Gauguin’s World: National Gallery of Australia exhibition examines complex artist

Vincent van Gogh sliced off part of his ear after quarrelling with Paul Gauguin – but the artists’ complex friendship inspired one of the standout works in a new Australian exhibition. WATCH THE VIDEO

Arts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Arts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Paul Gauguin created some of the most beautiful art the world has ever known. But the myth that surrounds his life has equally become his legacy.

It goes like this. Gauguin was born in 1848, became a Parisian stockbroker, took up painting in his 20s, ditched his job, abandoned his wife and young children, and voyaged to the Pacific Islands in his 40s in search of hedonism and free love.

The kernel of the myth is true.

But, in a major new exhibition which opens in Canberra on June 29, the National Gallery of Australia has taken an updated, 21st-century look at the Gauguin story – seedy parts and all.

The exhibition is titled Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao, which translates roughly as Gauguin’s “world and essence”.

Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao is not a packaged exhibition that touches down on a multi-stop world tour. It was conceived and curated especially for the NGA by Henri Loyrette, a former director of the most visited museum in the world – the Louvre in Paris.

Loyrette worked on the exhibition with the NGA, the organising body Art Exhibitions Australia, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. MFA Houston will be the only other venue to host the show after it closes in Canberra in October.

The exhibition boasts more than 130 works of art, traversing painting, drawing, engraving, sculpture and decorative art. Lenders include the Musee d’Orsay in Paris, and museums and private collections in the UK, Japan, Brazil, Tahiti and Abu Dhabi.

Expect to see some Gauguin masterpieces that may never come to Australia again.

Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao is the world’s first Gauguin retrospective in 30 years, according to NGA director Nick Mitzevich.

It presents works from across Gauguin’s entire career in art, from his earliest full-scale painting in 1873 to his sojourns to Brittany and to Arles (where Vincent van Gogh sliced off part of his ear after quarrelling with Gauguin) and to Martinique.

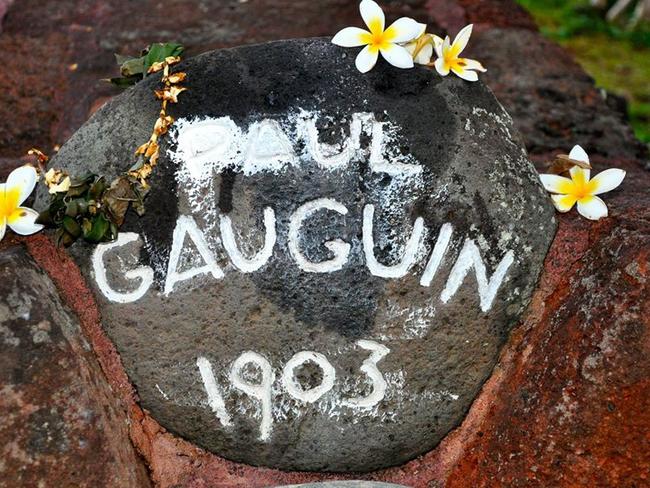

But the enigmatic portraits and richly coloured landscapes of the artist’s final years in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands are sure to be the high point of the show. Gauguin died in the tiny town of Atuona on the Marquesan island of Hiva Oa in 1903, aged 54.

It’s a special exhibition from many angles.

“This is the first exhibition devoted to Gauguin and Oceania: a survey of his entire corpus as seen from his final destination, the Marquesas,” Loyrette says.

Gauguin’s stunning Pacific paintings are famous for their colour harmonies, in which Loyrette believes the artist was attempting to make us smell, taste and hear the islands as well as see them.

While curating the show, Loyrette travelled to the islands where Gauguin lived from 1891 to 1893 and then from 1895 until his death; in between, he returned to Europe.

In Atuona, Loyrette stood inside a recreation of the hut Gauguin built. The artist called it Maison du Jouir (House of Pleasure).

Loyrette was pleased to see how undeveloped the islands were: “When you go to the Marquesas, it’s very striking. It’s marvellous, because it’s untouched. You hear the sounds, you hear the voices, you smell the perfumes and you see the landscape, and you understand a lot about (Gauguin’s art).”

Loyrette refutes the myth that Gauguin completely abandoned Western culture in the islands. On the contrary, he kept up a frenzy of correspondence with friends and supporters in Paris and had many questions. What were people saying about his work? Were his proxies working hard to promote his work?

No matter that he was thousands of kilometres from Paris, Gauguin kept his artistic pantheon to hand. He decorated Maison du Jouir with photographs of work by his great friend and supporter Edgar Degas. He also had images of work by Edouard Manet, Auguste Rodin, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Hans Holbein, among others.

“Gauguin organised a kind of little museum in his house, and I think that’s very moving,” Loyrette says.

Contradicting the myth that Gauguin immersed himself in a halcyon island paradise to the exclusion of all else, his letters home betray his occasional loneliness, and his poverty and ill health. He died alone in the Maison du Jouir while friends went to fetch medications.

So how did the full Gauguin myth develop?

Gauguin did a fair bit of self-mythologising, being quite the narcissist. But English writer Somerset Maugham’s 1919 novel, The Moon and Sixpence, was based on Gauguin’s life. It enlarged the myth and spread it widely.

The Parisian poet and art critic Charles Morice did his bit too, according to Australian-born anthropology professor at Cambridge University Nicholas Thomas, whose book, Gauguin and Polynesia, has just been published.

Thomas says Morice energetically promoted the image of his friend Gauguin as a swashbuckling iconoclast.

“Morice was obviously completely captivated by Gauguin and makes himself into Gauguin’s agent,” Thomas says. “Morice generates that notoriety, very much about Gauguin disappearing into this ‘primitive, savage realm’.”

But Thomas believes this ignores Gauguin’s attempts to remain relevant back home.

“Gauguin engaged insistently with artists, friends, critics, dealers and prospective publishers back in Paris and elsewhere in Europe, to whom he sent letters, sketches, manuscripts, paintings and other works,” he writes in Gauguin and Polynesia.

“In one sense, Gauguin permanently removed himself; in another, through those communications and artefacts, he never left”.

It’s undeniable that Gauguin cohabited with very young women and at least one adolescent girl when he lived in French Polynesia, and this has tarnished the artist’s reputation in the 21st century.

But the NGA, through the exhibition and events, is seeking a deeper understanding of the artist’s last years in the Pacific Islands.

To do so, it has engaged with contemporary Pacific artists and scholars to look at how Gauguin and his lifestyle choices can be interpreted today.

“We’re of the view that art needs to open up dialogue rather than close it down,” Mitzevich says.

“We’re not interested in cancelling anything. We’re interested in using art to open up the discussion about the world we’re in now and the world which we’ve inherited.”

Polynesian scholars have contributed essays to the exhibition catalogue, and spoke at a Gauguin symposium at the NGA on June 28.

They include Dr Vaiana Giraud, who is on the committee for the creation of the planned Espace Gauguin in Tahiti, and Polynesian artist, curator and architect Miriama Bono.

Despite challenges to parts of the Gauguin myth, no one will dispute the artist’s irascible nature. When he got to Tahiti and the Marquesas, it’s no surprise that he clashed with church and government authorities over their suppression of traditional island ways of life. He told parents, for example, that they could not be forced to send their children to school.

Gauguin had “immense respect for Indigenous cultures”, according to Gary Tinterow, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

“What has been particularly valuable for our (exhibition) catalogue is that we have contributions from Tahitian scholars and experts who have much better understanding than we do of what life and culture were in 19th century Tahiti,” Tinterow says.

“They’re helping us appreciate Gauguin’s art more completely in its contemporary context.”

Gauguin remains ubiquitous in contemporary French Polynesia. He’s on tea towels and mugs. Even a visiting cruise ship is named after him. But did Gauguin make the Pacific Islands, or did the Pacific make him?

For at least one contemporary Pacific artist, the answer is clear.

Francoise Schneiders titled her photographic work, F*ck you, I’m not your Dusky Maiden.

Schneiders’ piece will be shown in an exhibition running parallel to the main Gauguin show. It’s called SaVAge K’lub, Te Paepae Aora’i – Where the Gods Cannot be Fooled (until October 7 at the NGA).

Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao will show the broad range of the artist’s inspirations, from Peruvian and Egyptian culture to Japanese prints and French realism, Mitzevich says.

“We take you on the journey throughout his life and throughout his experiences, and we end with the Tahiti works,” Mitzevich says.

During his visit to Hiva Oa, Loyrette visited Gauguin’s grave overlooking the sea. For the scholar who has devoted years to this extraordinary artist, it was a moment to treasure.

Did he leave a stone or some other memento on the grave?

“No, no,” Loyrette says. “Our thoughts and prayers, but nothing else.”

GAUGUIN’S WORLD HIGHLIGHTS

According to National Gallery of Australia director Dr Nick Mitzevich

Femmes de Tahiti (Tahitian women) 1891

“Gauguin painted this work during his first months on the island. He takes the extraordinary light and colour of Moana/the Pacific to capture two Tahitian women resting between their daily tasks. This is a beautiful example of Gauguin’s use of bold outlines and sumptuous colour. His unique style had a profound impact on 20th century modern art, influencing artists such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.”

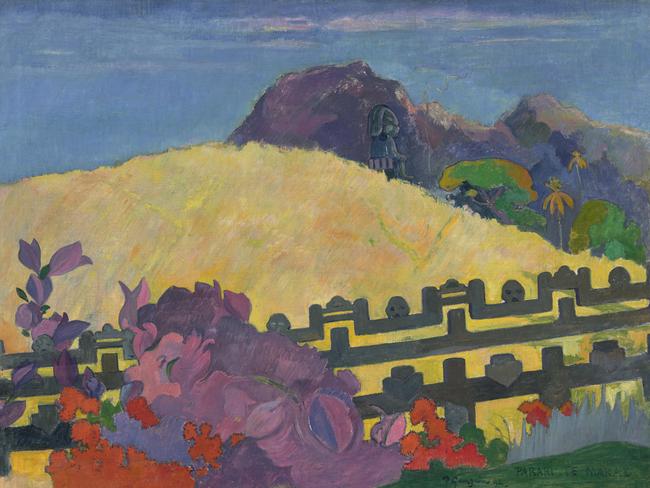

Parahi te marae (The sacred mountain) 1892

“Gauguin creates his own marae or sacred mountain, taking designs and motifs from other sources and putting them together into one extraordinary image. The fence in the foreground is based on the structure of Marquesan bone and shell ear ornaments, while the large stone statue in the background resembles mo‘ais of the distant Easter Islands.”

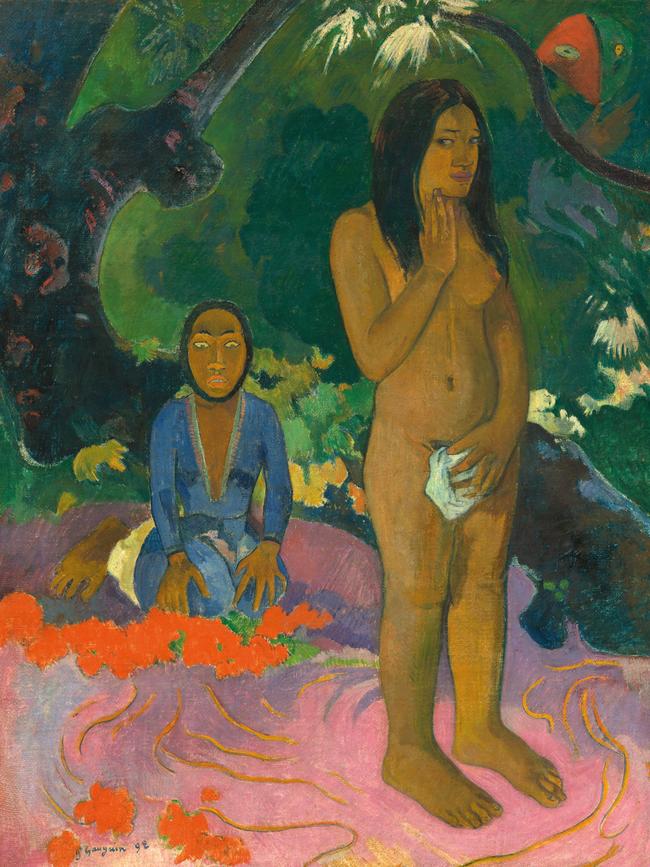

Parau na te varua ino (Words of the Devil) 1892

“Gauguin brings together Tahitian and Christian imagery to create a story that could be about Eve and the Garden of Eden – or, in this case, a tropical garden. The central figure is inspired by the biblical Eve or perhaps even Botticelli’s famous painting Birth of Venus. This is a great example of how Gauguin takes themes, stories and references from a wide range of sources to create an entirely original work. You’ll see images of a snake, a panther-like tree and a crouching, haunted-looking person, all of which come together in this beautiful and mysterious work.”

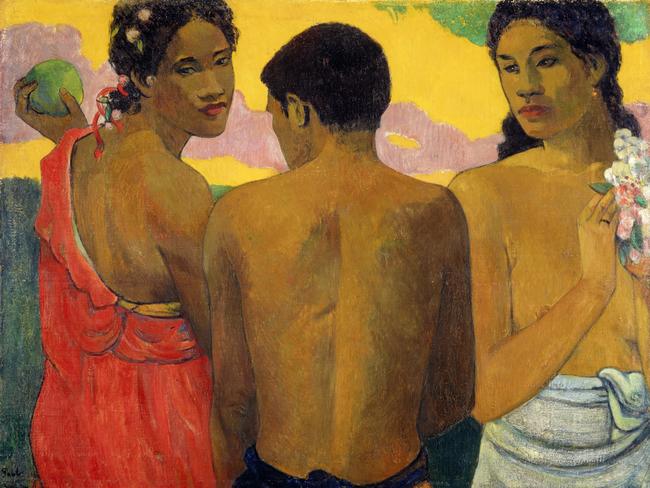

Trois Tahitiens (Three Tahitians) 1899

“The Three Tahitians is considered one of Gauguin’s most important paintings. He gives his colourful figures a real sense of solidity against an atmospheric background. There have been many interpretations of this work. Some think it is inspired by classical Greek mythology, others have focused on the unripe mango, the garland of flowers in hair of the women in red. You can see the woman on the right is wearing a wedding ring and holding a bouquet.”

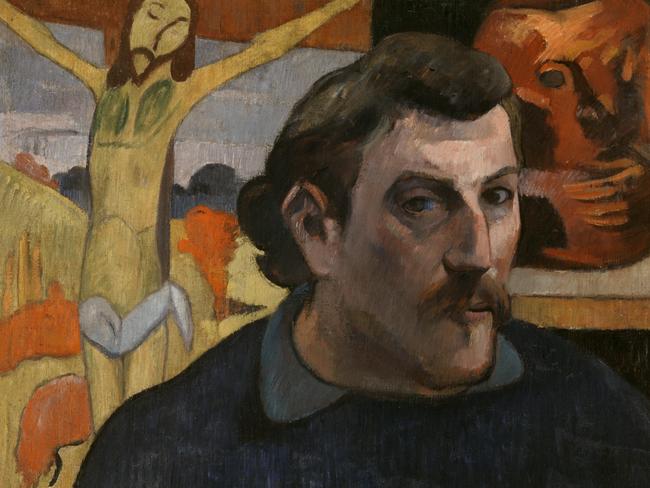

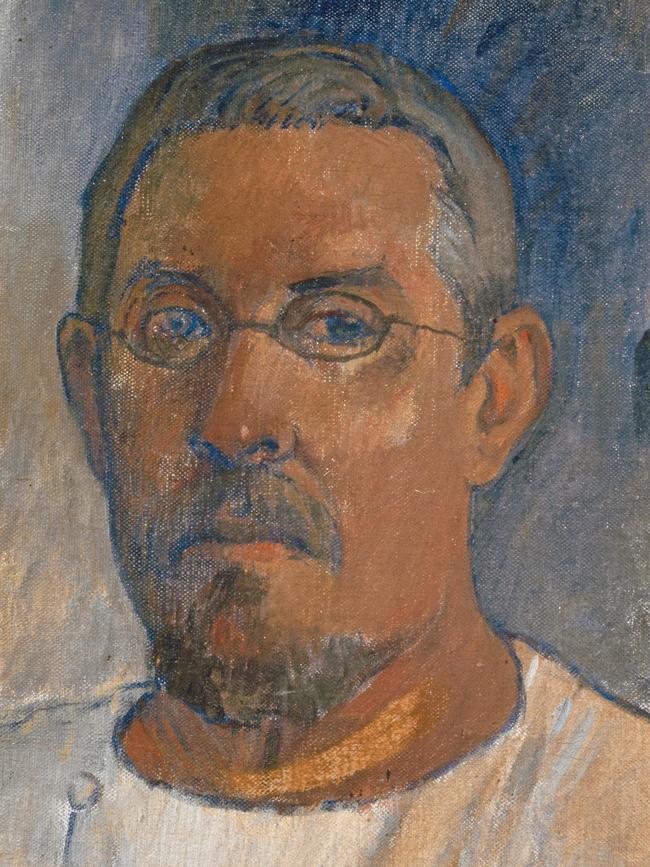

Portrait de l’artiste par lui-même (Portrait of the artist by himself) 1903

“This is the last self-portrait Gauguin completed before he died in May 1903. A very poignant and reflective work, you get the sense of a man who knows he is reaching the end of his journey. The painting is often compared to Egyptian mummy portraits, intended to safeguard the memory of the deceased.”

Still life with Hope (Nature morte a l’Espérance) 1901

The sunflowers in Still life with Hope is a tribute to Gauguin’s friend Vincent van Gogh, who had died a decade earlier. This exhibition offers a rare chance to see it in public, as it was purchased by a private collector from Milan in 2019.

Originally published as Gauguin’s World: National Gallery of Australia exhibition examines complex artist