The sad hoarder disorder that becomes so obsessive the clutter can be a killer

WE all like to keep the odd treasure, but when keeping everything becomes an obsession it may be hoarding disorder. So why do people do it?

Mind

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mind. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Adelaide house no one should have to live next door to

- ‘Rats, filth but we can’t get this eyesore cleaned up’

- Increase in hoarders and people living in squalor prompts launch of website

- RSPCA prosecutes cat owner over shockingly squalid conditions in house

THERE is a touch of magic about hoarding, where people just cannot control their clutter.

It is a belief that objects as trivial as a ticket stub have an essence beyond its physical characteristics, to the point the owner cannot bear to throw it out.

While many people keep the odd treasure for the sake of memories, hoarders become buried in treasure to the point of squalor with the risk of vermin, disease and fire.

This is when clutter can be a killer.

In South Australia the problem has grown so much SA Health has devised a “Foot in the Door” policy to deal with extreme domestic squalor where severe hoarding and just plain mess creates a situation where cooking and cleaning are not possible, putting children and neighbours at risk.

The policy under the most recent Public Health Plan comes amid rising cases where authorities need to gain access to properties where squalor is a problem, but which may involve people with mental health issues.

Professor Mike Kyrios, Director of The Australian National University Research School of Psychology, said people with hoarding disorder are falling between the gaps of Australia’s medical system.

He estimated hoarding disorder affects up to 6 per cent of the population — or up to 1.3 million people.

“This is a severe mental health condition that affects people’s lives and is associated with unnecessary deaths. We know that 25 per cent of deaths from fires in homes occur in the homes of people with a hoarding problem,” Prof Kyrios said.

Professor Randy Frost, an American expert in hoarding disorder who will give seminars in Adelaide on the subject next month — as well as Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane — says we all love certain possessions which trigger pleasant memories.

In hoarders, this attachment becomes exaggerated to a point they find it hard to part with anything.

“For all of us, possessions have a magical quality, an essence that goes beyond the physical characteristics of an object,” Prof Frost said.

“For example, saving a ticket stub from a favourite concert. There is nothing about the physical

characteristics of the ticket stub that differs from any other ticket stub.

“The association with the event is in our head, not in the physical object. However, we see

it as part of that object.”

Prof Frost says hoarding is a set of behaviours including difficulty discarding or letting go of

possessions, regardless of their value.

Hoarding becomes a problem when the clutter that results begin to interfere with the person’s ability to function.

Rooms including kitchens and dining rooms become so full of possessions people can’t cook or sit at a table. Hallways become hard to negotiate, bedrooms are full, and as for front and backyards ...

Apart from vermin and fire dangers, it makes it hard for families to function, annoys the neighbours and makes access difficult for emergency personnel.

Just why people hoard is a complex issue with relatively little known about the causes, according to Prof Frost.

“We do know that it is partly genetic, that information processing deficits contribute to it, and that attachments to possessions and beliefs about possessions also contribute,” he said.

“It is not clear that there are triggers. The behaviour starts early in life and gets

progressively worse in most cases.”

Hoarding also has been linked to insecurity, where people acquire objects as a defensive wall against perceived threats.

Don’t confuse hoarding with collecting, or just being lazy.

Collectors tend to collect a single category or small number of categories of

items, while people with hoarding disorder collect unlimited numbers of categories.

“Collectors also tend to organise their items and are proud to display them,

neither of which characterises people who hoard,” Prof Frost said.

“People who hoard are definitely not lazy. Many of them spend hours trying to get

control over their possessions. They are simply unable to.

“A key characteristic that differentiates someone with a hoarding problem from someone whose home fills up for other reasons is the extent to which they are attached to their possessions and

the distress they would experience trying to get rid of them.”

That distress can create danger — vermin, insects, mould, broken sharps, cooking problems, falls, general filth and particularly fire are among risks.

In 2013 hoarding disorder was made an official diagnostic category in the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric

Association.

SANE Australia says mental health experts are only just beginning to understand the complexities of hoarding.

In Australia, until recently it was recognised as an anxiety disorder, but is now considered a stand alone disorder.

Treatment is a challenge.

“We have developed a cognitive behavioural treatment for hoarding that has shown

some promise,” Prof Frost said.

“It involves focusing on the three aspects of hoarding — excessive acquisition, difficulty discarding, and disorganisation.

“Based on the limited research on the topic, gains made in therapy seem to last. However, this has only been studied up to a year after the end of treatment.”

■ If hoarding is an issue for you or someone you know, call 1800 187 263 or go to sane.org

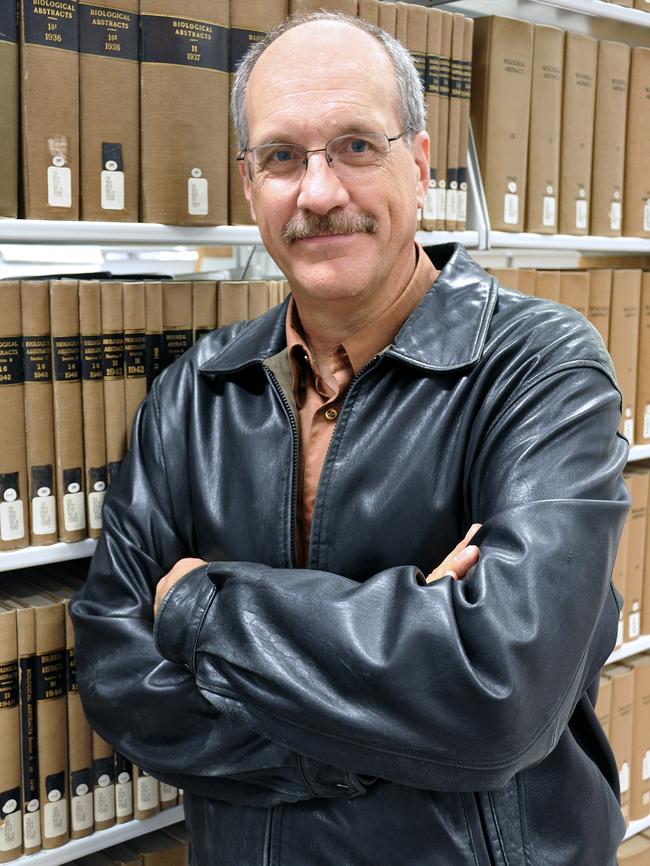

The expert

Randy O. Frost is the Harold and Elsa Siipola Israel Professor of Psychology at Smith College in

Northampton, Massachusetts.

He has written more than 170 scientific papers, articles and books on hoarding disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder including Buried In Treasures and Stuff.

He is a keynote speaker at the World Congress of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies in Melbourne next month where he will discuss latest treatments for hoarding disorder.

In Adelaide he will hold a free seminar for the general public and a $99 per ticket session for people who deal with hoarders in their jobs. Both be held on June 17 at the Grand Chancellor on Hindley. Phone: 0448 606 005.