This generation’s teenagers are the most depressed in history, and they’re only getting worse

DESPITE being healthier, better educated and more connected to a world of opportunity, this generation’s teenagers are the most depressed in history. And the reason why is in their pockets.

DESPITE being healthier, better educated and more connected to a world of opportunity, this generation’s teenagers are the most depressed in history — and the reason why is in their pockets.

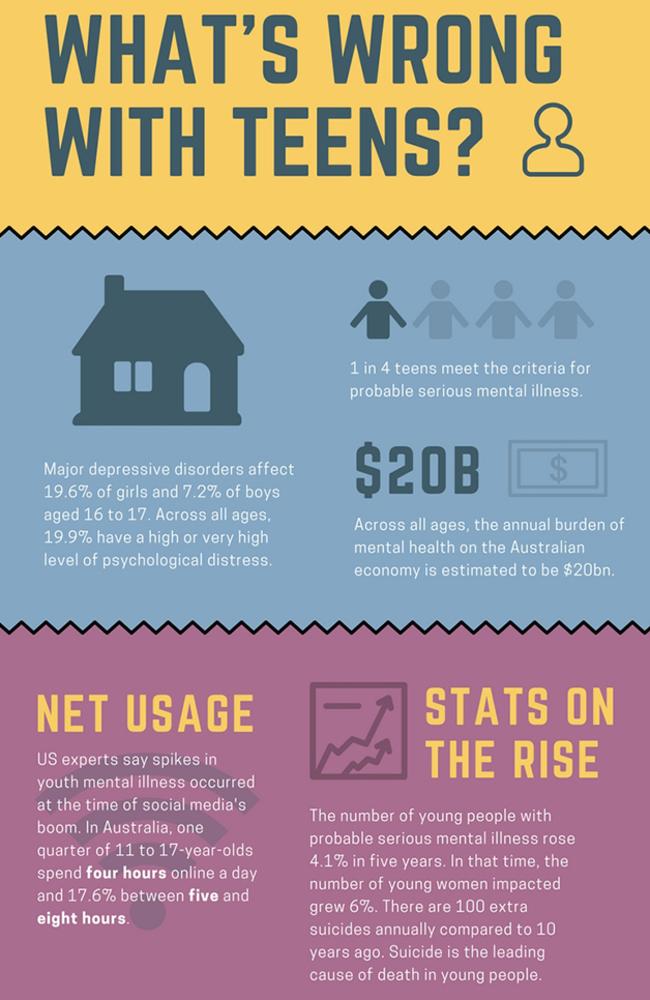

Startling research indicates that rates of mental illness in young people are at their highest, with one in four Australian adolescents showing signs of a probable serious psychological issue.

More are taking their own lives, with an extra 100 annual suicides now compared to 10 years ago.

Experts say a potent cocktail of unique modern stressors, dwindling socialisation and non-stop exposure to the planet’s many problems is to blame.

Daniel Hermens, a psychologist and researcher at Sydney University’s Brain and Mind Centre, said the 15 to 25 age group has the most significant mental illness burden — and it’s getting worse.

“Young people now have better awareness and are intervening earlier to seek treatment, but that’s not the entire reason for the increase,” Dr Hermens said.

“It’s the pressures we see in society — cost of living, world affairs … a fall in socialisation that’s ironically driven by social media. It’s new or different types of stress. And substance abuse remains an issue.”

The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry (ANZJP) warned in 2014 that data from a range of sources showed that the burden was increasing.

Since then, researchers have recorded steady increases in rates of illness across all youth subgroups.

Mission Australia’s latest yearly analysis found 22.8 per cent of those aged 15 to 19 exhibited signs of a serious illness, up from 18.7 per cent in 2011.

“We’re talking about an alarming number of young people facing serious mental illness, often in silence,” Mission Australia boss Catherine Yeomans said.

Even with growing awareness and a range of youth-targeted initiatives, data from Beyond Blue concluded that suicide is the biggest killer of young Aussies, more than car accidents.

In 2015, 391 people aged 15 to 24 died by suicide compared to 290 a decade earlier.

Teens across the board are struggling and young men are more likely to suicide, but girls are twice as likely to be in “severe psychological distress”, Mission Australia found.

The number of young women showing signs of severe mental illness hit 28.6 per cent in 2016, up more than six per cent in five years.

American clinician Catherine Steiner-Adair said one reason was the worsening impact of body image.

“Girls are continually bombarded by media messages, dominant culture, humour and even political figures about how they look — no matter how smart, gifted or passionate they are,” she told NPR.

Analysis of 170,000 American youngsters by John Hopkins University found girls were more likely to use new means of communication and were exposed in greater numbers to its negative effects.

Here at home, the ANZJP analysed eight independent studies on youth mental health and found five of those demonstrated an increase in symptoms in adolescent girls.

Sophie Hope was 12 when her illness symptoms began, following a sexual assault that led to post-traumatic stress disorder.

She’s now 24 and working in the youth mental health space, and said she regrets taking so long to enter treatment, blaming the stigma attached to mental illness for going it alone.

“It took me a long time to seek help and so things just got worse before that. I was 17 when I was diagnosed with PTSD, obsessive-compulsive disorder and associated depression and anxiety.”

It’s a serious combination of issues that in the past has seen her hospitalised and unable to function.

“I think if I’d been able to get help earlier, I would’ve been able to manage it. The care part of my journey is still quite recent, the past five years, and it’s definitely helped. I’m on a good path.”

As well as her experience, the Headspace National Youth Reference Group adviser has insight into what teens are going through now.

“I think a big contributor is that the world is so much smaller now,” Hope said.

“We’re bombarded with all the world’s problems in intense detail. It’s important to hear those stories so we can have empathy and help change things, but it’s non-stop. There’s no off switch.”

Bad news has always been there but in the past was perhaps confined to the pages of a newspaper or a 30-minute evening news bulletin.

“Now it’s in our pockets on our phones, it’s always there and you see it all the time, even if you’re not looking for it.”

Those devices and the constant connection they promote have a lot to answer for, experts say.

MORE AND LESS CONNECTED

Large-scale studies in the US have found that a significant uptick in mental illness rates, after several years of stability, occurred at the same time as the social media boom.

People reaching adolescence now are the ‘screen generation’, having grown up with smartphones, tablets, unfettered internet access and social media.

“While they’re very social online, I think young people are having less actual contact with people in many ways,” Dr Hermens said.

“Socialisation is a really key issue in youth mental health so people who are starting to become isolated in any way are going to be at risk.”

A lack of engagement with the world could see emerging issues or simply a predisposition to illness spiral into a disorder, he said.

“When it comes to the physical development of young people, socialisation is very important.”

The low physicality of the connected world is taking its toll.

Low levels of activity combined with high screen time have been linked to poor mental health by a University of Queensland researcher.

While Dr Asad Khan’s study focused on youth in developing nations, he said the findings had implications for developing countries too.

“Technology is now a common part of teen lives so it’s important to balance screen time with an active lifestyle, in order to minimise the risk of depressive symptoms and to optimise wellbeing.”

Issues like cyber bullying have been well-documented but social media has also been linked to increases in body dysmorphia, anxiety and depression.

RELATED: Facebook conducted research to target emotionally vulnerable and insecure youth

The frightening prospect for parents is supervising technology usage, Dr Steiner-Adair.

A child can be in the same room as mum and dad but battling some emotional crisis that carries on constantly in the palm of their hand.

Whether on Instagram, Facebook or Snapchat, young people place a lot of importance on putting their best filtered foot forward.

Far from being just an exercise in vanity, teenagers see social media as part of their identity, Dr Hermens explained, and compare themselves to peers via it.

“But they’re seeing a false version of their peers. What people post on Facebook and the like is generally positive, a sort of curated illustration of their life,” he said.

“Young people compare themselves to others but the comparison isn’t true. We only tend to see the great things people are experiencing, a wonderful holidays or a great date, all the positive things.

“A vulnerable person might see that and think that the rest of the world is doing better than them. They come to a conclusion that their life isn’t as good and that (feeling) can exacerbate a predisposition or proneness to a depressive disorder.”

Young women in particularly are more likely to compare themselves to others — often unfavourably, Dr Steiner-Adair said.

Many of her young patients say they view their “entire identity” through a prism of likes, tags, shares and replies.

A GLOBAL EPIDEMIC

Trends in Australia mirror those in other western countries, with anxiety and depression rates in American high school students soaring since 2012.

“It’s a phenomenon that cuts across all demographics — suburban, urban and rural; those who are college bound and those who aren’t,” Time magazine wrote on the issue last year.

Cornell University’s Jane Whitlock explained to the magazine that teens exist in an era of economic instability, global insecurity and technological advancement.

“If you wanted to create an environment to churn out really angsty people, we’ve done it,” Dr Whitlock said.

“They’re in a cauldron of stimulus they can’t get away from, don’t want to get away from or don’t know how to get away from.”

Researchers have collected psychological data since 1938 and found five times as many high school and university students are battling depression and anxiety than their counterparts during the Great Depression era.

RELATED: Youth homelessness is Australia’s preventable $600 million problem

In the United Kingdom, it’s a more alarming story. Rates of depression among young people have soared by a whopping 60 per cent in the past 25 years.

As a special report in The Independent concluded, Britain is facing “an epidemic of young people at odds with the world around them”.

It’s not just developed nations impacted, with a recent World Health Organisation report declaring that depression is now the leading cause of illness and disability in youth globally, rising 18 per cent since 2005.

FIXING THE PROBLEM

For several years, Australian schools have taken a proactive approach to mental wellbeing, and good thing too.

A 2014 survey revealed the major role teachers play in spotting issues and encouraging intervention.

It found that in 40 per cent of cases, a school staff member was the first to suggest a struggling young person seek help.

Teachers and other school staff provided 51 per cent of those students with a mental disorder with informal support, the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents report from the University of Western Australia said.

Early intervention is the best course of action and teachers are well placed to identify any issues quickly.

However a Beyond Blue survey of 600 educators found half worry they don’t have the time to focus on mental health in students.

Parents also need more guidance with the process of encouraging an open dialogue at home.

And while it’s a big contributor to the problem, Dr Hermens said the internet is also part of the solution.

Support services are investing in their digital offerings, in a bid to reach at risk youngsters where they spend most of their time.

“What you’ll see in the next five years is a big move towards online intervention,” Dr Hermens said.

If you or someone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or lifeline.org.au