SA Museum to expand World Mammals Gallery, starting with flamingo pair for Feast Festival

It’s a part of the Adelaide Museum that may be stuffy but, unlike its animals, it’s far from stuffed.

Education

Don't miss out on the headlines from Education. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It can be unnerving, yet completely fascinating, looking into the eyes of creatures that died decades ago as they stare back at you from behind the glass.

Then sometimes you can’t escape the feeling that those eyes are following you around the room.

Taxidermy displays are undeniably anachronistic, yet the one at the South Australian Museum still manages to spark the imaginations of visitors young and old.

Such exhibits are in the spotlight thanks to the New York Times reporting on the Melbourne Museum’s decision to dismantle its ageing display, citing insect damage along with the need to modernise the institution’s offerings to the public.

The international attention focused on a specimen known as Sad Otter, which due to its tatty state and downcast expression, had previously shot to fame a decade ago after it featured on the Bad Taxidermy website. The museum shop even sold a plush toy replica.

But here in South Australia, there are plans to rejuvenate and expand our museum’s World Mammals Gallery, after it survived previous attempts to remove most of it. Most of the gallery’s animals once lived at the Adelaide Zoo. When they died, their bodies were sent to the museum where they were preserved and mounted for the generations to come.

Among the more than 170 specimens – some of which died more than a century ago – there are nearly 60 from tropical Asia including a tiger, orang-utan and Indian elephant, and more than 50 African animals, with big attractions being a lion, hippo and leopard.

The Americas are well represented by a black bear, puma, tapir and armadillo, while Eurasian specimens include a polar bear, moose, wolf and beaver.

Generations of children have developed a fondness for what some call the “Dead Zoo” and its centrepiece, the lion with a twitching tail. The mechanism is so unreliable that is has become a game to wait minutes on end for it to move. Blink at the wrong time and you miss it.

The tradition of preservation continues today, as the bodies of two former zoo favourites, flamingoes Chile and Greater, are stored in the museum freezer, awaiting their resurrection.

The plan is to prepare their bodies for public display during the Feast Festival in November, as two pink flamingoes are the LGBTIQ+ festival’s icon. It was long assumed, incorrectly, that both Greater and Chile were males.

Greater, an African greater flamingo, originally came to the zoo from either Cairo or Hamburg – records are unclear – and was at least 83 when he died in 2014, having survived a violent attack by four teenagers six years earlier.

Chilean flamingo Chile was the last flamingo left in Australia due to a moratorium on importation.

She was in her 60s when she was euthanised in 2018, after struggling with arthritis and other problems.

Previously thought to be male as she had never laid eggs, her gender was confirmed at autopsy.

The job of preserving the birds is in the hands of SA Museum taxidermist and 3D design specialist Jo Bain, who was just a boy when the World Mammals Gallery opened in 1972, almost 50 years ago.

Before that, the taxidermy displays were more ad hoc.

Mr Bain worked alongside his predecessor, taxidermist Winston Head, for more than a decade after he joined the staff as a teenager in 1981.

He remembers Mr Head as quite a character who told him that in the late ’60s and early ’70s, he was unofficially banned from entering Adelaide Zoo.

“He had walked through the zoo pointing out animals that would fill gaps in the museum’s collection and then animals would die. It just spooked some of keepers so much they suggested he not come back,” Mr Bain said.

In the early days of the collection, animals were preserved using a chemical cocktail known as “arsenic soap”, which included mercury and other nasties.

Since then, they have also been repeatedly sprayed with pesticides to keep insects at bay.

As a result, museum staff have been warned to avoid entering the display cases without proper protective equipment, such as a full hazmat suit and breathing apparatus.

It’s not just the hair or skin of the animal but also the gravel and dust at their feet that worries the occupational health and safety officers.

Previous attempts to change the display have fallen by the wayside.

A public outcry put a stop to former museum director Professor Suzanne Miller’s 2009 plan to use the space for a new information centre.

“It was announced to the public and then she had bags of hate mail saying ‘We’re going to call for your dismissal’,” Mr Bain said.

The gallery takes up a large part of the ground floor, which is prime real estate for incoming directors wanting to make their mark.

Mr Bain is proud of the collection and sees great potential for a “global biodiversity” display complete with more birds and reptiles.

He has an anaconda in the freezer, rolled up like a truck tyre.

Though as yet unfunded, the modernised gallery would have “theatrical” lighting effects both in the exhibits and the walkways, and touch screens telling the stories of animals that came from the zoo, as well as the taxidermy process.

Mr Bain has pioneered techniques using synthetic resins and rubber to produce exact replicas for some body parts rather than making traditional biological mounts.

He plans to re-create the flamingoes’ heads and legs to preserve their unique character.

“Birds’ faces shrink and you lose all that detail,” he said.

“If I mould them I will get every crease and nuance.”

Donate to the SA Museum Flamingo Fund at community.samuseum.sa.gov.au/donate

TALES OF CREATURES GREAT AND SMALL

From behind the glass, many of the SA Museum exhibits have stories to tell, often quite gruesome.

Grison’s grisly end

The grison – a carnivorous mammal like a weasel, also known as the South American honey badger – suffered a terrible end in 1975 when it pestered a puma in the cage next door at Adelaide Zoo and had its “arm” ripped off, bleeding to death.

“We never got the arm because the big cat ate it, so if you look at him really carefully he’s only got three limbs. That’s why he’s next to a little rock,” SA Museum taxidermist Jo Bain says.

Siam’s hidden time capsule

Miss Siam was Adelaide Zoo’s first elephant, donated by Thomas Elder, president of the South Australian Zoological and Acclimatisation Society.

She arrived in January 1884, transferring from Melbourne after originally arriving from Thailand in 1881, and became a favourite with visitors as she gave children rides.

After her death, she became part of the museum‘s collection and was put on display in 1905. The skin is on display in the World Mammals Gallery, while the skeleton is downstairs in the Science Centre.

Beneath the skin is a metal and wooden framework packed with 40 bales (two tonnes) of fine hay. It is rumoured to also house a zinc envelope containing coins “as a bit of a time capsule”.

Change of stripes

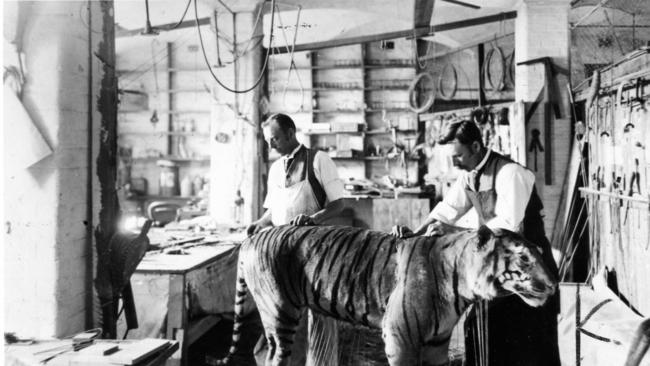

The Bengal tiger from India died in 1892 from natural causes. It’s fur faded to white with fawn stripes after many years on display under natural light, but was it painted by museum artist Madeline Boyce for the opening of the World Mammals Gallery in 1972.

Tale to give you chills

The polar bear died in 1920. It was shot after it tore an Adelaide Zoo keeper’s arm off, killing him.

Rhino’s real identity

The rhinoceros, which died in 1907, was originally believed to be an Indian rhino while living at the zoo. Museum scientists later realised it was a Javan rhino, the most threatened of the five rhino species.