Dragons R Us: Mythical messengers always come with a riddle

DRAGONS: We’re fascinated by them in Game of Thrones — but the appeal of these fire-breathing beasts resonates deep in our history and our future.

DRAGONS. We’re fascinated by them in Game of Thrones. But the appeal of these fire-breathing beasts resonates deep in our history — and our future.

They’ve been lurking in the background. Quietly waiting. Growing stronger.

Game of Thrones, which launches this week into its seventh season, has played on this sense of power-filled suspense.

That tension is as much a part of the eternal appeal of dragons as is their strength, their nobility — and their deep political and religious symbology.

Flinders University lecturer in English and Creative Writing Dr Erin Sebo says the mythical creatures tease our deepest fears.

Famine. Fire. War. Theft. Oppression.

But we’re not totally terrified of them.

Instead, there’s an element of hope buried among their formidable folklore forms.

They’re understandable.

RELATED: Game of Thrones ultimate fan guide

SONGS OF FIRE AND ICE

Dragons have until now played a relatively minor — but ominous — role in the enormously popular book and television series.

That’s not unusual for dragons.

In most Western myths and legends they sleep, fitfully, in caves beneath castles and mountains. They stir only when someone comes too close, or if portentous events unfold above them.

Their mythical roots embody our fear of the unknown. Of unseen threats. Of uncontrollable forces and unpredictable principalities.

“G.R.R. Martin emphasises their otherness as well since they are, in many ways, out of place in a world which thought dragons were gone,” University of Sydney PhD student in Old Norse and Old English Robert Cutrer says. “The Targaryens are re-emerging from obscurity and bringing the ‘legends’ of the past back with them.”

Dr Sebo says she sees the allure of dragons to be distinctly different from our modern fascination with vampires, zombies — and White Walkers.

GAME OF THRONES? Our own history is just as brutal, and it has dragons too

“The interest in vampires in the last decade or so seems to me to stem from the fact that they are outside nature,” she says.

“They mirror our attempts to separate ourselves through medicine and technology from ageing and illness, as well as from basic things like having to eat food in season or stop work when it gets too dark to see.”

Dragons, however, are at the opposite end of our spectrum of fears.

“I think that in a world where the greatest dangers are global, things like climate change and economic collapse, things that are complex and can only be addressed through massive international co-operation in implementing complex policies, the idea of only having to fight and kill a fire-breathing dragon feels like a relief,” Dr Sebo says.

BURNT INTO OUR MINDS

A dragon may be awesome but its elements are understandable.

It is simple. It is manageable. Its threat can be countered.

And the simplicity of this threat could be why winged serpents resonate in cultural memories the world over.

“Oddly, what strikes me is that people really aren’t all that terrified of dragons,” Dr Sebo says.

“We should be; they are lethal non-mammals and people usually have a more pronounced reaction to non-mammals. We are disgusted by slugs and terrified of even small spiders but there is a tendency to anthropomorphise dragons. People respond to them as beautiful and majestic.”

Nobody knows when, where or how dragons entered our folklore.

Some speculate that memories of living animals and exposed fossils may have inspired the first legends.

We know a Chinese historian from the 4th century BC recorded the remains of a “dragon” in Sichuan province.

It’s most likely to have been a fossil of a tyrannosaurus, stegosaurus — or maybe even the yi qui (bat dinosaur). It’s also likely others stumbled upon similarly fearsome fossils elsewhere in history.

Then there’s the magnificent might of Egypt’s formidable Nile crocodile.

Some can grow up to 18m in length. Historically, some roamed far afield — such as the Mediterranean island of Rhodes (as one tale by the Knights of St John attests).

And the tale of such sightings no doubt grew taller with the telling.

But dragons embody the terror of giant snakes, huge eagles, lions, lizards … all of which have been programmed into our innate survival instincts.

“At the end of the day, the dragons of romances are chimeras,” Cutrer says.

“They are made ‘other’ by fusing many things together.”

DEVILS INCARNATE

Western culture embraced the concept of dragons early, and they held a particularly strong place amid the evolution of Christianity.

“Medieval bestiaries list dragons along with other exotic creatures and sometimes even include information about their symbolic association with the devil,” Dr Sebo says.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of AD793 details ‘dreadful forewarnings … whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament”.

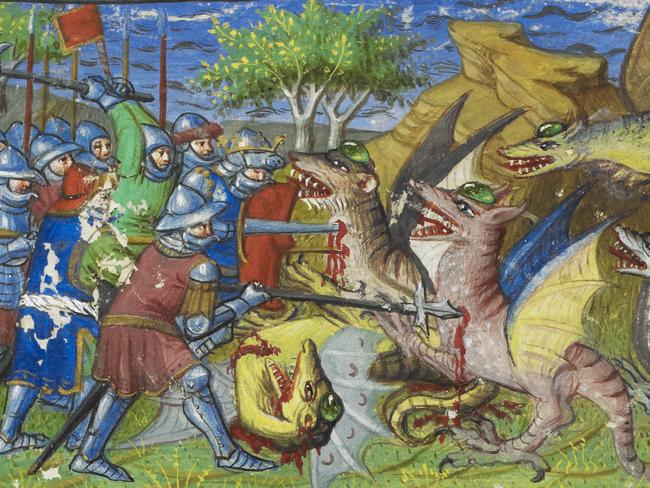

Stories of dragon/devil slayers such as St Michael the Archangel, Margaret of Antioch and St George were just as popular as Game of Thrones in the Middle Ages.

While their mysterious but beautiful forms filled medieval manuscripts for centuries as symbols of spiritual evil, they were also sometimes portrayed as guardians of wisdom.

In fact, the word ‘dragon’ comes from a Greek word meaning ‘to watch’, or ‘gleaming of the eye’.

“The dragon shifted from the supernatural to the fantastic through the popularity of romances which often removed the religious symbolism and left the tale with a stereotypical monster,” Cutrer says.

“This is also when, in Western literature, they started flying and breathing fire — or shooting it out of their eyes. The monster became more of a Chimera, a mixture of different animals, that everyone saw as fictional rather than symbolic of Satan.”

SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST

Western dragon tales have long since evolved away from the demonic world.

“Secular early medieval dragons are rarer than you might think,” Dr Sebo says, “and yet it is this tradition that most modern fantasy literature draws on, mainly because Tolkien and C.S. Lewis used these dragons as models for their writings.”

These tales can be found etched deep within rune stones and epic poems dating from the 8th and 9th Century AD.

Smaug of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit is drawn from the mythical beast Fafnir and the dragon of Beowulf. Eustace in C.S. Lewis’ Voyage of the Dawn Treader is probably inspired by those found in the Icelandic Gull-Þóris saga.

“Fafnir is a shapeshifter and he talks and plays at riddles,” Dr Sebo says.

“But the ‘Thrones’ dragons (at least so far) seem defined by the fact that they are very unhuman.”

Mr Cutrer argues the secular medieval dragons were morally simple. “They are monsters,” he says.

”Fantastic dragons in the middle ages lack a personality at all. They exist only to be a delay in the romance.”

And George R.R. Martins’ incarnation?

“While his world is very influenced by Tolkien, his dragons seem more influenced by the popular tradition of Dungeons & Dragons — which has dragon eggs (not in Tolkien or medieval texts), and gives them a fairly developed life-cycle.”

FUTURE FEARS

The symbology of dragons is as strong now as ever.

And while some of the fears they represent have changed, others have not.

“The inherent problem of dragons as seen by scholars like Grimm and Tolkien is hoarding — a refusal to co-operate. It is still incredibly relevant with the fear of consolidation of wealth and selfishness,” Cutrer says.

And then there’s their ‘otherness’, their unnatural combination of natural elements.

Ethicists are tackling the concept of ‘building’ a dragon through DNA manipulation to explore the issues — and limitations — facing the gene-editing technology CRISPR.

And the science journal Nature published a 2015 ‘April fools’ article by Australian academic Dr Andrew Hamilton, who argued “anthropogenic effects on the world’s climate may inadvertently be paving the way for the resurgence of these beasts.”

It was a coy commentary on the climate change debate. But the apocalyptic power of the dragon would have drawn the eye.

“The general trend in literature is that humans will be the cause of their destruction, a trend that really started with the advent of the nuclear age,” Cutrer says.

“So the threat of CRISPR and global warming really fits into those fears that we will be responsible for creating whatever destroys us.

“Modernism loves this view, whereas the medieval world wouldn’t give man so much credit. Dragons definitely reside now in the realm of man-made disaster and can symbolise the realisation of the worst traits in man.”