Arts reviews: Inked, A New Brain, Swan Lake and The Garden

Read our reviews of Inked, A New Brain, Swan Lake, Theatre Republic’s The Garden and The Dictionary of Lost Words.

Arts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Arts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

University of Adelaide Theatre Guild

Little Theatre

October 12 to 22

Inked takes a look at an extraordinary year in the life and times of newspapers the world over.

It features the renowned Rupert Murdoch, as he took Fleet Street by storm and set his sights further afield.

The reinvention of the struggling broadsheet The Sun into a market-leading tabloid is a wild ride indeed. It’s a ripping yarn, and the production by the University of Adelaide Theatre Guild is outstanding.

Joshua Caldwell gives Murdoch confident swagger, while Bart Csorba’s performance of The Sun’s editor Larry Lamb is arguably the best turn this already excellent actor has yet produced.

An excellent cast, 15-strong, and including many of Adelaide’s finest, are intelligently directed by Robert Bell and Rebecca Kemp. It’s a giveaway that talent of this calibre, cast and crew, have stormed the doors to get in on this show.

Ink is a long haul, nearly three hours, but completely absorbing, powering on relentlessly. The time flashes by, and is utterly well spent.

Peter Burdon

A New Brain

Star Theatres

October 13 to 21

It’s often the case that an artist’s own experience is their greatest source of inspiration. So it was for US composer William Finn when, back in 1992, he experienced a life-threatening medical episode requiring brain surgery. A few years later, the musical comedy A New Brain was the result.

Finn, probably best known for the splendid The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, can certainly write a tune. In A New Brain, he writes no fewer than 30 of them! The songs run the gamut of music theatre, and many of the catchy tunes, complex rhythms and clever internal rhymes are up there with the best.

The sophistication of much of the music demands a crack team, and director David Gaucci has secured some fine voices in the lead roles. Daniel Hamilton (Gordon, our suffering composer) has made a big impact in a short time in Adelaide. Adam Goodburn (Mr Bungee, a children’s performer for whose TV program Gordon composes songs) has been a stalwart in the opera scene for many years; Catherine Campbell (Gordon’s mother Mimi) of cabaret fame; Lindsay Prodea (Gordon’s lover Roger) and more.

The sheer number of songs and their variety risks unevenness in the delivery, but Gaucci times it well, giving space when needed, and powering on when the story demands it.

There are some deliciously funny moments, many of them involving Mr Bungee, whose cheery green costume barely conceals a grumpy, jaded hack, and Gordon’s overweening mother Mimi – who gets the song of the show, the power lament Music Still Plays On, sung superbly by Campbell. A six-strong band under Peter Johns do great justice to a substantial score.

A New Brain is an ideal piece to celebrate David Gaucci and Davine Productions 10th anniversary. The excellent Mr Gaucci has brought consistently good and interesting productions to the community, and congratulations to him for doing so.

Peter Burdon

The Australian Ballet

Swan Lake

Festival Theatre

October 7 to 14

The Australian Ballet’s 60th anniversary production of Swan Lake opened with a nine-performance season practically sold out, and expectations were predictably high.

The production is a “reimagining” of the hardiest perennial in the company’s garden, Anne

Woolliams 1977 version, which is as much cerebral as artistic, with an almost anthropomorphic approach to the swans, and an occasionally Pavlovian response from the humans for good measure!

It comes as a surprise to audiences familiar with Graeme Murphy’s radical 2002 account and

Stephen Baynes neo-romantic tragedy from 2012.

The revival is tinged with some new choreography by AB alumnus Lucas Jervies and an entirely new design. Given it was already a group effort, with the great Ray Powell supplying some of the dances, it’s now a multi-generational piece.

The Adelaide opening night was good, if not great. The big scenes in Act 1 were shaky, the unisons approximate, and much movement was obscured by the voluminous costumes from US designer Mara Blumenfeld. Our Siegfried, Joseph Caley, missed an early landing, and took a time to settle.

It also went for a long time, with this version including much that is often omitted, and in truth, the story of Prince Siegfried’s passion for the beautiful Odette – the finest and most consistent performance of the night from Benedicte Bemet – only becomes clear at the very end of the act. That said, his pining solo is a poignant moment.

Act 2, the first in the evil sorcerer Rothbart’s woodland realm, is much more confident, with the 24-strong corps of radiant, glittering swans in stark contrast to the minimalist set, really little more than a suggestion of trees. Here the razor-sharp precision that is needed was firmly on show in the ensemble numbers, the much-loved “Dance of the Cygnets” and more.

We return to the castle, all gilt and filigree, with the popular foreign dances, all lavishly costumed. It’s a second outing for the scene-stealing jester (Marcus Morelli) and here our Siegfried hits his straps, now with the bewitching Odile. Then finally it is back to the sparse forest lake, where the swans are radiant, in spite of Rothbart’s cruel spell, and our star-crossed lovers accept their fate.

All told, this production doesn’t quite gel – at least, not yet. The movement hasn’t settled, and the music is too slow by half. Even the redoubtable Adelaide Symphony Orchestra seemed tentative under new AB Music Director and Chief Conductor Jonathan Lo.

That said, it’s a worthy effort.

Peter Burdon

Theatre Republic

The Garden

Space Theatre

October 11 to 14

The relationship between local independent Theatre Republic and local playwright Emily Steel is a rewarding one.

The company’s premiere of her How Not To Make It In America a couple of years ago was a case in point, and their latest collaboration, The Garden, makes it two for two.

The neutrality of the promotional material for The Garden belies the punch it packs. We’re told that Evelyn is the coordinator of a community garden, and doesn’t know quite how to handle the inquiring Adam, hoping to be their newest member. But not this garden’s typical member. He’s black! He speaks with an “African” accent! But he is well dressed, and has a job. How can this be? Is he really “their” sort of person?

Evelyn is an awful character. Her world is one of institutionalized and embedded privilege. Her feeble effort to ignore or overlook the colour of Adam’s skin is a dismal, discomforting failure. All she does is constantly remind him that racial identity is everything. Unless, of course, you’re white. Her condescending, arrogant, racist remarks are not entirely borne out of ignorance.

Adam’s story ought to be entirely unremarkable. He arrived in Australia as a refugee – by plane, after a 10 year wait. He works, pays his way, saves some money, dresses well. Nothing to see, you’d think. Unless, of course, you’re black.

It takes actors of some mettle to take on roles like these, and Rashidi Edward and Elizabeth Hay are terrific. Hay, in particular, takes on an irredeemable character, yet somehow manages to invest the audience in Evelyn to the extent that we can learn from her mistakes.

Director Corey McMahon’s deft touch is especially evident in the terrific timing, not just of words and actions, but of silence and stillness. Meg Wilson’s delightful set, all planter boxes and garden beds, is an island of calm in an often turbulent pond.

Peter Burdon

The Dictionary of Lost Words

Dunstan Playhouse

September 27 to October 14

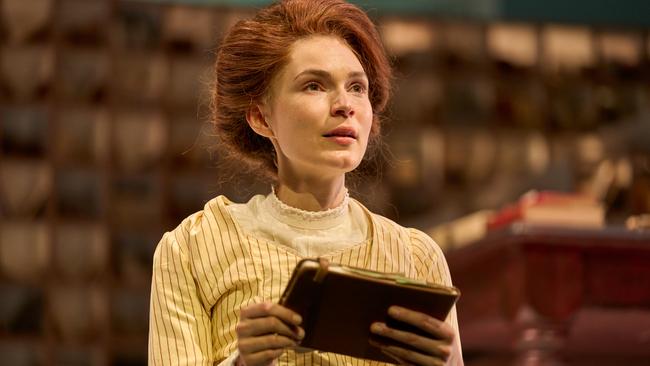

When the word got out that Pip Williams’ hugely successful The Dictionary of Lost Words was to be adapted for the stage, the talk of the town was, simply, “How?”

How can a story that spans a hundred years and more, from poverty and squalor to wealth and luxury, from rarefied intelligentsia to epoch-making social change, be condensed into something manageable, or even comprehensible?

To her lasting credit, Verity Laughton has done just that, weaving a wondrous tale that somehow manages to touch on the many themes of the novel, while fleshing out, in prodigious depth, the complexity of the character at the centre of it all.

She is Esme Nicoll, precocious in childhood, and ever more focused and determined through adolescence and into adulthood.

Her inquisitive nature, and boundless love for words – and deep understanding their power – is brought to life by Tilda Cobham-Hervey in a performance that is both mesmerising and exhilarating for its intensity, scale and focus.

There are so many precious moments, like the discovery of her first lost word, Lily, the name of the mother she never knew who died giving birth.

A word that was to be discarded from the world-leading task of compiling the Oxford English Dictionary for want of a reliable definition. But it has a meaning to her.

There are moments of discovery, moments of experience for the sake of it, and for the unexpected impact of love.

There is so much to say. Esme is surrounded by a fine cast, many doubling and tripling up, directed with keen insight by Jessica Arthur.

Jonathon Oxlade’s set is a bibliophile’s dream – hundreds, thousands of small notes that combine to create the famed Dictionary.

The Dictionary of Lost Words is a must-see. In a first for State Theatre, the entire season sold out before opening, with every effort being made to finds some extra seats. If you can get one, do it. It’s unmissable.

Peter Burdon

Ilya Gringolts, violin and Aura Go, piano

UKARIA

September 24

The concert program at UKARIA is a remarkable succession of musicians of the highest calibre.

It makes you wonder where we would be without it – how many artists of international renown would come to Adelaide were it not for the opportunity to perform at this unique venue nestling on a hillside in the picturesque Adelaide Hills?

Violinist Ilya Gringolts is a violinist at the peak of his profession. His program covered the classics – Mozart and Schumann – with a contemporary work by Wolfgang Rihm, which in this context was like thorns amid the roses.

It is complex, at times violent, but also intensely lyrical and evocative. The performance was absolutely gripping from start to finish.

The exquisite high harmonics emerged from Gringolts’ Stradivarius with absolute purity. Intense bursts of energy gave way to passages of neo-Romantic wistfulness.

In this very demanding piece pianist Aura Go was with Gringolts all the way, in a truly engrossing performance.

Mozart’s expansive Sonata in A major was performed with admirable clarity, perfectly balancing energy and elegance.

Schumann’s even more (perhaps too) expansive Sonata in D minor was full of impetuous passion and vitality, capturing the essence of the Romanticism that Wolgang Rihm’s work had earlier paid homage to by pulverising it.

Stephen Whittington

David Garrett – Iconic

Her Majesty’s Theatre

September 22

David Garrett walks on to the stage to a rock star’s welcome and he leaves with a standing ovation.

He’s carrying a named Guarnerius del Gesu violin almost a century older than the city of Adelaide. It has a luscious tone and clarity all the way to the extremes of its range.

Garrett draws out sweet melodic lines and moments of great passion to the delight of the audience.

He’s supported on stage by guitarists Franck Van Der Heijden and Rogier Van Wegberg in some very effective arrangements. Their ensemble playing is a delight.

While he’s billed as the world’s greatest violinist this is not a program aimed at the classical music audience.

It’s a banquet of cupcakes and while he names such virtuosi as Heifetz and Kreisler this menu of two dozen little pieces is the music they played as encores after major recitals.

The young violin students in the audience at least get to see that there is another career path if they wish to continue playing.

This is part of his first Australian tour. He’s a prolific recording artist and YouTube personality and will certainly be welcomed back any time.

He’s unlikely ever to stand in front of the Adelaide Symphony and play a full concerto, though the violin itself deserves a chance to show what it is truly capable of creating.

Ewart Shaw

Priscilla, Queen of the Desert

Gilbert & Sullivan Society of SA

Arts Theatre

September 21-30

The Gilbert & Sullivan Society has a solid gold hit on its hands with its dazzling – and bedazzled – production of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

Director Gordon Combes and his enormous cast have a field day from the pop of the first champagne cork to the triumphant finale.

In case there’s a living soul who doesn’t know the story, Priscilla is a bus containing two drag queens and a transgender woman travelling from Sydney to Alice Springs.

Their adventures – and misadventures – during their Outback trek are rightly the stuff of screen and stage legend.

But the story, grand though it may be, goes for nothing without the right cast, and in the leads, we have a spectacularly talented trio, led by the incomparable Vonni, who inhabits the role of Bernadette.

A former Les Girls star herself, Vonni is the first transgender woman to play the role, which she’s already done in a 2022 main stage production. Her Bernadette is a deft mix of world-weary cynicism and big-hearted love.

Her travelling partners Tick and Adam are played to the hilt (and then some) by Billy St John and Benjamin Johnson, both of whom are clearly revelling in their outrageous, larger-than-life roles.

The minor roles and ensemble – no fewer than 28 of them – are up for every challenge, and every costume change. And all hail to the eight-strong costume and wig team. Praise, too, to the 10-strong orchestra, playing up a storm.

This spectacular production deserves full and screaming houses. It’s the best fun this writer has had for ages.

Peter Burdon

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

September 22 and 23

Mark Wigglesworth is a conductor who makes very intelligent choices.

This program’s first half comprised Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 1 and Grace-Evangeline Mason’s The Imagined Forest (2021) in its Australian premiere and his tight rein on the ASO’s sonic resources ensured 35 minutes of deliciously refined and modulated orchestral sounds, almost in the manner of a chamber ensemble.

But after interval Sibelius’s Symphony No. 1 beckoned, a marvellous old warhorse full of Nordic mists and big tunes, and the cat was truly out of the bag.

The Town Hall rafters rang with tumultuous tuttis, flaming brass and tremendous percussion, yet Wigglesworth was everywhere, coaxing a shape here, a solo there, always ensuring clean clear balanced sounds with a superior musical edge.

His choices were so well targeted.

Ilya Gringolts, violin soloist in the Prokofiev, proved an engaging and indeed riveting figure armed with a wonderfully broad palette of dynamics especially within the softer ranges.

He was always empathetic to the orchestra and yet commanded attention and lead the musical way in this early neoclassical work.

Here was a performance that successfully captured Prokofiev’s elusive melange of ethereal moments set against his trademark acerbic rhythmic drive all encased within a delicate exterior.

Mason’s The Imagined Forest, a work Wigglesworth already knows well from previous performances overseas, cleverly maintained momentum while simultaneously allowing listeners to appreciate its greenery.

Mason projects a formidable presence through the composition’s tensile strength and sensitive beauty.

Rodney Smith

Macbeth

State Opera South Australia

Her Majesty’s Theatre

September 7-16

This Macbeth is a truly striking achievement. As the overture begins, the play of shadows on the empty stage is foreboding.

Those tall pillars will be trees and walls, as they slide across the platform. Those shrouded figures are witches.

Finnegan Downie Dear directs the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, skilfully negotiating the jaunty passages and the explosions of the brass.

The tension is heart gripping. Director Stuart Maunder equally balances the pageantry and battles with the intimacy of the Macbeths’ relationship.

Scene after scene is unforgettable. Shakespeare would have loved it.

Verdi and his librettist Piave go full-on 19th century Italian opera. Three witches? Let’s have 18. Three murderers? Throw in an extra dozen or so.

There’s a big drinking song, and impressive ensembles, the one on the death of Duncan being particularly memorable.

The State Opera Chorus, ably marshalled by Anthony Hunt, sink their teeth in with gusto. There are regimented soldiers, desperate refugees and sword fights courtesy of Jo Stone.

Jose Carbo, in his role debut, is an articulate but introspective Macbeth, putty in the hands of his ambitious wife. He grows in stature as the tale unfolds and is superb in the second act.

Nothing becomes his life like the leaving it. Kate Ladner’s Lady Macbeth is seductive in voice and manner, falling into despair, poisoned by her consciousness of guilt.

Pelham Andrews is unforgettable as the ill fated Banquo, sung as well as we have come to expect, and tender with Fleance his son, Elliott Purdie.

Against the tyrant stand the forces of good led by Paul O’Neil, whose lament for his murdered family is deeply affecting.

Tomas Dalton as Malcolm, runs to England for his own safety but returns late in the action at the head of the English forces. The two men put in heroic work.

There is fine supporting work from Teresa LaRocca as the Lady in Waiting and Nicolas Todorovic as the doctor, witnesses to Lady Macbeth’s madness.

Roger Kirk’s set design is infinitely flexible and his costumes, in a limited colour palette of black, silver and red have tartan accents, kilts, floor-length robes and heavy quilting on the armour.

Of special note are the robes of the Scottish Kings in Macbeth’s horrified vision. They are stained red to the knee: “I am in blood stepped in so far … returning were as tedious as go o’er”.

Ewart Shaw

Emily Sun in Recital: Storm and Sunlight

Elder Hall

September 9

Emily Sun and Andrea Lam’s recital lived up to its description.

The storm came in the form of Fazil Say’s dramatic second violin sonata Kaz dağlari (Mount Ida).

This work was inspired by the environmental damage caused by the Kirazli mine in Türkiye and the subsequent protests in 2019.

The first movement conveyed the destruction with repeated percussive figures on the piano accompanying an elegiac violin line, alternating with more aggressive rhythmic patterns.

Sun executed the plaintive violin bird calls of the second movement with exceptional control. The final movement, Rite of Hope, featured beautifully nuanced phrasing from Lam in the extended piano solo.

The sunnier moments in the recital were in Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun and a selection of Sibelius’s Six Pieces Op. 79.

There was excellent rapport between the performers in the three Sibelius pieces, with Sun’s warm tone and Lam’s finely-controlled balance adding to the stylishness.

The Debussy arrangement suffered in comparison to the original – the orchestra work is renowned for its innovative orchestration and plethora of instrumental timbres.

The version for violin and piano lost much of this richness, despite the sensitive playing from both musicians in this performance.

The recital ended with a tour de force rendition of Grieg’s third violin sonata.

Melanie Walters

Joyce Yang, piano

Elder Hall

September 6

Is the piano a keyboard instrument or an orchestra in a box?

Depending on how it is used it can be one or the other, or both.

In her performance of Guido Agosti’s taxing piano transcription of Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite, pianist Joyce Yang produced a dazzling array of vivid colours that were truly orchestral in scale.

Or at least produced the illusion of polychromatism – the art of playing piano is often an art of illusion.

This is a piece positively bristling with difficulties of all kinds, but one needs to do more than play all the notes, daunting though that is.

In her talk before the second half of her program Joyce Yang revealed that she is a synaesthete – she “hears” colours.

That may explain in part her ability to turn the piano into an orchestra (not a band) in a box. Certainly it was an extraordinary feat.

Elsewhere in the program, which was unusually structured, she was more tempered in her approach, although six Preludes by Rachmaninov had their fair share of colour.

Works by Tchaikovsky, Bach (arranged by Egon Petri) and Aaron Jay Kernis – an American little known here – demonstrated her fine command of the piano, although none of it approached the impact of the Stravinsky.

Stephen Whittington

Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill

State Theatre Company SA

Space Theatre

August 25 to September 9

Just a few months before her sad death in 1959, Billie Holiday gave a performance at a tatty Philadelphia bar that was to become the stuff of legend. Drunk and drug-addled, an electrifying performance was punctuated with tales tragic and true.

Lanie Robertson’s 1986 play is given a tremendous production by State Theatre.

Zahra Newman is unforgettable as Holiday. Her voice is a glorious instrument, superbly controlled, and uncanny in its likeness without being a straight-out impression.

The songs are a grand selection. Many of the classics are there: What A Little Moonlight Can Do, T’aint Nobody’s Business If I Do, and a powerhouse performance of God Bless The Child.

Others are there in snippets – the devastating Don’t Explain, for instance – as a falling star’s composure fails.

The play is not without its challenges. It’s a slow burn, with Holiday’s slurrings and swearings building from the occasional aside to a full-blown disaster as she strides angrily and aimlessly around the stage, cursing her lot, blaming the world.

The ramblings are sometimes laboured, but director Mitchell Butel imperceptibly – the mark of a really good director – charts a clear path forward.

Newman is backed by Kym Purling, one of Australia’s finest, on keys, with Victor Rounds (bass) and Calvin Welch (drums) in a performance that would sell out Carnegie Hall on its own.

And the set by Ailsa Paterson is yet another reminder of this great designer’s genius.

We’re truly privileged to have talent of this quality on our own doorstep.

Peter Burdon

Steven Osborne

Ukaria Cultural Centre

August 27

Pianist Steven Osborne is a superbly versatile musician, and rarely could that versatility have been better demonstrated than in this program which was very much a tale of two halves.

Collections of works by Schumann and Debussy in the first half meshed well to give listeners tonal beauty, sensitivity and balance, perhaps because excerpts from Debussy’s delightful Children’s Corner Suite were alongside the 13 pieces that form Schumann’s magnificent Kinderszenen.

Osborne was as insightful as he was light-footed in these delicious morsels.

But Rachmaninov awaited after interval with two Preludes and two Études-Tableaux moving into darker territory.

Their Slavic melancholy heralded a positively visceral performance of Rachmaninov’s Sonata No. 2 in one of its many incarnations, on this occasion by Osborne himself. Tumultuous hardly begins to describe it.

The three-movement work stems from a time when more modern compositions of Scriabin, Szymanowsky and others were proving enticing.

Osborne almost levitated as he threw himself into meeting Rachmaninov’s titanic technical and sonic demands. And although Rachmaninov’s memorable melodies, so beloved in his concertos, are wrapped around with dense chromaticism they were still there for Osborne to thunder or soar through.

By contrast Osborne’s Debussy and Schumann demanded total pin-drop focus from listeners and he got it. The Snow is Dancing whirled evocatively and The Poet Speaks never sounded more quietly intense and utterly moving.

I guess the real wonder is that one pianist can be so many things to so many people.

Rodney Smith

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

August 25

It’s not often that an orchestra performs the same piece twice at a concert.

I remember it happening with Stockhausen’s Gruppen, presumably because no one would understand it the first time they heard it.

In the case of Ruth Crawford Seeger’s Rissolty Rossolty it was more a matter of blink and you might miss it.

This miniature orchestral barn-dance by one of the 20th century’s more interesting composers is a delightful piece and, with conductor Finnegan Downie Dear’s explanation in between, merited a second hearing.

Steven Osborne was the soloist in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4, surely one of if not the greatest classical concerto.

It has sublime lyrical moments which Osborne captured beautifully, but what was most striking about his performance was the balance between the lyrical impulse and the vigour and energy that drives the music forward.

Few performers manage to find that balance as convincingly as Osborne.

A winner of the 2020 Mahler Prize, Finnegan Downie Dear is well-qualified to direct Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Part pastoral idyll, part heavenly vision, and part nightmare, its discursive length can easily lead a performance to flounder.

Downie Dear maintained a tight rein over it, while still allowing it to breathe. The orchestra responded to his direction with enthusiasm and passion, resulting in some of the best playing that the ASO has produced this season.

Stephen Whittington

Home, I’m Darling – Therry Theatre

Arts Theatre

August 17-26

Therry Theatre takes a plunge into fairly edgy theatre in its spritely production of Home, I’m Darling, an Olivier Award-winning piece by English playwright Laura Wade.

It’s a curious piece, to be sure, about a married couple, Judy and Johnny, whose home life is lived entirely in the 1950s.

Their shared interest in the era has been a constant throughout their shared lives, and when Judy takes a redundancy from her job in finance, she proposes, and Johnny agrees, that she live the life in its fullness.

So there she is, cooking Johnny’s breakfast, making his lunch, keeping the house spic and span, making sure the dinner is on and the cocktails ready – having changed into something appropriate, of course – and so it goes on.

It’s a jarring piece in the 21st century, when understanding what women want actually means something.

Alicia Zorkovic is terrific as Judy, swanning around in one gorgeous dress after another, living out a fantasy.

Her willing subjection to male authority grates, even in the fact of thoroughly sensible and none-too-subtle warnings from her mother Sylvia (Deborah Walsh), who was an activist herself back in the day and retains a spine of steel.

As husband Johnny, Stephen Bills does an excellent job of a really difficult role. He’s nowhere near as committed to this “experiment” as Judy, but goes along with it, even as the pressure of living what he clearly knows is a lie – the fiction that the man of the house needs to earn the money, supported by the dutiful wife – grows to breaking point.

Director Jude Hines has done a fine job, drawing tactile, committed performances from the leads and a mix of empathy and incredulity from the supporting characters. The design from Gary Anderson is a marvel, ’50s to the core, abstract wallpaper, formica table and all, while the costumes from Gilian Cordell and Sandy Faithful are sensational.

As external factors tear the charade apart, the tension builds nicely. Something has to give, though playwright Wade takes a little too long to get there. Several of the later scenes that soften the eventual blow are at best superfluous, and it neither needs nor necessarily deserves a happy ending.

But as Doris Day sang, Que sera, sera.

Peter Burdon

Disney’s Winnie the Pooh – The New Musical Stage Adaptation

Dunstan Playhouse

August 17-20

What’s not to like about Winnie the Pooh? Or Piglet, or Eeyore, or Tigger, or Rabbit? And what’s not to like about Disney’s forays into this fantasy world?

This 2021 production mines the filmic archive from the 1960s on, with music mostly by the Sherman Brothers – again, what’s not to like? – and terrific life-size puppetry.

The puppeteers are part of the action, and it’s a testament to the strength and popularity of the subject matter, and their skill, that their presence manners not a jot.

They become one with their characters.

Alex Joy is all cuddly and loveable as Pooh, of little brain and boundless love for his friends. Rebekah Head is terrific as Piglet, and Andrew McDougall steals the show with a splendidly lackadaisical Eeyore, and like many of the other performers, doubling and tripling with other characters.

A curious decision on the part of writer Jonathan Rockefeller is to limit the appearances of Christopher Robin – no puppet here, performed live by Jess Rider – to cameos at the beginning and end. Quite why is a mystery.

The music is tried and true, and the cast interact flawlessly with the prerecorded soundtrack. As well you might expect from Disney.

The merchandise counter was doing a roaring trade. Piglet was the hot seller.

Peter Burdon

Australian Chamber Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

August 15

Nationalism as a political phenomenon has some negative connotations.

But the rise of national consciousness and cultural identity in 19th century Europe gave rise to some great music from many composers, including the Czech Antonín Dvorak and the Hungarian Béla Bartók.

They provided the major works in this exhilarating program from the Australian Chamber Orchestra.

The works have an affinity that goes beyond a certain nationalist inclination. They each have five movements that follow a very similar pattern. But when it comes to content they are sharply different.

Bartók’s String Quartet No. 5 is hard-edged modernism with rugged melodic lines and muscular, asymmetric rhythms.

I have sometimes taken the ACO to task for adapting string quartets for chamber orchestra on the grounds that it destroys the fundamental intimacy of the music.

But I have to admit that this performance was a triumph of collective virtuosity that only a chamber orchestra of the calibre of the ACO could bring off – and possibly there is no other orchestra who could do it.

Dvorak’s Serenade for Strings is one of the most-loved works for chamber orchestra, and how could anyone not love it?

Lushly romantic, with haunting themes and beautifully conceived for strings, it ticks all the boxes required for enduring popularity. The ACO obviously loved playing it, and that feeling enhanced the pleasure of listening to it. And of course they played it superbly.

New York-based Caroline Shaw is definitely have a moment, with her works popping up everywhere. Her Entr’acte features some intriguing effects woven together into a rather intricate tapestry of sounds.

The somewhat underrated Czech composer Josef Suk’s Meditation is a lovely work from which the ACO produced a continuous flow of beautiful orchestral textures.

Stephen Whittington

Kissing the Witch

University of Adelaide Theatre Guild

Little Theatre

August 10-20

The plays of Irish-Canadian writer Emma Donoghue are largely overshadowed by her novels, more’s the pity, though her current celebrity as writer of the Netflix hit The Wonder has recently propelled her well above the radar.

So good on the Theatre Guild for giving a rare performance of Donogue’s Kissing the Witch from 2000, an adaptation of some of the pieces from her 1997 novel of the same name.

Each of these are “fractured fairy tales”, drawing freely on the classics – from the Brothers Grimm to the Little Mermaid – and twisting them more or less subtly.

The twist is that the stories are told from the female perspective, with the lightest yet most incisive of touches.

Three women tell the tales, exchanging the role of the ever-present witch who weaves in and out of the five stories with the other fanciful characters.

Their triumphs and tragedies become much more than the luck or folly of a stereotypical sweet or innocent or just plain silly girl.

The trio that bring the story to life are Susan Cilento, Ellie-May Enright and Michelle Hravtin. There are some excellent characterisations, and they accommodate the sometimes uneven writing, when Donoghue’s often evocative language veers towards the heavy-handed (That’s praise, not criticism).

Director Imogen Deller-Evans does a fair job in her directorial debut, ably assisted by an experienced team that includes Stephen Dean (lighting) and Thomas Brogden (set).

Donoghue’s long list of works is always gendered, often with a queer subtext, and Kissing the Witch is no exception.

The ever-present theme of awakening desire, often with the help of a female character, is surprisingly disruptive.

The performance reviewed was in-season, opening night nerves long past, and the reception from a full house was very encouraging.

Peter Burdon

Yuldea – Bangarra Dance Theatre

Her Majesty’s Theatre

August 10-12

“I am looking back to what has happened to our beautiful land of Maralinga, a land that was exterminated by the atomic bomb.”

So wrote – and, on this very special night, read out loud – senior Aṉangu woman Mima Smart, born in the year of the first of the British nuclear tests that were to blight the land over the next seven years.

The people of those lands were scattered. Mima went to Ooldea, on the edge of the Nullabor Plain, and lived for many years at the mission there. Later still, they were again moved, to Yalata.

This tragic story underpins the first new work for Bangarra under artistic director Frances Rings. It continues Rings’ abiding interest in place. It also shares her keen eye for structure and form.

The stage is dominated by a vast apsidal curtain made of countless strands of rope, the upper edge defined by a huge semicircular beam.

Into this space, designed by Elizabeth Gadsby, with flashes of light from all quarters, enter the dancers in a celebration of the night sky, one of the many references to Aṉangu custom and culture that flow throughout the work.

The majority of the work is given over to the finding of the Yuldea Kapi pit, the only source of water in the region, and the disastrous impact of colonisation and, later, forced removal. The second act, Kapi, is classic Rings, with wonderful colours and costumes – by long-term costuming and lighting collaborators Jennifer Irwin and Karen Norris – referencing the mysterious beauty of water and its vital role.

The birds and beasts know where the water is to be found, the birds with their blue plumage, the dingoes with their rusty coats.

Act three, Empire, references the arrival of the railway, an early bit of “nation building” which quickly drained the soak, and so a first forced removal.

An echo of an old hymn references their time at Ooldea, and life seems calm, if unfamiliar, until they are moved again, wrenched away from the desert.

The solo set depicting the fallout from the first of the Maralinga bombs is crushing in its impact, a figure writhing in agony, skin peeling, the poisonous rain and mist enveloping the land.

But ultimately, the ties that bind remain strong, and the last act, Ooldea Spirit is all celebration, a soft rock song tracing a Songline for the 21st century.

It was the last of a rich and diverse sonic story from composers Electric Fields.

The opening night was made the more exciting for the presence of a huge crowd of the Yalata mob, making the 12-hour journey to Adelaide to show their support.

Their sobs told of the terrible distress that remains 70 years on, while their cheers showed that they are still ready to party.

As well they might, for Yuldea is a triumph.

Peter Burdon

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Elder Hall

August 9

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra principal clarinet Dean Newcomb was unfazed to be standing in the shoes of legendary jazz clarinetist Benny Goodman, for whom Aaron Copland wrote his Clarinet Concerto in 1948.

In fact, Newcomb fashioned the solo part very much in his own personal style, one that audiences have come to greatly admire since he joined the ASO in 2008.

The work is glitzy and effervescent with touches of jazz and of South America where some of it was composed. Newcomb’s polished, finessed sounds, soaring effortlessly over the orchestra gave it added sophistication and polish.

After the sultry, reminiscent first movement, Newcomb’s clarinet acrobatics began to emerge during the cadenza middle movement leading into the vividly coloured, syncopated but oh-so-civilised last movement. Here Newcomb almost literally breezed along effortlessly bringing engaging sparkle and elegance at every turn.

Guest conductor Luke Dollman knows Elder Hall very well and it showed in the ASO’s neat, tidy and excellently crafted performance of Schubert’s 3rd Symphony, a youthful composition suffused with latent energy and high spirits. Dollman exuded a quiet presence that belied the fine results he achieved.

There was plenty of vigour and clarity in the exposed part writing of the opening Allegro with the ASO’s disciplined and rhythmic drive present in spades, although always beautifully balanced and suited to the hall.

The delicate Allegretto and wholesomely folksy Menuetto received similar treatment with the headlong rush of the final Tarantella as controlled and focused as you could possibly wish for.

Rodney Smith

Jeonghwan Kim, piano

Elder Hall

August 4

The spectacular success of K-Pop as a global phenomenon has drawn attention to South Korea as a musical powerhouse.

There’s a lot more to it than K-Pop. In recent years Korean classical musicians have been conquering the world in prestigious musical competitions. Their most recent success was at the Sydney International Piano Competition where Jeonghwan Kim took the first prize.

His win was thoroughly deserved, as anyone who heard his superb performances of concertos by Mozart and Bartok in the final round will surely agree.

Part of the prize is an Australia-wide concert tour, which brought him to Adelaide under the auspices of the splendid Harris International Piano Series.

His program was diverse, beginning with Beethoven and ending with Messiaen. From the extreme delicacy and refinement of Chopin’s Berceuse to the relentless, steely power of Prokoviev’s Piano Sonata No. 6, Kim displayed both boundless energy and admirable sonic imagination.

Whatever difficulties were confronting him – and they were immense – he appeared to be not merely unintimidated but relishing the challenges. Perhaps it’s his youth: He actually appeared to be enjoying himself on stage. His use of fist and elbow in the Prokofiev revealed a sense of fun that is rare in this context.

It’s difficult to pick a highlight from this dazzling display of pianism, but it was perhaps the Messiaen, which combined huge range of colours with remarkable technical fluency.

Encores by Ligeti and Chopin confirmed the impression that Jeonghwan Kim is major talent from whom we should hope and expect to hear much more.

Stephen Whittington

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and ANAM Musicians

UKARIA Cultural Centre

July 29

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra is one of the world’s oldest orchestras, and this weekend’s concert series at UKARIA celebrated its important role in European musical culture.

Musicians from the orchestra were joined by students from the Australian National Academy of Music in a program of chamber works of varied instrumentation.

The program was curated by Australian-born Gewandhaus Orchestra violist Tahlia Petrosian, and each work on the program was connected to the orchestra’s long history.

The Saturday afternoon concert featured music by J.S. Bach, Mozart, and Richard Strauss.

Bach’s Ricercar a 6 from The Musical Offering, transcribed for string sextet, was played with beautifully pure tone and subtle shading that worked well in this venue. Mozart’s Serenade in C minor for Winds followed. The final movement was particularly compelling, with lively articulation and effective contrasts between each variation. Strauss’s Metamorphosen, reduced from its original 23-player version to a septet, was still rich in timbre.

Saturday night’s performance included Felix Mendelssohn’s Piano Sextet in D and Dvorak’s Serenade for Wind Instruments, Cello And Double Bass. The unusual instrumentation of the Dvorak was inspired by Mozart’s Serenade from the previous concert. But the addition of an extra horn, contrabassoon and low strings gives the piece much more satisfying balance and an expanded colour palette.

The piano sextet was a highlight of the program, with stunning playing from the strings in the solo movement, and wonderfully detailed phrasing from pianist Reuben Johnson.

Melanie Walters

Vitality – Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Pinchas Zukerman, conductor and soloist

Adelaide Town Hall

July 28-29

Violinist Pinchas Zukerman has been at the top of his profession for more than half a century.

In this concert he convincingly showed that he still has the qualities that propelled him to the pinnacle of the classical musical world.

Like many others, he has chosen to add conducting to his portfolio, often conducting while playing at the same time – a combination more common in Baroque music.

In the first half of this concert though he was only conducting, with an unusual assortment of pieces.

First was Starburst by Jessie Montgomery. It’s a short, muscular work effectively interweaving voices and asymmetric rhythms in an idiom which is representative of one strand of contemporary music currently emanating from the United States.

Ballade by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, composer who rarely appears on the concert platform here, came next. In a late Romantic idiom, it’s competently written though veering towards bombast and sentimentality at times. He died tragically young and may have gone on to greater things.

The first half concluded with the overture to La Forza del Destino by Verdi, a fine performance that captured both the lyrical and dramatic sides of this piece.

After interval Zukerman came on stage with his violin, but maintained the role of conductor by turning to the orchestra and waving his bow when he wasn’t playing.

This combination of roles doesn’t always work but, overall, it did on this occasion. He has no doubt performed Beethoven’s Violin Concerto on countless occasions and knows exactly what he wants to do with it.

There were no revelations, but there was plenty to admire in listening to a performance by someone who knows this wonderful work inside out.

Stephen Whittington

Shifting Perspectives – Restless Dance

Queens Theatre

July 27-30

In just a couple of years, Illuminate Adelaide has established itself as a serious contender on the national festival scene with its spectacular light-driven events all over the city.

Raincoats and puffer jackets reign supreme as thousands brave the elements to delight in the installations all over the city.

Inside the theatres, too, there are joys to behold.

In 2023 Illuminate has commissioned Restless Dance to present Shifting Perspectives, a nice play on words in that perspective not only relates to representations of height and depth and position, but also to ways of regarding something – or someone.

The audience gathers inside the door of the cavernous Queen’s Theatre – there is plentiful and effective heating – and all don white gloves, gently fluorescing under a gentle blue light.

Mirrored towers intrigue and attract, members of the crowd seeing themselves and others, and in reflection, ghostly projections of the dancers high above the entrance, moving in slow motion.

“Roam, shift, drift,” says a beguiling, calming voice. “Touch the mirror. Gaze at your reflection.”

As the minutes tick by, anxiety about the enforced participation seeps away, and we become immersed in the spectacle. There’s no hesitation when we’re encouraged to join hands, a dozen or so processions snaking into the main performance space, where a breathtaking forest of the same mirrored towers awaits.

The idea is simplicity itself, mere uprights on a stage. But with the mirrors, and the brilliant lighting design from light artist Matthew Adey, it takes on an uncanny depth and complexity.

Restless artistic director Michelle Ryan weaves the dancers in and out of the space, the occasional flashes of light bringing interest and excitement to the movement.

The audience is encouraged to move about to look from a different angle – and please, do it – to experience the dance and the dancers in different ways – perspectives, remember – as they weave in and out of view.

Sascha Budimski’s sound design both supports and propels the movement, never more so than towards the end when a techno beat and laser light underpins a sequence where the Restless dancers do what they do best, which is revel and rejoice, and bring the audience along for the ride.

Their infectious enthusiasm never fails to delight.

Peter Burdon

Chopin’s Piano – Musica Viva

Adelaide Town Hall

July 26

Paul Kildea and Richard Pyros’ adaptation for stage of Kildea’s book Chopin’s Piano attempts two noble aims.

The first is to have all 24 Chopin Preludes performed live on stage, and the second is to present some of the story surrounding their completion in Majorca and the small piano Chopin used on the island.

The first aim was achieved very successfully with pianist turned actor Aura Go giving some superb accounts of these famous pieces scattered throughout the evening.

Her playing is unremittingly warm-hearted and insightful, with her deep rich tonal qualities bringing all Chopin’s pathos and delicacy into bold relief.

Her account of the C minor Prelude was especially memorable and captured wonderfully its elusively subtle simplicity.

The second aim was met with more mixed results. Actor Jennifer Vuletic was tasked with portraying eight different roles relating to figures involved in the piano’s chequered history, and brought big-scale dramatic flair and characterisation to them in bravura performances.

In passing it should be mentioned that Go had to assume the character of a further seven roles – a tour de force.

Nevertheless, there was inevitable blurring of the script and dramatic structure with only two actors involved, not to mention sometimes less-than-crystal-clear dialogue caused by the resonance of what is essentially a concert hall rather than a theatre.

The result was an evening of highs and lows, but there’s no denying Vuletic’s war-torn Wanda Landowska stays in the mind.

Rodney Smith

Sjaella

Ukaria

July 16

From the moment it began there was something magical about this concert.

The six singers emerged from different directions, and there was much cheeping, chirping and chirruping.

It was a vocal version of A Bird’s Prelude from Henry Purcell’s “semi-opera” The Fairy Queen.

This being about fairies and other supernatural beings, magic was definitely in the air, but the real magic came from Sjaella, an a capella group of six young women from Leipzig whose beautifully blended voices and engaging manner held the audience spellbound throughout the concert.

It was far from an ordinary program. Apart from welcome chunks of Purcell, the first half had contemporary works by New Yorker Caroline Shaw, who is clearly having a moment right now, and Ina Meredi Arakelian, known professionally simply as Meredi, a Berlin-based composer whose piece Crystallized made ingenious use of variety of vocal sounds and noises in a fascinating piece that was reminiscent of Meredith Monk.

Most unusual of all though was Hypophysis, a joint compositional effort by the group itself, and perhaps the only a capella choral work about the menstrual cycle, treated in this case in a lighthearted way.

After interval Sjaella presented a series of folk-song arrangements mostly from Northern Europe, in which the supernatural featured again along with more earthy sentiments.

There were no moments of high drama in this performance; it proceeded in a calm and measured way as they drew the audience in rather than overwhelming it with histrionics. Throughout the concert Sjaella radiated a special kind of warmth, totally unaffected – they clearly love what they do, and that love was willingly reciprocated by their audience.

Stephen Whittington

Creation: Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Grainger Studio

July 14

Creation, by Bundjalung musician Grayson Rotumah, weaves together elements of storytelling, indigenous music, hip-hop, electronic music, and orchestral sounds.

Described as a concerto grosso, this work was part of the ASO’s Floods of Fire project and opens with the Yugambeh creation story of the Three Brothers.

The soloists – Rotumah on guitar and vocals, Robert Taylor on yidaki, Rulla Kelly-Mansell and Corey Theatre on vocals, and Dylan Crismani on electric crystal – were seated around a campfire, which gave the performance an intimate quality.

The electric crystal, which Crismani built as well as performed on, produces sound through wet glass rods, steel bolts and contact microphones. It might seem like the odd instrument out in this ensemble, but its ethereal, sustained tones set the atmosphere beautifully and blended well with both the orchestra and the yidaki.

The spoken word and vocals incorporated both English and Yugambeh, although the use of the latter was quite limited. It might have been more evocative to have more extensive use of the Yugambeh language. All the soloists gave compelling performances, and Rotumah’s short guitar solos were a highlight of the concert.

The orchestration, by local composers Luke Harrald and Connor Fogarty, worked best in the sparser, chamber music-like moments. There was some effective use of motifs from the percussion and woodwind sections, but there was scope for a broader palette of orchestral colours in a narrative work like this.

The narrative and musical concepts underpinning Creation are compelling, but there is room to further develop this project into a more cohesive and expansive musical work.

Melanie Walters

Li-Wei Qin and Kristian Chong

Ukaria Cultural Centre

July 9

Cellist Li-Wei Qin and pianist Kristian Chong are a perfect musical match. Like-minded with all-encompassing techniques and definite ideas about how romantic music should sound, their program was a real charmer.

Bookended by Mendelssohn and Chopin Sonatas with smaller occasional pieces in between there was plenty for their audience to enthuse about.

Mendelssohn’s Sonata for Cello and Piano No 2 in D Op 58 is one of his best works and is no lightweight. Its four-movement canvass provides an object lesson in formal control with contrasted moods always part of a bigger picture.

Qin and Chong embraced its polish and perspective wholeheartedly with Qin’s rich cello sonics and Chong’s always rhythmical, clear tonalities a perfect foil.

If listeners wondered about Ukaria’s new Steinway Model D, Chong’s handling of the Adagio movement’s opening procession of arpeggiated chords would have totally reassured them with the instrument’s marvellous depth and subtlety positively shining.

Qin showed equal prowess during the effervescent, driven first movement Allegro in a strongly projected reading.

Chopin’s even more expansive four-movement Sonata for Cello and Piano in G minor Op 65 closed the program and written but a few years later makes a fascinating comparison with the Mendelssohn.

Both Qin and Chong revelled in the trademark poetically discursive moments that Chopin happily intersperses with more dramatic and turbulent episodes throughout.

Despite their herculean efforts the music didn’t coalesce like the Mendelssohn, although it was a wild ride and relished by all.

Rodney Smith

Mary Poppins delivers spectacle

There’s only one word to describe the sheer magic that is Mary Poppins the musical, and that word begins with “Super” – which this show is from go to whoa.

Blending the best of the classic Disney film with some of the more serious (or delightfully mischievous) lessons to be learned from P.L. Travers’ books, it features one astounding visual spectacle and singalong tune after another.

You won’t just believe a nanny can fly, you’ll actually witness it as Poppins and her umbrella literally ascend to the rafters.

The show opens like a children’s storybook, with the black-and-white illustrated backdrop of Cherry Tree Lane unfolding to reveal the colourful, multi-level rooms inside the Banks household, where yet another nanny has quit in frustration.

Out of nowhere, Poppins appears in answer to the children’s own advertisement, just the first of many sleight-of-hand tricks and clever props which put a modern spin on traditional stage magic to create wonderful illusions.

Hat stands and pot plants are produced from tiny bags, kitchens explode and reassemble, and even the icing on the cake has a life of its own.

A walk in the park erupts with Technicolour blooms and dancing statues, kites stream across bright blue skies and a rollicking rendition of that aforementioned song is accompanied by its own choreographed sign language.

Stefanie Jones is, as her theme song says, Practically Perfect in the title role, her constant poise and pert precision executed like the moves of a clockwork ballerina.

As jack-of-all-trades Bert, Jack Chambers is a perfect comic foil.

His own dance moves swing from the hilarious to the breathtaking, especially as he leads the chimney sweep ensemble through an exhausting tap routine on Step In Time and defies gravity by dancing on the ceiling. Move over, Lionel Richie.

Patti Newton is given a rousing reception for her truly moving cameo as the Bird Woman, her voice as pure, sweet and strong as ever.

It’s the story of mending a fractured family, and seeing beyond facades to find the true value within. But most of all, it’s Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.

Mary Poppins is at the Festival Theatre in Adelaide until August 27. Book at marypoppinsmusical.com.au

Embrace: Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Adelaide Town Hall

July 7 and 8

The title Dare to Declare beautifully set the tone for Anne Cawrse’s new marimba concerto.

The concerto, which was given its premiere on Friday by Claire Edwardes and the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, takes its title from a line poem by British poet Nicola Slee.

It is in three movements, each inspired by a formidably-talented Australian artist.

In Oodgeroo, wordless settings of poetry by Oodgeroo Noonuccal were woven into atmospheric textures.

The marimba is not an instrument traditionally associated with lyricism, but Edwardes’s playing was incredibly lyrical and expressive, with nuanced phrasing and impeccable balance.

Cawrse’s writing employed the full range of the instrument to great effect.

The second movement, Clarice, was inspired by the misty landscape paintings of Clarice Beckett.

As with the previous movement, Clarice featured a beautiful palette of orchestral colours and the soloist imbued every note with pathos.

Peggy Glanville-Hicks was a powerhouse in Australian music. Peggy, the final movement of the concerto, really captured the vitality of the composer, with vibrant, irregular dance rhythms. Edwardes conveyed this energy with both technical flair and elan.

Dare to Declare is a wonderful addition to the niche repertoire of marimba concertos, and deserves many more performances.

The preceding work on the program, Kodaly’s Dances of Galanta, shared the vitality of the final movement of the concerto.

Elena Schwarz’s precise and energetic conducting style brought out a great variety of articulation and character from the orchestra.

Rounding out the program was Dvorak’s ever-popular ninth symphony.

Melanie Walters