Godfather, Jodie Foster and Jack Nicholson: 25 times the Oscar winners were indisputably correct

For all the controversy Oscar winners attract, sometimes the chosen films and actors just can’t be questioned. Here are the indisputable winners.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When they announced The Departed as the winner of the 2007 Academy Award for Best Picture and followed up the next year with No Country for Old Men, it made us feel that the world’s most famous awards were worth watching after all.

The same could be said for Vivien Leigh’s turn as Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire in 1952 and Marlon Brando’s prize for Best Actor in On The Waterfront a few years later.

Of course, they were before most of us were born and the wider field of actors in modern cinema was always going to make for greater competition and controversy.

But the bottom line is that, for all the debate that rages every year, the Academy Awards can also get it right.

The list of Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Movie winners contains names that couldn’t really be questioned by anyone other than a contrarian in the mood for an argument.

Philip Seymour Hoffman just had to win in 2006 for his transformative work as Truman Capote, just as Jack Nicholson had to win for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1976 and Rod Steiger’s 1968 win for In the Heat of the Night rewarded one of the greatest performances ever committed to film.

Anthony Hopkins (who won in 1992 for Silence of the Lambs) fits that bill, even though he beat out Nick Nolte at the top of his game in Prince of Tides, largely because his performance redefined how we view horror and menace in cinema.

The unquestionable Best Actor list of winners is shorter than the controversial one but it’s well worth revisiting for any serious cinephile.

Perhaps the first truly great Best Actor winner was James Cagney for acting, singing and dancing against type in the 1942 masterpiece Yankee Doodle Dandy.

Dismissed too often as a one-dimensional tough guy in the early gangster movies, this is the actor the legendary Citizen Kane director Orson Welles once described as the “the greatest actor who ever appeared in front of a camera”.

His winning turn as songwriter and performer George M. Cohan, from his quiet thoughtfulness to gravity-defying dance routines that set the bar for every musical since and inspired everyone from Gene Kelly to Michael Jackson, stands up remarkably well when viewed 81 years later.

We then had to wait until 1954 for Brando to tell the world he “could have been someone” and announce his arrival as an acting giant in On the Waterfront, while Gregory Peck’s constantly restrained performance as Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird was sublime. He beat a stellar field in 1963 including Peter O’Toole (Lawrence of Arabia), Burt Lancaster (Birdman of Alcatraz) and Jack Lemmon (Days of Wine and Roses), all of whom should have won in a normal year, but the win was indisputable.

Peck’s thoughtful southern defence lawyer showed generations to come that bravery and strength could come without raising a hand to anyone.

In 1968, Steiger won for a performance that should be required viewing for every safe and predictable filmmaker going around today.

Steiger’s police chief Bill Gillespie in In the Heat of the Night is a man indoctrinated into racist ways by his geography and history but smart enough to see beyond the prejudice and find a way to work with Sidney Poitier’s more sophisticated Philadelphia detective.

While both were outstanding developing a reluctant working relationship, Steiger’s layered performance was one for the ages.

The list of non-negotiable Best Actress awards is either more or less obvious, depending on the argument that there were fewer great female leads until well past the first half of the 20th century.

Vivien Leigh became a legend in Gone With the Wind but she reached an artistic high with her performance as a troubled ageing southern belle in A Streetcar Named Desire.

At the other end of the spectrum but in a role that has become part of our ethos, Julie Andrews’ work in Mary Poppins produced a certain winner when she beat out Anne Bancroft, Sophia Loren, Debbie Reynolds and Kim Stanley in 1965. It wasn’t the best work of any of her rivals and Andrews captivated the world as the charming, magical nanny in Edwardian London.

Elizabeth Taylor showed the world she was so much more than a glamour actress by owning every scene in the intense Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Like Andrews, she beat a solid 1967 field including Vanessa Redgrave and Lynn Redgrave but her turn at the age of just 33 as one half of a troubled ageing couple (with real-life husband Richard Burton) is among cinema’s most compelling work.

Meryl Streep is cinema’s most awarded actress, with 21 Oscar nominations and three wins for Best Actress, but nothing matches her work in Sophie’s Choice.

Her role as the Polish mother who carries endless guilt after being given an impossible and insidious choice by a Nazi officer for the life of one of her children at the expense of the other is a masterwork. Nobody in 1983 – and very likely nobody since – could have argued their case for beating her.

Multiple winners Frances McDormand and Hilary Swank are rated among the best modern-day actresses, and few could dispute their respective Oscars but McDormand’s first work in Fargo was a lock for the 1997 ceremony. Her opposition of Brenda Blethyn, Diane Keaton, Kristin Scott Thomas and Emily Watson turned in solid work that was far from the best performances, while McDormand breathed life into an intriguing fictitious character that anchored the Coen brothers’ breakthrough Hollywood success after several minor hits and misses.

While it would seem obvious to suggest the immortal Bette Davis must have been an indisputable winner once in her storied career, it isn’t the case. The actress who paved the way for modern roles for women 50 years before strong, aggressive female leads became more commonplace won for Dangerous (in 1936) and Jezebel (in 1939). They weren’t her best performances. She didn’t win for 1934 film Of Human Bondage, All About Eve (1950) and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) – films which displayed her legendary depth and range.

It’s very difficult to gauge the merits of the Best Director prize,with Best Picture winners In the Heat of the Night, Gladiator, Spotlight and Moonlight among those not to transfer success to the director.

Most notably in film history, Bob Fosse won Best Director for Cabaret in 1973 at the expense of Francis Ford Coppola, who helmed The Godfather. A young Steven Spielberg wasn’t acknowledged for overcoming massive production problems and delivering the recognised masterpiece Jaws at the 1976 awards.

Many would assume Gone with the Wind was the first great Best Picture winner (in 1940) but there are just as many critics who would argue it beat a better film in The Wizard of Oz.

We had to wait until 1944 for the first truly indisputable Best Picture winner to show up in the form of Casablanca.

It was a solid year with 10 Best Picture nominations, but nobody could dispute its win over the likes of Heaven Can Wait, For Whom the Bell Tolls and Song of Bernadette.

While many pre-1950s films are lost on the current and even recent generations, Casablanca remains a favourite with film lovers of all ages.

From the Humphrey Bogart-Ingrid Bergman chemistry to the exotic Morocco location, the reminder of a Nazi threat and a now nostalgic soundtrack, Casablanca has been captivating cinephiles for the greater part of a century. More than that, it’s a brilliantly scripted and shot film that broke most of the rules by introducing filmgoers to an antihero and a darker setting.

The next obvious Best Picture wouldn’t occur again until 1955, when controversial director Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront once again changed the direction of filmmaking.

The crime drama was a departure from previous works in the genre by introducing a new moral foundation to the setting while reinforcing Brando as a major new acting talent.

On the Waterfront beat the brilliant Caine Mutiny but was hailed a classic from its opening night and remains one of American cinema’s greatest ever films.

The 1950s and early ’60s were filled with strong Best Picture winners but arguments could and have been made for many of the films they defeated. Bridge over the River Kwai beat the revered 12 Angry Men in 1958, West Side Story beat the Paul Newman classic The Hustler in 1962 and even the much-lauded Lawrence of Arabia may have been lucky to beat the timeless To Kill a Mockingbird in 1963.

It wasn’t until 1968 that a lock came again when In the Heat of the Night claimed top honours. Norman Jewison’s masterful study of racism in the Deep South, which holds up impeccably even when measured against modern sensibilities, beat a strong field comprising Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, yet it remains one of the least controversial decisions in Oscar history.

Along with To Kill a Mockingbird, it set the mark for future serious films on a subject that had been barely touched just a decade earlier.

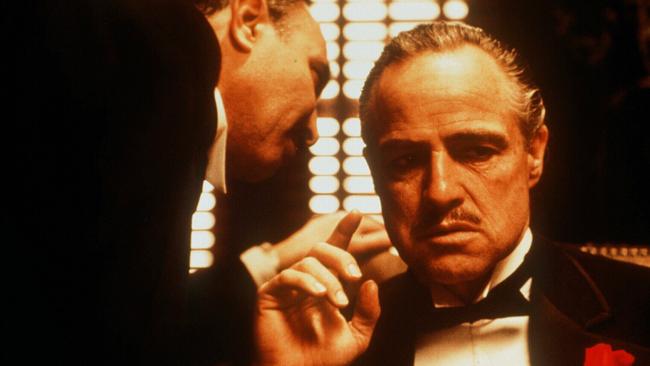

Which brings us to 1973 and the film many believe is the greatest ever made. The Godfather was a certainty from the time the nominations were released, despite the fact it was up against the eight-time Academy Award winner Cabaret (still the record number of Oscars for a non-Best Picture winner) and the flawed masterpiece Deliverance. The Godfather brought together a stellar cast, with Brando ultimately winning the 1973 Best Actor gong as Mafia family patriarch Vito Corleone, Al Pacino in his breakout role as his ultimate successor, future Oscar winners Robert Duvall and Diane Keaton and legendary actor John Cazale.

Running almost three hours, The Godfather once again changed our attitudes towards cinema and spawned a sequel that won the coveted award just two years later.

To cap it off, it achieved a 4000 per cent return on investment at the box office.

Only film snobs would argue against Rocky being named Best Picture in 1977. It beat the revered Taxi Driver, Network and All the President’s Men but stands up better than all of them almost 50 years later. Moreover, it features probably the best script ever written for a sports-based film, one of the greatest characters ever put to screen, and became part of our culture.

With apologies to the harrowing and brilliant Midnight Express, Deer Hunter was always going to be a certain winner in 1979 and once again, Oscar got it right.

The three-hour study of working-class friends enthusiastically heading to Vietnam before enduring the horrors of war earned Oscar nominations for Robert De Niro and Meryl Streep (her first) and garnered the Best Supporting Actor prize for Christopher Walken.

The 1980s were full to the brim with controversial choices, with winners such as Gandhi, Terms of Endearment, The Last Emperor and Driving Miss Daisy all beating vastly superior films. At least the decade got off on the right note, with Ordinary People delivering a sensitive, intelligent story and exceptional performances to defy the usual Oscar bait and win the 1981 top award.

If the 1980s were a wilderness for great Oscar winners, the 1990s soon rectified it. The Silence of the Lambs remains one of the most obvious choices in cinema history, with brilliant storytelling and a frightening theme delivered by compelling Best Actor and Actress performances from Hopkins and Jodie Foster.

And if Silence of the Lambs was a good thing in 1992, then Schindler’s List was an absolute certainty two years later. Regarded as one of the finest films ever made, Steven Spielberg’s black and white 195-minute Holocaust epic based on a novel by Australian writer Thomas Keneally would have won almost any year in film history.

It’s hard to find a lock for Best Picture in the 21st century, with almost every year featuring a wide-open race. Argo, Moonlight, Green Book, Crash, CODA, The Shape of Water, The Hurt Locker and Parasite were all controversial choices for one reason or another – usually because critics considered one or more films at least their equal in their given year.

The exceptions are The Departed and No Country for Old Men. One of acclaimed director Martin Scorsese’s best films, The Departed brought together Jack Nicholson in his last great role alongside superstars Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon. The following year, the Coen Brothers’ reached their artistic zenith with a riveting crime thriller featuring one of the most disturbing villains ever put to screen.

Rated by some critics as the best film of the decade, No Country follows sociopathic hit man Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem in an Oscar winning role) as he ruthlessly goes about tracking down a drug deal gone wrong.

In the past five or six years, the best film has been a particularly controversial choice. That either indicates the Academy got it wrong – which it has done more times than we can count – or the depth simply made the contest an open race. The Shape of Water controversially won in 2018 at the expense of Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. Green Book beat out BlacKkKlansman, A Star is Born and Roma in 2019 and the following year Parasite ousted The Irishman and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Whether or not the winners were worthy, they were certainly not obvious choices.

That pattern is set to continue this year, even though Everything, Everywhere All at Once is a short priced Best Picture favourite. Despite its apparent claim on the top award, its popularity is clearly momentum-driven. One month ago, the absurdist dramedy wasn’t even a favourite, with that position held by the Spielberg faux autobiography The Fabelmans ahead of Martin McDonagh’s The Banshees of Inisherin.

With the highly acclaimed Top Gun: Maverick and Avatar: The Way of Water also in the mix, this year’s winner is unlikely to be remembered as a standout. The same could be said about this year’s Best Actor prize.

Comeback star Brendan Fraser is a warm favourite to claim honours, largely for his transformation as a morbidly obese gay man in The Whale – which ticks several boxes for Academy voters. He is up against Colin Farrell in superb form but the Irish actor is playing an unremarkable fictitious character which rarely grabs the attention of voters, and Austin Butler portraying no less a real-life character than the immortal Elvis Presley. No matter who wins, there will be a hard-luck story.

The same should not be said about the Best Actress category – but it just may be. Dual Oscar winner Cate Blanchett is favourite to win her third statuette playing an orchestra conductor in the psychological drama Tar, but the film has received some predictably trite backlash for daring to portray a gay woman in a questionable light. If the criticism continues, Michelle Yeoh could pull off a minor upset as the central character in Everything Everywhere and become the first Asian winner of the award. ■