‘I knew what Sam wanted’: State Minister Nat Cook opens up about death of her son and organ donation

State Minister Nat Cook knows she will never get over losing her teenage son Sam. But she says there’s some comfort knowing lives were saved through his decision to be an organ donor.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

State Minister Nat Cook knows she will never get over losing her beloved teenage son in the most abhorrent of ways – a one-punch attack.

But there are moments which are especially hard and emotionally triggering.

The death late last year of full-of-life Charlie Stevens, 18, was one of those.

Charlie, the sports-loving son of SA Police Commissioner Grant Stevens and wife Emma, died after being struck by a car at Schoolies Week.

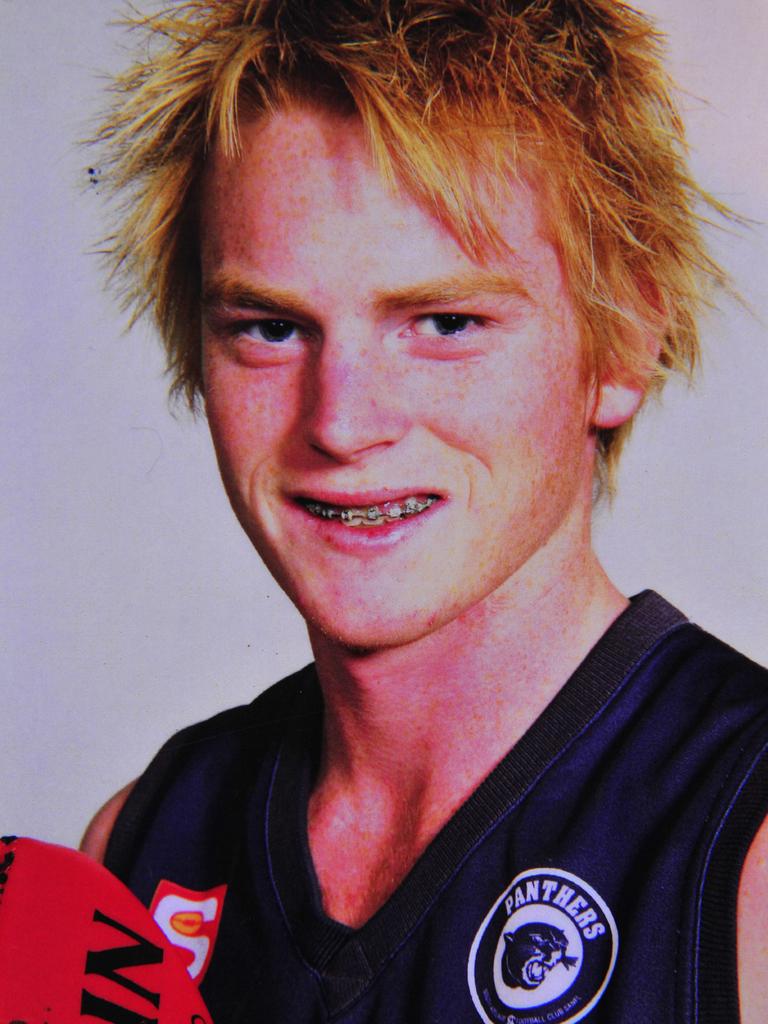

She and husband Neil Davis lost their eldest child Sam, a budding young footballer, at 17 after he was struck in an unprovoked attack at a party.

On the eve of DonateLife Week, Ms Cook opens up about that terrible night 16 years ago and how she has learned to live with the “loss (which) becomes part of your life”.

“Charlie’s death was particularly hard … I went to Charlie’s funeral, I know Grant and Emma and found sitting behind all of Charlie’s friends really triggering,” she says.

“I struggled and found it really, really difficult … my Cabinet colleagues that were there knew and helped me through it.

“You don’t want to make those things in any way about your own experience but I have always struggled when there is a similar story (to Sam’s).

“There is always a terrible story behind the loss of any young life but when it is senseless and when it is someone of a similar age, a similar type … they were all footy boys, tradies – that was Sam’s world and it was Charlie’s. They were both just good kids.”

Sam had kicked five goals for South Adelaide’s under-19 side, in a clash against North Adelaide in the SANFL, on the day he died.

He, nor his family, would ever get the chance to know just how good he could have been but secretly hope a little boy who received one of their son’s organs in a life-changing operation might still be running around a footy field somewhere.

“The house is full of Sam, we are always thinking of him … the loss becomes part of your life,” SA’s Minister for Human Services and Seniors and Ageing Well says.

“Early in the piece it is really, really raw and painful … you think you will never laugh again – you want to cancel Christmas.

“It is all the things; feeling really quite desperate around milestones and birthdays … you look at family and friends and think, ‘How can you be happy, how can you be celebrating?’.”

Despite the enduring heartache, she says she has learned not to live in the “what if”.

“You can punish yourself by wondering ‘what if and where would he be?’,” she says.

“You do look around and go, ‘Would he have kids? What would he have done? What life would he have led?

“I look at Charlie Dixon and the size of him – he is a similar age to what Sam would be now – and go, ‘Would he have been that?

“But I think if you keep doing that, really you just punish yourself.

“So, at some point you have to go ‘Stop’ … I find myself internally saying, ‘Just cut it out and get on with it’.”

Ms Cook says Sam’s prognosis was dire from the start but she and Mr Davis still hoped they’d have longer to say goodbye.

“For us it was very clear from the time Sam was in the emergency room that there was likely no coming back … (the doctors) painted a very grim picture and we knew he had a devastating injury – the injury to Sam was almost identical to (cricketer) Phil Hughes’ (who died aged 25 after being struck on the side of his head with a cricket ball),” she says.

“We were working towards a timeline we could spend with Sam … hundreds of people came to see him, his family and friends were lined up outside in the corridors.

“But his body started to give up … we didn’t get a night to just sit with him – it all happened pretty quickly in the end.”

Still, she says, like the Stevens, her family finds some comfort in knowing several lives were saved through Sam’s decision to be an organ donor.

“Before Sam died I was working as a registered nurse in intensive care and flight retrievals … he knew about organ donation because we’d spoken openly about it and how I looked after people who had donated or received organs,” she says.

“So, when he went and got his driver’s licence, at the very first opportunity, he selected to be an organ donor on his licence.

“I knew what Sam wanted and was very at peace with the decision … it was just one decent part of a really, really shit situation.”

The family would later learn of the lives Sam’s selfless act would save.

“There were grandparents who got to see their grandchildren, a mum of a large, young family who got to live and be able to parent and love her children … we also knew there was quite a young kid whose heart would be better due to having Sam’s (heart) valves and hoped one day he would be this great footballer who loved chicken parmies,” Ms Cook says.

After losing her son, the now politician stepped away from nursing to focus instead on setting up the Sammy D Foundation, a charity aimed at educating young people on the impacts of bullying, violence drug and alcohol misuse

“(Sam’s death) changed my ability to be able to work in the hospital and intensive care, I tried to go back to do retrievals but couldn’t … I just felt I couldn’t cope.

“But I promised Sam I would do something to (give some reason) to his death … his legacy through the Foundation is enormous – and there is the organ donation.”

Four years after Sam died, Ms Cook and Mr Davis welcomed a miracle bub.

The couple had tried for many years before Sam’s death for a second child – undergoing about 13 rounds of IVF before finally giving up.

They say Sid, now 11, is uncannily like the big brother he never got to meet.