Push for ‘right to try’ laws to allow the terminally ill to test experimental drugs

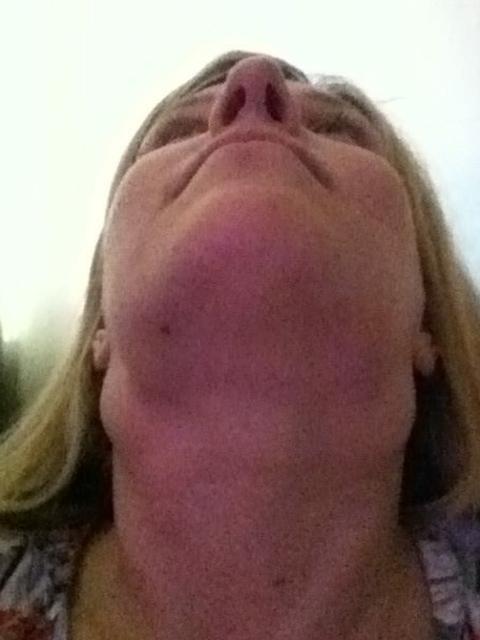

IN 2015, leukaemia was set to take Deborah Sims’ life. With some research she found new drugs that could save her — but they weren’t available in Australia. Now cancer-free, she’s standing up for sufferers’ rights to try new drugs that may save their lives.

Illness

Don't miss out on the headlines from Illness. Followed categories will be added to My News.

‘THIS week marks the end of a turbulent time of my life. For the past three years I’ve been travelling to the other side of the world for lifesaving treatment at a huge personal cost. This week, I will walk into the Peter MaCallum Hospital in Melbourne to collect my lifesaving drugs from the pharmacy.

In 2015 I was set to die. I had an incurable form of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia from which I’d relapsed after chemotherapy failed. But for a 40-year-old mother with three young children, death was not an option.

Following online research I discovered there were novel drugs in development that might just save my life.

The problem was I couldn’t access them in Australia. Only 3 per cent of terminally ill patients can get onto trials of such drugs.

After a trip to the US, and a lucky meeting with a British doctor, I moved to London to join a clinical trial of an experimental drug at Bart’s Hospital.

Ironically my wonder drug, venetoclax, was invented in Australia but I had to travel to London to take it.

I was lucky enough to become patient 49 on a ‘phase 1’ trial. This combination therapy followed a first in human safety trial of 80 brave patients, but came before the drug was listed by the Food and Drug Administration in the US.

I was one of just 75 people worldwide who received the treatment. Within three months I was in complete remission and within seven months I had no detectable cancer — it just melted away.

I had to fly to London for monthly appointments for a year, then three monthly appointments up until now. I have had no traceable disease for 29 months and take my drug daily with no side effects.

I work full-time and my children have their mother. But I am one of the very few lucky ones. Red tape is preventing dying patients from accessing lifesaving drugs.

I am now campaigning for all terminally ill patients to have access to the latest drugs.

Right to Try, letting patients legally access these, is an important part of that. As it stands, dying patients have to wait for phase 1, 2 and 3 clinical trials to be completed before drugs are made available.

My CLL drug has taken 30 years to reach that stage.

It has since received Therapeutic Goods Administration approval for use in Australia — but is still not available on pharmacy shelves.

Right to Try laws in the US were created to enable terminally ill patients — with advice from their treating doctors — to try experimental therapies which have completed phase 1 testing but have not yet been approved for use by the FDA.

The legislation has its roots in the HIV epidemic. The Dallas Buyers Club movie shows how people with HIV sought access to experimental drugs through illicit means.

Legislation in the US began in 2014, thanks to the work of the Goldwater Institute, a libertarian think tank objecting to government interference between patients, doctors and pharmaceutical companies.

“This is really a law for people who are very sick, who have exhausted all treatment options and who cannot enrol in a clinical trial,” Goldwater’s Starlee Coleman explains.

If a doctor believes an investigational drug is your best hope, they can initiate contact with that drug manufacturer’s compassionate use program to discuss options for access.

“It’s only for people who say, ‘I understand the risk. I know this drug is not fully approved,” Coleman says.

The TGA’s Special Access Scheme allows doctors to prescribe a drug listed anywhere in the world to dying patients.

Australia should extend this to the US model of allowing access to all drugs which have passed phase 1 testing.

Doctors knew my drug was working years ago. Signing the consent form to take part in the clinical trial was terrifying but it was more terrifying knowing the alternative. All patients, with informed consent, should have the opportunity to save their own lives.

Deborah Sims is an executive with the Institute of Public Affairs.

Terminally ill fight for ‘right to try’ new drugs

A DOCTOR has launched an impassioned plea to support “right-to-try” legislation allowing terminally ill people to access experimental drugs.

Such legislation has been approved in many states in the US and President Donald Trump has signed federal legislation giving terminally ill patients the right to try drugs that are still undergoing clinical trials.

Those laws do not force drug companies to supply such drugs, or offer subsidies, but they do allow a pathway for dying people with no alternative treatment apart from palliative care to try drugs which have shown promise and are approved for human use in clinical trials.

The Leukaemia Foundation supports the move, releasing a statement saying: “We recognise for some people, proven therapy pathways do not work and after all options have been exhausted, an individual should have the right to choose, and for some this means a different treatment pathway from sources outside of Australia.”

Associate Professor Michael Keane, a specialist anaesthetist with research positions at Swinburne University and Monash University, has written in favour of the move in the Medical Journal of Australia.

“Right-to-try legislation, which provides a pathway for access to experimental treatments for patients with terminal diseases or conditions, should be thoroughly supported here in Australia, as it represents not only compassion but an enlightened understanding of the complexity of drug regulation,” he wrote.

“Those who steadfastly defend the status quo of Australian drug regulation are defending a system so lacking in a sophisticated understanding of complex processes that it has been justly derided as the ‘magic moment’ system.

“The magic moment is the point of approval of the drug: The moment between pre-and post-licensing, when it goes from being used only in a tightly controlled, narrowly defined trial population to being used more widely in less well controlled settings by heterogeneous patient populations with confounding factors.

“Currently, it is very difficult for anyone to access an unapproved drug outside of a clinical trial (and they might not even get the drug in the clinical trial if they are randomly allocated to the placebo arm) no matter how much evidence has accumulated regarding safety and efficacy.

“Then comes the magic moment, many years and many lives down the road, when the drug is approved for certain indications.

“For patients with uncommon yet lethal diseases, there exists a large unmet need for new therapies.”

Prof Keane acknowledged there was strong opposition to the legislation among many doctors, and stressed all drugs and situations were different.

“An expensive drug for which pre-phase 3 testing shows a 1 per cent improvement in one subscale of dementia is a completely separate beast to a drug that melts away “incurable” tumours in young people,” he writes.

“Right-to-try legislation doesn’t give a patient a right to access therapies in earlier stages of development, but it prevents regulators from prohibiting access if a company, a dying patient and treating doctor want to try a therapy that has shown significant promise.”

— Brad Crouch

Risk v reward

IN Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) regulates therapeutic goods, which can carry risks as well as benefits because to be effective they must modify the way the bodywork.

THERAPEUTIC goods must be entered in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) before they can be lawfully supplied in or exported from Australia, unless exempt from being entered in the ARTG, or otherwise authorised by the TGA.

THE TGA enters therapeutic goods in the ARTG when:

■ Higher risk therapeutic goods have been assessed as meeting the requirements for quality, safety and — where appropriate — efficacy and/or performance; or

■ Lower risk medicine, biological or medical device applications have been validated.

A SPONSOR (i.e. the individual or company intending to supply the goods) is responsible for meeting the regulatory requirements of the therapeutic goods legislation.

THE TGA’s Special Access Scheme allows doctors to prescribe to dying patients a drug that has been listed anywhere in the world.

Originally published as Push for ‘right to try’ laws to allow the terminally ill to test experimental drugs