Car chases are a key component of virtually every action film released. If you have an action movie, you have to have a chase.

A really great chase takes more than just fast cars and spectacular smashes. It needs tension, realism and great acting.

Over the years there have been a series of fantastic car-chase sequences, but a handful are easily better than the rest. Here’s the best, in order of year of release.

Let us know your thoughts in the comments — what did we miss? What shouldn’t be here?

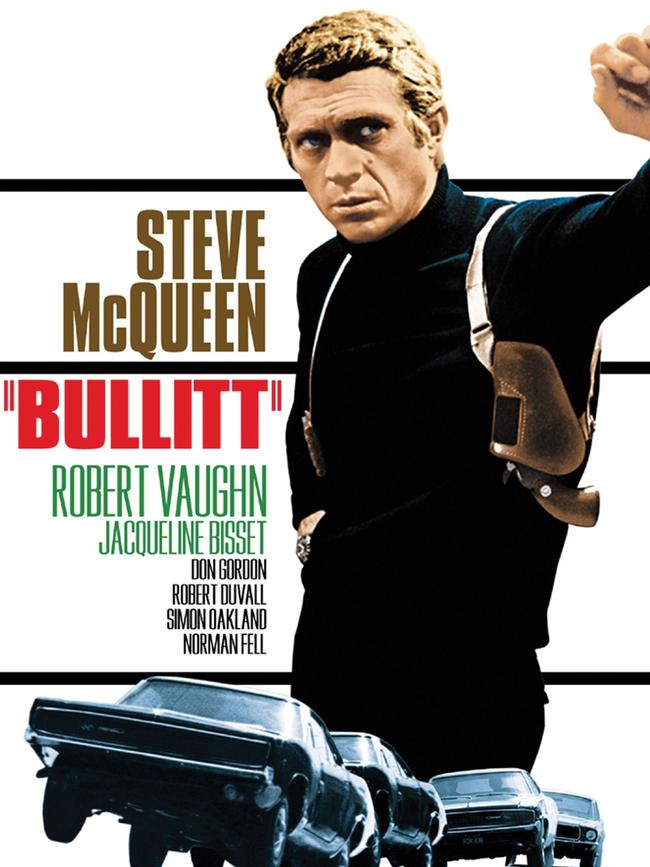

Bullitt (1968)

The grandfather of the car-chase scene, and often considered the best ever filmed, Bullitt’s 10-minute chase broke new ground for its gritty realism and stunt driving.

Filmed on the streets and highways of San Francisco, the city as much a part of the chase as the cars themselves, Steven McQueen — who drove the car himself for the close-up scenes — chases a pair of hitmen.

For viewers in the late 60s, must have been a total shock. Those POV shots put you right beside McQueen as his car tears down San Fran’s hills.

Bullitt’s chase is great because it didn’t fake anything. Lots of long takes. A car even hits one of the cameras. They reached tops of 180km/h. There’s no music, no dialogue, just the roar of the Mustang and the Charger.

That really is the famous San Fran staircase they go down, which is as much a feat in itself.

But the real hero is the seamless editing, which won the film an Oscar. And that ending.

Did you know? In early 2017, one of the original Mustangs used in the film was found in a Mexican junkyard — 50 years after it was last seen.

WATCH IT: Fetch | Google Play

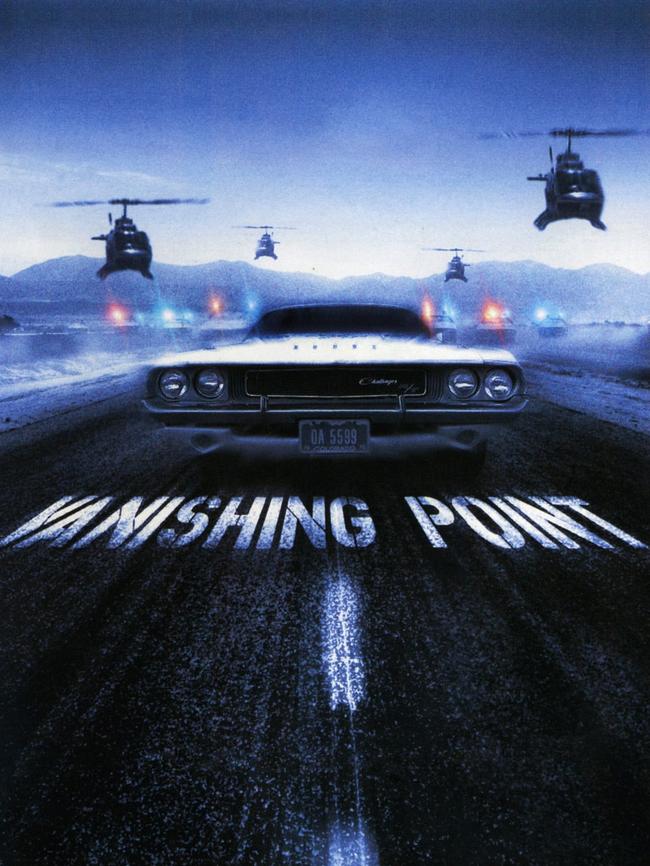

Vanishing Point (1971)

There isn’t one great chase in Vanishing Point — it’s virtually all chase.

Kowalski is a driver with a suitably dark, heroic past, and he’s supposed to drive a 1970 Dodge Challenger from Colorado to San Francisco (about 1900km) in one weekend to deliver it to a new owner.

When you’re going that far that quick, you’ll attract attention. Most of the film is a series of stunning chase-and-crash set pieces as Kowalski outruns motorcycle cops, police cars, helicopters, crazed locals and jumps creeks.

There’s one short respite — a bizarre few scenes in the desert with some snake-loving churchgoers (look, it was the 70s).

His journey is noticed by a blind, black DJ listening to the police scanner who broadcasts the chase, and soon the national media pick up the story, creating a frenzy of interest.

Vanishing Point is one man’s middle-finger against authority, a single-minded rebellious ex-cop burning rubber along America’s empty highways with no real purpose other than to rebel.

It’s a film about freedom, even under authority, as a man who knows it can’t end well refuses to give up control, and about public voyeurism as people gather to watch his ride.

WATCH THE TRAILER

Did you know? Five Challengers were used — and all were returned to Chrysler, with no blown engines.

WATCH IT: Good luck finding it to stream (legally) but DVD copies abound.

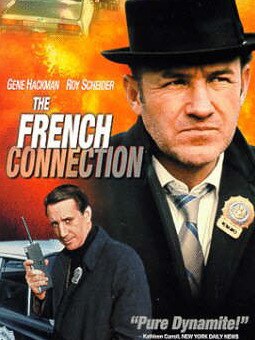

The French Connection (1971)

This film is incredible. Wait, let’s display that properly:

This film is incredible

Crumbling and freezing, New York is as much a character as the people are here. Dark buildings tower over the actors, we’re constantly in back alleyways, with rubbish strewn everywhere.

Set against all this cold and filth is Gene Hackman’s alcoholic detective Popeye, a violent, ruthless narcotics cop, determined to bust a drug ring.

This isn’t the usual chase. Instead of car v car, director William Friedkin sets Popeye against an elevated train, chasing a sniper who just took a shot at him.

He drives angry, dodging traffic and pedestrians, desperately trying to keep up with the train — and the last link in his case — the chase developing into a full-on, jarring sequence, without effects or music, set against a developing hostage situation on the train itself.

Filmed without official permission, the filmmakers had police shut down the streets and clear traffic lights, but several times the chase ended up in other streets, forcing the car to evade other vehicles and pedestrians who had no idea the film was being shot.

All of that is included — even a part where a man heading to work was hit by Hackman’s car.

Somehow, this grim, grimy movie won the Oscar for Best Picture, and Hackman won Best Actor.

Did you know: Friedkin filmed the chase himself from the back seat, because the other camera operators had wives and children, and he didn’t.

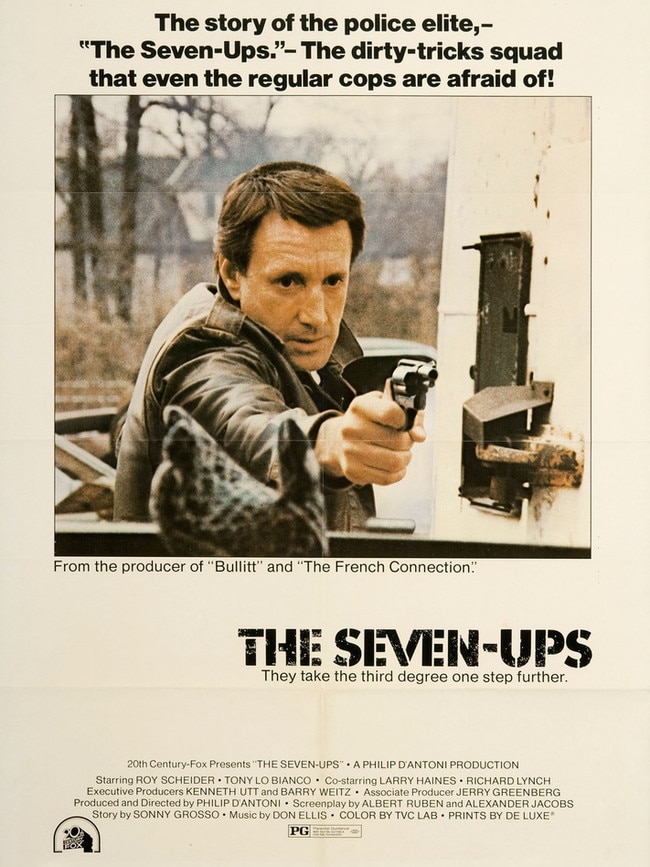

The Seven-ups (1973)

Not so well-known these days, Seven-Ups follows Roy Schneider’s NYPD detective character Buddy Manucci as he investigates his partner’s death and discovers a kidnapping ring. It’s another classically-70s, gritty police drama, this time with a near 10-minute chase sequence, mostly around New York City.

Legendary stuntman / driver Bill Hickman, the bad guy who drove in Bullitt (and unseen in The French Connection), flees as Schneider gives chase, sparking a long sequence around the streets of upper Manhattan — including an incredible wide-shot slide around 5.35m, which highlights just how real this chase was.

Everything’s real here. When that door is ripped off, a camera crew standing just out of shot was nearly injured. Every expression on actor Richard Lynch’s face is real as Hickman floors his 1973 Pontiac through a crowd of kids.

The camera cars barely keep up, and the chase comes to a sudden, brutal ending.

Did you know: Directed by Philip D’Antoni, who produced Bullitt and French Connection

WATCH IT: Again, hard to find streaming but you might find it at your local library

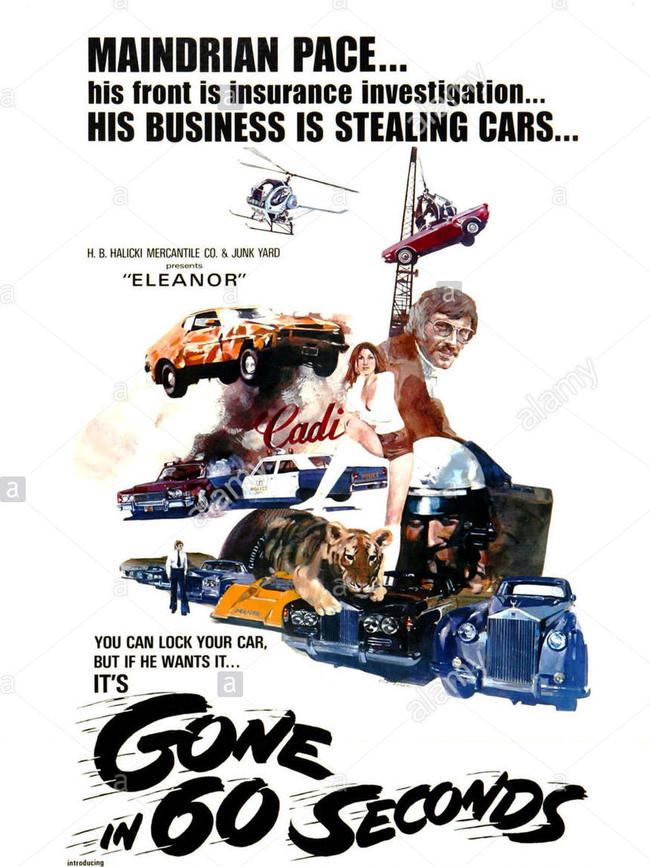

Gone in 60 Seconds (1974)

No, not the Nicolas Cage remake, this is the original — a truly independent movie written, produced, directed and starring a now-legend in low-budget filmmaking, H B Halicki, who was killed in a stunt while filming the sequel.

Featuring a six-city, 40-minute chase sequence that destroys 93 cars, this movie — and especially this chase — is the stuff of legend. Honestly, it’s virtually unbelievable. (I’ve written too much about this already, because, it’s just incredible.)

The leader of a car-theft ring, he has to steal 48 specific cars in five days for a huge sum — as long as they’re insured. Then he’s double-crossed, setting up an epic chase sequence, the longest in cinematic history.

Halicki came up with ingenious ways to film some bone-rattling crashes, doing all his own driving and stunts, dodging pedestrians, malls, crowds, police cars, trucks, and driving on virtually every road surface available.

You couldn’t film this today, not this realistically. Cars slide across the road, people flee. It’s complete chaos, pure, utter insanity put to film. Unscripted collisions were edited in — if something looks too real, it probably was.

It’s amazing he survived this film at all. He was badly hurt when his car spun into a light pole at 160km/h. The first thing he asked in the hospital was if they’d filmed it. The crash made the final cut.

The final jump scene at the end set a standard most filmmakers wouldn’t try for these days without CGI or a gas-propelled catapult. Halicki suffered a spine compression in that stunt and never walked the same again.

Halicki made two more similar films, which are both worth watching, especially The Junkman — in which he tried to top this chase.

Please enjoy the utterly ridiculous original trailer:

Did you know: Filming would stop for days at time so Halicki could repair and restore cars at his junkyard business to earn more money for production.

WATCH IT: Amazon Prime | Tubi

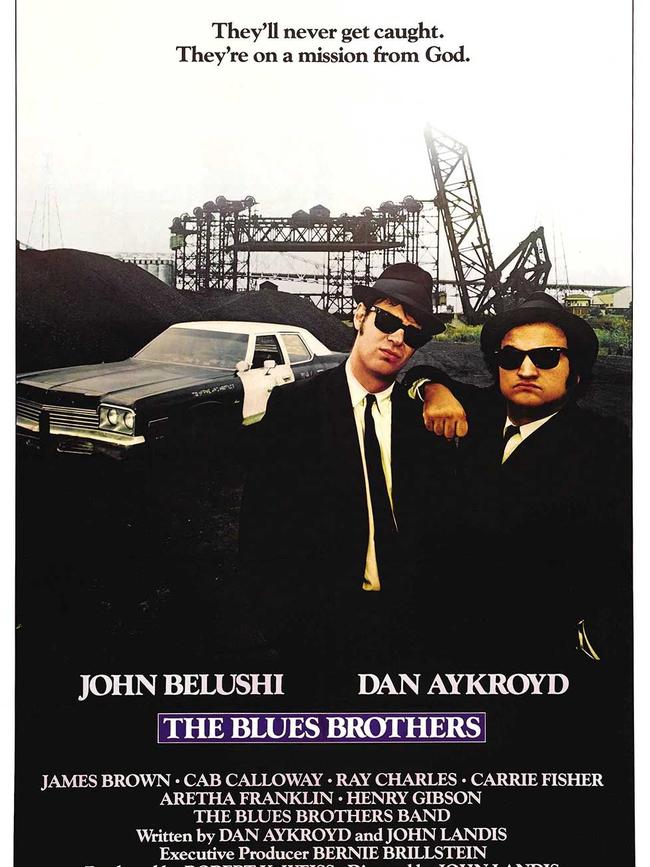

The Blues Brothers (1980)

Maybe the best thing about The Blues Brothers is its realism, its integrity, interspersed with a bizarre otherworldliness. It’s another one that, were it made today, it would be completely different.

Consider: Dan Aykroyd had never even read a screenplay when he wrote this movie. John Belushi was constantly bombed on cocaine and kept disappearing during filming. It was about religion and blues, in an era of disco and rock. There’s a bit where the Head Sister magically glides backwards. It’s really, really long.

The Blues Brothers shouldn’t have been this good.

It’s a musical comedy with a paper-thin plot built largely to allow for brilliant performances, and TWO insane police chases. Which one’s best? Take your pick.

Is it the utter demolition of a shopping mall, for no real reason other than they could? Or the 120 MILES per hour down Lake Street in Chicago? It wasn’t sped-up film – John Landis reshot that part of the chase with stunt pedestrians visible to prove it.

Then there’s the music. The studio didn’t want James Brown, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin — their careers were on the downturn. It wanted younger, up-and-coming discos stars. Aykroyd was insistent on using the legends.

The Blues Brothers works because of contradictions — Jake and Elwood maintain steely, unsmiling personas while still clearly moved by the music, and God, in the face of overwhelming opposition.

WATCH THE FAMOUS PILE-UPS HERE

Did you know? There’s a great Lego version of the mall scene.

WATCH IT: Binge

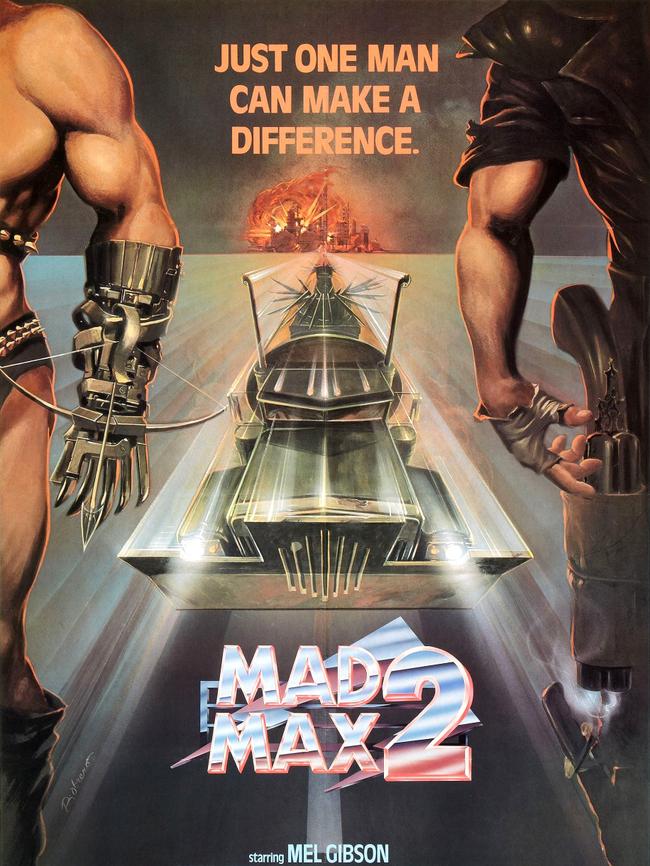

Mad Max II (1981)

A bona fide action classic, Mad Max II is one of the best Australian films produced, and one of the greatest sequels of all time.

From the post-apocalyptic look to the stunning stunt work, this is the real deal — no CGI, no wires, no effects.

Max returns as a quasi-hero, alone on the road, and ends up helping a community of settlers in their fight against petrol-hungry marauders.

Mad Max II includes two great chases, but the final petrol tanker sequence is the brutal standout.

A roaring, thunderous battle that includes a child in peril, ridiculous stunts, huge smashes, all at top speed, it’s a berserk piece of cinema — inventive and thrilling.

Just remember — there are no special effects. When Wez, one of the chief marauders, smashes his bike into a crashed car, that’s a real person spinning through the air. In fact, not only did the stuntman break his leg, the frame is slowed in the final cut to make it easier to see. There’s a great featurette that shows how they filmed that bit here.

Did you know: The driver of the tanker wasn’t allowed to eat in the 12 hours leading up the highly dangerous final crash, in case he needed emergency surgery.

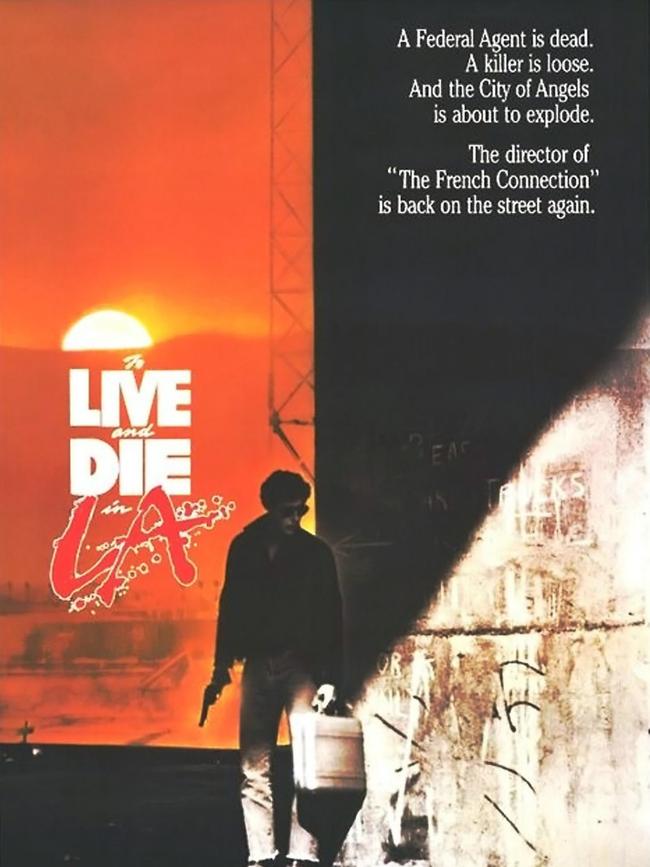

To Live and Die in LA (1985)

The director of The French Connection (see below) didn’t want to do another car chase unless he could top it — so here’s the sun-bleached 1980s version.

Corruption and obsession collide in Los Angeles as a US Secret Service agent chases a murderous, sleazy counterfeiter, who killed his partner (just three days from retirement, no less).

William Petersen is the relentless, amoral agent — in fact, it’s hard to find someone with actual morals in this movie — and he really doesn’t care what he has to do to bring down Willem Dafoe’s counterfeiter.

The chase, which took six weeks to film, is eight minutes of mayhem, but it’s very different to the French Connection.

Here our ‘heroes’ are the ones being chased, and much of the action takes place off the street, down railway lines, in trucking yards and water culverts before heading the wrong way down a busy LA freeway — a cinematic first. Many of actor John Pankow’s back-seat reactions are real.

Did you know? Director William Friedkin came up with the idea of sending the chase down the wrong side of the freeway years before, when he fell asleep while driving and did just that.

WATCH IT: This one doesn’t appear to be stream in Australia anywhere at the moment – you might have to go old-school and get the DVD.

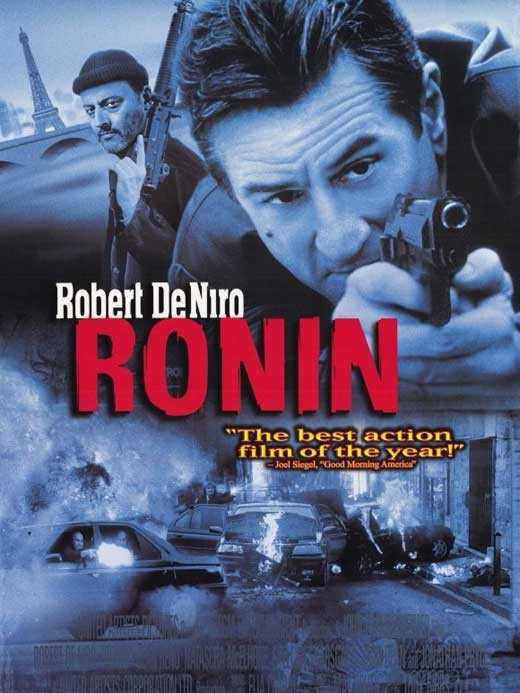

Ronin (1998)

A world-weary Irish woman assembles a group of experts from dubious backgrounds, ex-spies and Robert De Niro to steal a mysterious briefcase from a bunch of guys with guns — a few double crosses later, the Russians and Irish are after them.

Ronin’s a return to the spy thrillers of the 60s and 70s, even set in Europe to make it more authentic. We’re given two car chases, filmed on location through the streets of Paris, the second of which is remarkable for its realism and speed.

It’s shot live, by legendary director John Frankenheimer, with no digital effects, no music, and no dialogue. Everything you see is real.

Constant point-of-view shots create a sense of unrelenting momentum as the two cars drive head-on at high speed into oncoming traffic, causing multiple pile-ups and mayhem. You forget it’s all staged and planned.

Part of what sets Ronin’s final car chase above many others is that many of the actual actors were in the cars during the chases, mimicking the stunt drivers’ actions with fake steering wheels, so their reactions are completely real. De Niro really is hurtling down narrow Paris streets at huge speeds — and he really is freaked out about it.

Did you know: About 80 cars were purposely destroyed in the chases, with more than 300 stunt drivers used.

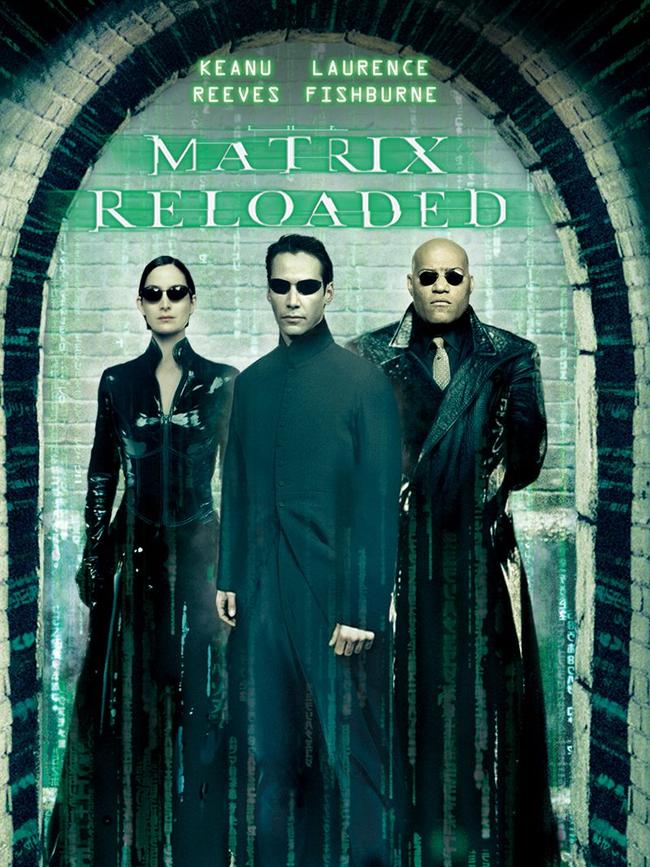

The Matrix Reloaded (2003)

The Matrix was a massive hit, hugely influential in style and special effects. To follow it up, the Wachowskis had to go bigger, supercharge an already overcharged movie.

Reloaded was overwhelmingly massive — but arguably not better.

When I sat down to write this, I couldn’t quite remember what the sequel was about. It’s that kind of movie. Zion’s under attack, and there’s a Keymaker, and an Architect and a Source, or something.

Whatever. It’s got a crazy-great freeway car chase — for which the Wachowskis built an actual 2.2km-long freeway on an old naval base. That alone cost them $4.5m in Australian dollars. It was destroyed afterwards.

So, they were pretty serious about making a solid chase.

For a Matrix movie, it’s surprisingly light on CGI. Overhead shots give you the true scope, while in-car shots and highly stylised slo-mo put you in the action.

It’s edited into two sections — the second a wrong-way chase on a motorcycle, back up the freeway.

This part is brilliantly edited, as the motorbike dodges and scrapes past cars and giant trucks with inches to spare.

The chase culminates in a huge head-on collision between two semi-trailers, and has some very mid-2000s CGI. You should probably watch it now.

Did you know: The chase sequence took three months to film, longer than many films’ entire shooting schedules.

WATCH IT: Foxtel Now

The Bourne Supremacy (2009)

Patching up a gunshot wound with vodka? Check. Reading Moscow street maps as you outrun the cops? Check. Taxi able to sustain shocking damage against a hulking, impenetrable Mercedes 4WD? Check.

The second Bourne film’s car chase is about five minute of pure perfection, utterly ridiculous but truly cool, and far darker (literally) than the first film. Even the sky is greyer. Hey, it even ends (abruptly) in a tunnel.

In the first Bourne film, Jason was in a Mini. The tone was lighter, nearly comedic in comparison. The chase was earlier in the movie. This time around he’s in a vulnerable taxi and the car chase is the film’s climax — and it shows.

Filled with super-quick edits, great sound and a host of perfectly timed escapes and crunches through dirty, grainy Moscow streets, the chase is immediate and frenetic.

It’s action cinema for a new generation, as Bourne tries to escape a multitude of Moscow police cars and a very frowny KBG agent — and manages to engineer a truly fatal ending.

Did you know? The chase sequence won two World Stunt Awards, for the driving and overall stunt co-ordination.

WATCH IT: Binge

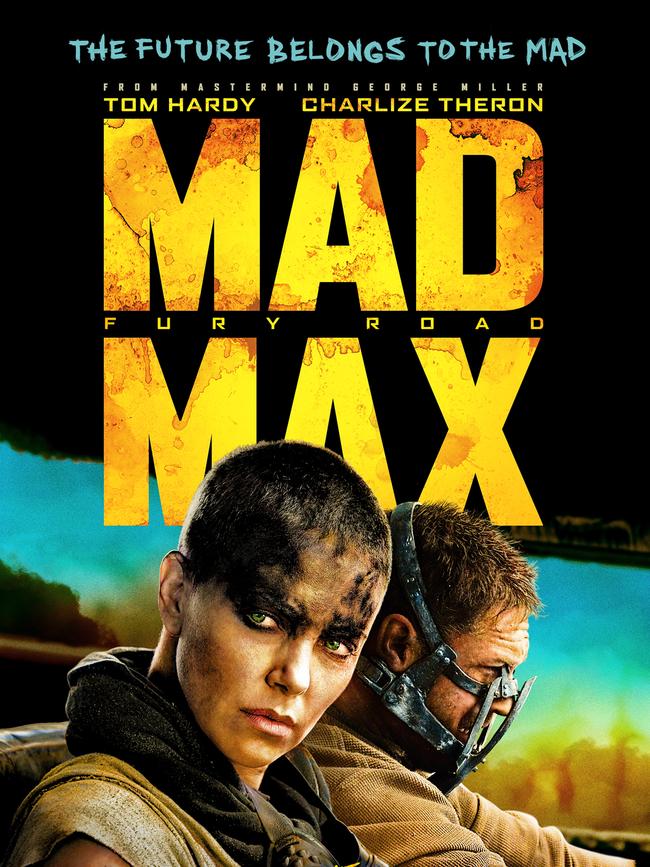

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

You have to be pretty confident in your filmmaking abilities to make a movie that’s pretty much just one long, relentless chase sequence.

George Miller raised the bar with his earlier Mad Max movies — but set a new standard for action movies in general with Fury Road.

In a way, it shouldn’t work. The plot is thrifty. All they do is chase for a while, have a short rest, then turn around and go back.

Despite that, Fury Road is arguably the best action movie of the decade, and genuinely hard to stop watching.

It’s utter spectacle, mayhem on an epic scale, with its gripping stunts that just get bigger and bigger, glorious use of colour, and a complete disregard for movie rules — a ‘hero’ that doesn’t speak for half the movie, a whole bunch of female warriors, editing that goes against the customary Hollywood quick-cuts. The CGI was used to fill in the background. All those smashes and stuns really happened.

Buried within all that explosive noise is Miller’s brilliant examination of the cult of car worship, as a bunch of blokes chase after their ‘breeders’, who bring it all down around them in a desert wasteland. Now, that’s really not Hollywood.

Did you know? Edited by Miller’s wife, Margaret Sixel, to make it look different to other action films. She won an Oscar for her work.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout