Tarnanthi exhibition rewrites photography from an Indigenous viewpoint at Art Gallery of SA

Past and present photographs of remote Indigenous community life paint very different pictures as part of this year’s Tarnanthi exhibition.

Arts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Arts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Many hands make light work at Tarnanthi exhibition

- Queer artist’s self-insemination project loses funding

There is a wonderful juxtaposition of photography in Open Hands, this year’s Tarnanthi exhibition which surveys contemporary Indigenous art around the nation.

From Australia’s northeastern tip on Cape York, Naomi Hobson takes contemporary images of young people to tell new stories of her changing community from its own perspective.

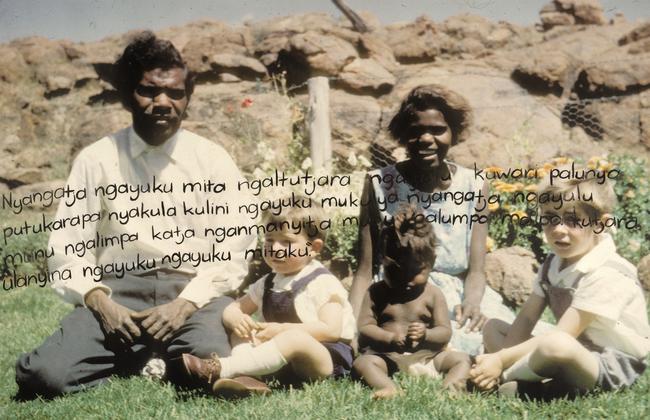

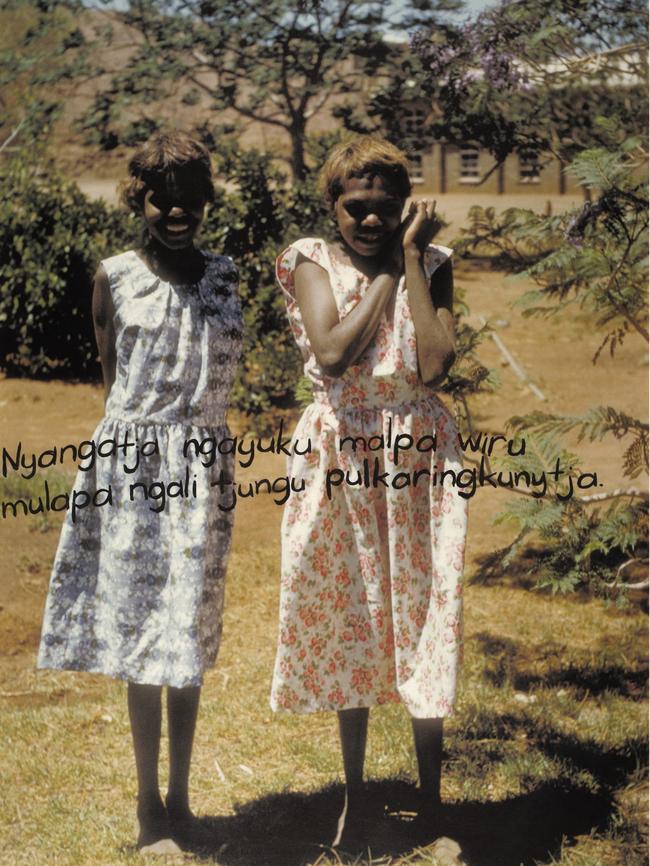

On the other hand, closer to home, senior Anangu artist Nyurpaya Kaika Burton literally rewrites the stories of families from South Australia’s remote APY Lands captured in archival photography, by handwriting across them in her Pitjantjatjara language.

Open Hands pays tribute to senior artists – in particular women artists – who pass on vital cultural knowledge to younger generations as their peoples’ future leaders. The exhibition, which also spans painting, moving image, sound installation, weaving, ceramics and sculpture, opens this weekend at the Art Gallery of SA and runs until the end of January.

“I feel that a lot of our stories are not told properly – from the Indigenous side of the story,” says Hobson, a multidisciplinary artist of Kaantju and Umpila descent, at her home in Coen, a small community of 364 people at the upper reaches of Cape York.

Hobson, 42, is mother to three teenage daughters – around the same age as the subjects in her Adolescent Wonderland series of photographs – and is motivated by storytelling.

“With my photographs, it’s time for the world to see who our young people really are,” she says.

“The camera captures all that – the pride in our young people, in community, who they are as young Indigenous Australians and what they stand for, where they come from, what they believe in and what they represent … their individuality.”

To reach other communities on the uppermost reaches of Cape York, Hobson says visitors must first pass through Coen.

“A lot of people come in and take photographs, and they want to see the Aboriginal people all dressed up and painted up in mud, wearing the grass skirts, and that’s what they take away from visiting Cape York.

“We still have that – that’s who we are – but our young people are in touch with the world today. They are savvy around technology. Through Adolescent Wonderland, it’s showing who they are as individuals. They do have their culture, they do participate in ceremonies, they still speak their language, but they’re not of the old world. They’re not of the new world, but they’re carving their own world.”

That shift between worlds is heightened by Hobson’s decision to print the background locations of her images in black-and-white, while saturating her human subjects and the objects they interact with in vivid colour.

“I put the effect on it because I wanted all young people to find a relation or a connection to the young persons in the photographs. So it doesn’t matter what background or where you come from … it’s highlighting their differences, their uniqueness, their individuality,” she says.

“By putting the light on the young people in the photographs, is helping other young people then to find that connection within themselves: Be proud of who you are, where you come from, your background, your heritage, your beliefs. Embrace that.”

Tarnanthi artistic director Nici Cumpston says that photography is “reframed” by Hobson.

“Photography has a long history as a colonising agent, used to measure and define Aboriginal people and to record their incarceration, but for Naomi it is simply a means of presenting the colourful daily life in her community,” Cumpston says.

“Free from the ethnographic gaze or the physiognomic trace that often lingers in photographs of Indigenous people, her series Adolescent Wonderland is characterised by the abiding traits of trust and candidness.

“This intimate familiarity is possible only because Naomi is an insider – a member of the community and a friend. Her characters play to the camera, empowered by it rather than objectified.”

Hobson’s interest in photography grew from supporting herself as an artist by getting a part-time job with the Cape York Land Trust.

“They gave me a camera – the Land Trust had me going out and just photographing the mob working on country. They said, ‘We could do with someone recording some of the work we do’. They gave me this beautiful camera and I had to learn how to use it quick. Every time the rangers would go out and do a certain project, I was asked to tag along and photograph it. It just sort of developed from there.

“It was by accident that I brought it home.”

Hobson would also photograph community meetings, where she first noticed the young people who were participating.

“What was really striking was the outfits that they would wear along to the meetings, and their way of engaging in the community meetings. It was like, wow, you young people have a lot to offer.

“I felt that their story needed to be heard – because a lot of the time, the decisions in community are made by elders.”

Meanwhile, Anangu artist Burton works on enlarged, pigmented digital prints of archival photographs taken of families – and in particular children – from the APY Lands.

“In one work by Nyurpaya, an archival photograph of young children (including the artist herself) shows the group sharing stories by mark making on the ground,” Cumpston says.

“A description of the scene is inscribed in the artist’s hand across the photograph – an act by which Nyurpaya renounces the archive and affirms the performative, eternal present.”

Burton grew up at Ernabella Mission, which was established in 1937 by the Presbyterian Church on the former Ernabella Station in the Musgrave Ranges. In 1974, the community itself took over administration through the Pitjantjatjara Council, and it was renamed Pukatja.

“We used to live in a wiltja (shelter) far away from the homestead,” recalls Burton, who was born in 1949. “When I got older I started going to school. We were all naked, poor things. No clothes, even on cold, windy days when it rained.”

Burton says those experiences growing up continue to inform her artwork today.

“When I’m drawing this, I’m thinking back to those early days – living on bush tucker, eating and living together, happy, with our families. Strong, with no sickness.

“And we would listen to stories, everyone talking. When we tell funny stories, we would laugh. And when we tell sad stories, we would all feel sad and sorry, poor things.”

Tarnanthi: Open Hands, Art Gallery of SA, until January 31, 2021.