‘Chin up, girls. I’m proud of you and I love you all.’ It was one final pep talk before unimaginable slaughter – and just one harrowing moment in an extraordinary tale of survival.

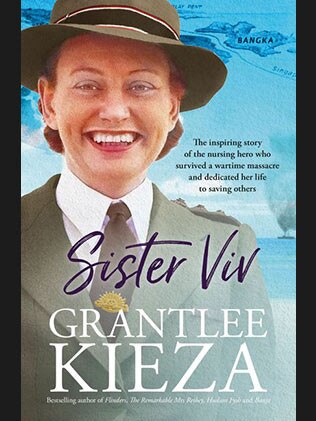

Vivian Bullwinkel is one of the most-recognisable names from Australia’s World War Two story. In his stunning new biography of the Army nurse, GRANTLEE KIEZA sets her life against the momentous events of the last century – from her birth during World War One, through her ordeal as a wartime prisoner, to her final mission into a conflict zone: Vietnam.

This edited extract from Sister Viv begins after Vivian and her fellow WW2 nurses are ordered, against their wishes, to abandon their patients and flee as the Allied fortress of Singapore falls to a merciless, murderous foe. Their journey will end in one of the most notorious atrocities in our history.

In addition to the extract, scroll down to:

- see moving animations and hear Vivian describe the Bangka Island incident.

- experience an immersive Anzac360 video explaining Australia’s role in the battle for Singapore.

- watch author Grantlee Kieza on the “heartbreaking” experience of writing Sister Viv.

FEBRUARY, 1942: The heat from the oil fires all around Singapore was so intense that Viv and the other nurses had to shield their faces with their bags. The naval base at Seletar had been set alight when it was abandoned. Black rain from the oil and showers of sparks covered Viv’s clothes.

Thousands of distressed parents carrying small children swarmed at the gates to the docks waving documents and passports in the faces of the military guards, begging for a berth on the ships. The guards ushered the nurses through but thousands of others began to realise there was no escape from the Japanese, who were snapping at their heels.

One group of terrified men began rushing through the crowd, knocking everything in their path out of their way in a mad, desperate scramble to board a ferry bound for the ships in the harbour, but the military police drew their revolvers and opened fire. Viv could hardly comprehend the carnage as some of the men were shot dead and the others with them, perhaps brothers, stood stunned and mortified. Others in a panic stepped over the bodies and started waving their passports again.

Then a Japanese aircraft came hurtling across the sky just above the huge crowd and dropped bombs into their midst, tearing bodies apart and ripping away large pieces of timber and concrete from the wharf. Viv saw frantic mothers holding pieces of what had been their precious babies, and small children wandering around as though in a trance calling for mothers and fathers who had likely been killed.

Viv and the other nurses rushed into the sea of bleeding humanity to do what they could, ripping apart clothes from abandoned suitcases to use as bandages and tourniquets to treat severed limbs and shattered bones. All the time they knew that with the Japanese so close and the hospitals already overflowing, most of these wounded people would die. Viv was ministering to a young woman who had been wounded in the air attack when she saw a well-dressed young man only a few metres from her sitting forlornly beside the body of a dead woman. Gently he rolled the body over and from underneath it picked up a baby the mother had been shielding from the Japanese blasts. With tears rolling down his face he cradled the baby to his chest and, without a backwards glance, left the dead woman where she lay and joined the queue hoping to find a place on one of the boats.

Over the next two days, forty-four ships fled Singapore with evacuees on board. But a large Japanese naval force was anchored at the head of the Bangka Strait directly in front of them. Despite the best efforts of the skippers leaving Singapore, all but four of the ships would be bombed and sunk. There were not only ships fleeing Singapore but every type of craft that floated – two-man canoes, 12-foot skiffs from the Singapore Yacht Club, sampans, open cargo boats called tongkangs that were powered by oars, sails and punt poles, private launches, junks, pleasure yachts, tugboats of every description, and small coastal vessels. Most of them never made it to safety either. Thousands of men, women and children would die before any could reach land.

Viv and her fellow nurses board the SS Vyner Brooke, an overcrowded peacetime steamer trying to thread through the islands around Singapore to reach safety – but Japanese planes attack, bombing it then repeatedly strafing the survivors in the water.

BODIES floated beside dead fish, oil drums, and the contents of suitcases that had been burst open by the explosions. About fifty people had died in the attack, though no one would ever be really sure, because the ship had fled Singapore crowded with desperate people and there was no time to keep an accurate record of the passengers’ names.

While the Japanese bombing raids had ceased, there was the ever-present threat of attack from below. Sharks, including aggressive bull sharks and huge tiger sharks, hunted the seas around Sumatra. Blood in the water and the constant movement of the shipwreck survivors’ legs could only mean trouble. Jimmy Miller tried to put everyone’s mind at ease by saying there wouldn’t be a shark within 20 miles of the area, given the number of bombs the Japanese had dropped. Still, everyone was sure they’d be much safer on Bangka Island if only they could get there.

Vima Bates, the vibrant redhead, who had helped Viv look for wounded passengers only an hour or two earlier, was floating alone on a life raft, but in the powerful currents that seemed to change direction rapidly, she drifted away from the main groups of survivors and was never seen again. Betty Jeffrey swam past Win Davis and Pat Gunther, who were clinging onto a canvas stretcher. She saw that a number of life rafts had been lashed together, and non-swimmer Olive Paschke was among a group of oil-soaked nurses on them.

The nurses decided that everyone should take turns at swimming and helping to push the makeshift raft along. The only person on the raft who refused to have a turn in the water was imperious German Annamaria Eleanor Goldberg who, despite being a medical doctor, seemed to have little sympathy for the sick and injured. She and her husband had been interned as enemy aliens in Singapore and accused of spreading anti-British propaganda.

With a heavy German accent, Dr Goldberg told the others on the raft that she would not budge. ‘I am more important than any of you,’ she said. Veronica Clancy lifted herself out of the water and half onto the raft and punched Dr Goldberg, who screamed defiance but still refused to move. Blanche Hempsted decided to go tagteam with Veronica and grabbed Dr Goldberg in a headlock, dragging her backwards into the water, and telling her to kick with her feet like everyone else.

Eventually they make it to land on Radji Beach, Bangka Island, where they meet another group of survivors and debate what to do, before deciding to surrender.

VIV knew some of her nurses and wounded men would die if they didn’t receive proper medical help soon – and in a hospital.

Surrendering to the Japanese was a risk, but what else was there to do? She had heard all the horror stories of their cruelty. When the soldiers, airmen or sailors had come into hospital at Tampoi and Singapore, they had told her with looks of horror that ‘the Japs are not taking prisoners’. It didn’t matter what branch of the service the Australians were in; the warning was always the same: ‘They’re not taking prisoners.’

‘However when you’re young,’ Viv recalled, ‘and you’ve got a group of over a hundred people you can’t imagine anything happening, and we confidently felt that we would be taken prisoners because of safety in numbers.’

What Viv didn’t know was that Captain Orita Masaru and his men from the 229th Regiment, those same soldiers who had murdered and raped their way through Hong Kong on Christmas Day, had just arrived on Bangka Island as well.

One of the party locates some Japanese soldiers and brings them to the beach. But instead of taking the evacuees prisoner, they first round up most of the men, march them around a headland and begin executing them.

VIV trembled at the sounds of more shots from behind the headland and, all around, the group of nurses hung their heads at the realisation of their fate. Japanese soldiers stood guard over them, smirking. There was hardly a sound from any of the captives. Five minutes passed. Then the execution squad reappeared, climbing over the rocks of the promontory before sauntering back to where the nurses and the badly wounded lay.

As they approached they were laughing among themselves.

‘Bully,’ gasped Jenny Kerr, who was standing behind Viv, ‘they’ve murdered them all.’

Viv felt helpless and devastated, not just for her own life and that of her friends with her on this beach, but also for those dear young men Jimmy Miller and Bill Sedgeman, who had fought so hard to save the lives of all those aboard the Vyner Brooke, and who had done such a sterling job getting them to what they thought was the safety of Bangka Island. Those brave men had risked their lives to save the nurses and now those lives had been forfeited.

Lainie Balfour-Ogilvy whispered to the others that they should all just run – run for their lives. They could scatter, bolt in different directions and at least some of them might escape. The strong swimmers could dive into the water, dodge the bullets and swim to another beach or another part of the jungle to get away.

However, Matron Drummond reminded her girls that there were many badly wounded people, including their nursing colleagues, lying in stretchers behind them, and their duty was to always help the sick and the injured. Abandoning their patients went against everything they stood for.

So, huddled together under the merciless gaze of their Japanese captors, the nurses prepared themselves mentally for the horrific reality of what they were about to face.

Indifferent to the suffering of their forlorn captives, the young Japanese soldiers who had killed the men behind the headland now marched to a spot in front of the nurses and knelt down.

They began reloading their rifles and using rags to clean the blood from their bayonets. Another soldier set up a light machine gun underneath the palm trees about 20 metres from the beach.

‘It’s true then,’ Nancy Harris mumbled. ‘They aren’t taking prisoners.’

Viv and her desperate friends readied themselves to fend off their tormentors as best they could. Everything became a blur. Eventually, Viv heard Masaru snap an order and his soldiers formed a semicircle around the nurses.

They were about 10 metres from the water’s edge. Viv tried to comprehend the end of her young life and of those all around her. Everything became chaotic and jumbled. Were the soldiers tearing at the nurses’ clothes? Were her friends being beaten and sexually assaulted? The savagery of what was unfolding made Viv numb. The soldiers made the nurses turn to face the sea and form a line. Old Mrs Betteridge was weeping in the middle.

The soldiers kept prodding the sharp tips of their bayonets into the quaking backs of the women, making them walk falteringly towards the water that was gently lapping at their feet amid the unfathomable violence on Radji Beach.

Viv tried to shut out the awful horror of this living nightmare.

She thought she heard Jean Stewart cry out: ‘Girls, take it, don’t squeal.’ At the far right of the line Irene Drummond was also quietly telling her girls to be brave.

Viv’s mind was in a whirl, and she wasn’t sure what she heard or what she thought she heard. She knew she was standing on the far left of the line with Jenny Kerr and feisty Alma Beard, and her brain registered Alma saying: ‘Bully, there are two things I’ve always hated in my life: the Japanese and the sea. And today I’ve ended up with both.’

Viv was looking out across the water. Somewhere out there lay Australia and home. How can something as obscene as this be happening in a place that is so beautiful? she wondered. What right do these men have to do all that they are doing to these marvellous young lives?

Some of the women were praying aloud, intoning ‘Our Father, who art in heaven …’ and ‘Hail Mary, full of grace …’

A sense of calm came over Viv. She was thinking that at least it would be lovely to again see her father, George, in heaven and to prepare a place for when her mother and brother, John, joined them there one day.

Then she thought of the shock and grief her mother would feel back home, not knowing what had become of her. She saw her mother’s shining blue eyes and, in her mind, they seemed to tell Viv that they would see each other again and they would share carefree days as they had growing up in the Australian bush.

Viv thought she heard Matron Drummond, who was a few paces behind, give one last pep talk to the nurses: ‘Chin up, girls. I’m proud of you and I love you all.’ Viv turned to the others along the line and smiled one last goodbye at them. Some of her friends returned her smile. Some had an unbreakable inner strength. But some had already decided they were not prepared to leave this world just yet, and when they reached the water’s edge they turned and ran as fast as they could. But they were cut down.

Irene Drummond was a few metres short of the water as the other women shuffled into it. One of the soldiers shot Irene in the back and she slammed head-first into the water. Her glasses flew off her head and as she instinctively groped for them, a second bullet tore through her. She did not move again.

The machine gunner then cut loose, spraying the women in the water, those standing stoically, those screaming in fear, those supporting the wounded who could not move without help.

All along the line Viv saw those beautiful women, full of heart and kindness, being cut down, flopping into the sea as bullets blasted them from behind. Some fell limp, face first; others folded and crumpled. There were cries of anguish and terror all about.

Viv was waist deep in the water and preparing herself to step through the gates of heaven and see dear old Dad again. Such was her trance-like state that she could hardly hear the rifles and the machine gun barking.

Then Viv felt something like the ‘kick of a mule’ hit her in the back and she too fell face forward into the water. Everything turned to black. The Japanese bullet had torn through the flimsy grey fabric of her dress and ripped through her body. Her lifeforce gushed out of her in a red stream, mixing with the blood of her friends in the water that was gently lapping on the golden shore of Radji Beach.

***

AS Viv floated among the blood and the bodies of her friends and prepared to expel the last breath of her short life, the Japanese soldiers went about killing anything that moved in the water. With Captain Masaru supervising, the soldiers plunged their bayonets through any of the nurses who had survived the gunshots. But Viv floated a few metres out to sea away from the bodies of her friends. As far as Masaru was concerned, she was as good as dead.

The Japanese bullet had entered Viv’s back on the lower left side and exited her stomach about 5 centimetres above her fabric belt. In a remarkable understatement she later said: ‘I was very surprised to find myself still alive.

‘I was young and naïve, I thought that when people were shot they’d had it. I was utterly amazed a few seconds later to find that I was still alive, and then I became frightened and I thought, “Oh, God, I can’t go through that again”. I just lay there and, because I had swallowed a whole lot of salt water, and was starting to become violently ill, I thought, “Oh, they’ll see my shoulders moving, they’ll see my shoulders moving”, and I stopped, and I just laid there.’

And so Viv lay in the water, face down as she drifted out to sea. The Japanese left her body to drift away as shark bait.

Viv didn’t know it, but the Japanese soldiers killed everyone else on the beach, mostly with their bayonets. Some of the nurses who had tried to run had been shot down or had been bayoneted or beaten to death with rifle butts. Then Masaru and his men went about slaughtering all the wounded on stretchers, before going to the nearby fisherman’s hut to kill all the badly wounded who were resting there. When the killing spree was done, the Japanese soldiers disappeared into the jungle to cause mayhem elsewhere.

Time seemed to stand still as Viv drifted in and out of consciousness. Eventually, the gentle, rhythmic waves carried her to the shore, where the beach was littered with what remained of her friends.

The sun on her back was warm, but she still felt an icy fear and the cold spread through her body. Her medical training told her it was shock setting in. She thought about finding a nice, warm place where she could curl up and die. But then she began to regain her senses and became deathly afraid.

She remained face down on the sand and let the tide run over her again and again and again. The bullet wound was excruciatingly painful, but she gritted her teeth and stayed motionless, listening to the waves, the screeching of the birds and the wind whispering through the palms.

Sixty-five Australian nurses had left Singapore on the Vyner Brooke just four days earlier. Thirty-three were now dead.

• Sister Viv by Grantlee Kieza will be published by HarperCollins on April 3

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Dirty trick killed Aussie sport icon

An Australian sporting hero was slain by enemy deception, at the moment of victory in a legendary battle still celebrated today – after a premonition of his own death.

Love story behind horror ordeal

The last survivor of a horror shipwreck reveals the untold story: ten days adrift, stranded on a remote Aussie shoreline, mates dying around him – and the love story behind it all.