivity: coffee/tea, hot towels and washing water delivered to your tent and decent-ish internet and charging points most nights. And once you leave Kathmandu, everything is basically sorted, including the flight to the “start-line”, Lukla, home of the “world’s most dangerous airport”.

Sherpa home truths

First stop is Ghat village (2530m), in the shadow of Mount Nupla, a couple of hours’ walk from Lukla. An L-shape of green tents awaits in a field outside the double-storey stone-brick lodge of caretaker Gaga Maili (“Middle Sister”) – the mother of a late, respected trekking guide who fought hard to get safe drinking water here.

Lime-green down jacket draped over her striking traditional daywear, Gaga Maili exuberantly drags guests down to the family greenhouse to show off the robust cauliflowers, radishes and spinaches that will feed us. Any surplus is sold in Lukla’s markets.

In the World Expeditions dining room, kept cosy by a dried yak dung-fed stove, it’s pumpkin soup with popcorn croûtons to start. Meals are filling and scrumptious – a carb-filled fusion of local and Western dishes. Paneer, porridge, eggs, buffalo salami, yak cheese, dal, pasta and much rice pass our lips. Red meat is at a premium, however, because Buddhist Sherpas don’t slaughter large animals.

Many homes and guesthouses here cook using firewood – a tradition and economic necessity – but World Expeditions encourages its family-run kitchens to use kerosene or gas. Demand for firewood decimated the Khumbu’s forests, especially before Sagarmāthā National Park was established in 1976.

The path to Everest Base Camp

This up-and-back “introductory” trek follows the Everest Base Camp route, but stops at Pangboche (3930m) before the altitude gets serious, with eight days’ walking. EBC is 1434m higher. Consistently staggering, timeless alpine vistas expand around every bend. Charismatic giants like Mount Kangtega (6782m), with its distinctive saddle-shaped glacier, would be the highest mountain in most countries, yet here it’s simply one of the sublime Himalayan posse.

The shapes and hues of Buddhism interweave with villages and countryside. Mantras painted onto rocks and carved into stone tablets spread the word. Buddha eyes painted on community stupas gaze mystically. Banks of prayer wheels rotate under the power of passing human hands.

Lofty, long wire suspension bridges, trimmed with prayer flags purifying the wind from evil spirits, span chasmic valleys, blue glacial rivers below. Gently pealing bells warn of advancing teams of freight-bearing mules, yaks and dzos (yak-cow cross). Way above, mountain goats bound off cliffs, X Games-style. Way, way above, snow leopards crouch out of sight; glaciers crack, creak and crash.

Benefits of the trek-onomy

The Hillary and Tenzing legacy has helped develop infrastructure in the Khumbu Valley unmatched in similarly remote regions of Nepal. International philanthropy has built hospitals, clinics and the 350-student Schoolhouse in the Clouds, while trekking income brings tangible benefits to villagers. The eco-camp caretaker at Monjo, Dali, built a new family home after the permanent camps arrived. Her tiny old house is now her cowshed.

Trekking footfall helps sustain Sherpa cultural institutions, which symbiotically enriches visitors’ visits. Above Namche Bazaar – the fast-developing unofficial regional capital, our first chance to see Everest – we stay at eco-lodge Hotel Sherwi Khangba, which offers two vivid snapshots of Himalayan life. Its Sherpa Culture Museum covers the traditional day-to-day, while the photos and memorabilia of the Everest Documentation Center unfurl stories of the real mountain heroes: Sherpa guides, one of whom has summitted Everest 29 times.

Ten kilometres further up, trekkers and climbers stop at Tengboche Monastery for blessings. Their entrance fee helps 50 monks keep this bastion of ancient Buddhism in divine condition.

The realities

Inevitably, in places the developing-world infrastructure isn’t coping with the crowds. The forest next to rock stairs leading up to 135m-high Hillary Bridge – soon to have a bungee jump – is thick with trash and used loo roll.

Meeting first-world eco and ethical goals in an isolated region of a country that is 145th on the GDP/per capita list is a fraught challenge, yet World Expeditions tackles issues pragmatically. On this 100 per cent carbon-offset trek, special bags are provided to collect rubbish (voluntary) and our drinking water is boiled because Nepal’s recycling facilities can’t yet cope with the volume of plastic waste as it is.

Commonly, independent porters, wearing inadequate shoes, still carry one-and-half times their body weight in soft drink and village store stock. World Expeditions porters, however, are limited to carrying 35kg, are supplied with boots and warm clothes, and paid at the Trekking Agencies’ Association of Nepal rate. Properly acknowledging, treating and paying the team that “gets” you through a high-altitude trek is the most fundamental measure of how trekking in the Everest region is changing for the better.

Finally, at Pangboche a steamy glass of green tea lands at my frost-licked tent’s doorstep. The all-knowing 8000m-plus trinity – Everest, Lhotse and Nuptse – seem to exhale clouds. Dawn turns their snows peach. No words need be spoken. Retracing our steps back down the Khumbu Valley, small things now loom larger. The copper-orange bark of a Himalayan birch. Rhododendrons in bloom. The energy and grace of village life. Everest is so much more than its magnificent peaks.

The writer was a guest of World Expeditions.

Trekking Everest

World Expeditions’ 12-day Everest Trek in Comfort costs $3770, including transfers, meals and use of sleeping bag/liner, and warm down jacket.

How to fly to Kathmandu from Australia

Malaysia Airlines flies from east coast Australian capitals (via Kuala Lumpur) to Kathmandu daily.

How Everest trekkers are making a difference

There’s no denying it, discarded plastic bottles are still a blight on the Everest Base Camp trek. In 2019, NGO Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) began its Carry Me Back program. Downward trekkers clip on 1kg pre-packed bags of shredded waste to deliver to Lukla, where it is transported to Kathmandu and recycled. In the 2023 spring season, 18,000 bottles were recycled.

More Coverage

Originally published as I trekked Mt Everest the ethical way with World Expeditions