Education report: Australian students stuck in the Dark Ages

Australian students are not equipped for 21st century learning with our schools struggling to prepare kids for life in the digital age.

Australian students are not equipped for 21st century learning with our school system still stuck in the dark ages as states and territories grapple with shifting to NAPLAN online.

With Australia’s education sector reeling from this week’s OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) report, showing Australian students are years behind the rest of the world in maths, reading and science, experts say we are widely unprepared for modern learning.

Australian education ministers agreed to push back the deadline for the NAPLAN online transition earlier this year to 2021 after the platform was plagued with technical issues but experts are calling for a complete review, saying there cannot be consistent data with so many states and territories at different stages of transition.

Despite the 2021 deadline, NSW and Victoria have refused to commit to a timeline for their full online roll out while WA say that 86 per cent of their schools will be participating in NAPLAN Online by 2020, Queensland say 860 of their 1700 schools will be involved by 2020 and Tasmania is already 100 per cent transitioned online.

The shift to NAPLAN online is also hamstrung by the deep inequity in terms of student access to devices and the lack of explicit goals for teaching touch typing in the Australian curriculum.

The PISA report observed that in the period since the last survey “the demands placed on the reading skills of 15-year-olds have fundamentally changed.

“The smartphone has transformed the ways in which people read and exchange information; and digitalisation has resulted in the emergence of new forms of text, ranging from the concise, to the lengthy and unwieldy.”

But in Australia there is a “digital divide” according to University of Western Australia’s Glenn Savage who says “kids are not on the same playing field when it comes to the day to day use of technology.

“Some schools are incredibly well resourced and others not at all. There are areas where it is difficult for parents to resource and schools can’t resource by themselves.”

St Therese Catholic Primary School in Sydney’s West has had an iPad program in place for three years and principal Michelle McKinnon said each student starts on the same playing field.

“We have really seen an increase in learning and attitudes. Our data is suggesting students are finding their learning more relevant and more purposeful and they are more interested,” she said.

“Our focus is on improving reading outcomes and the iPad is just one of the tools that we use to assist us. We have also seen an increase in attendance since the roll out and it has really lifted the expectations for learning – as well as the quality of work.”

Schools in Victoria and Queensland, which have run similar programs, have had comparable results.

Algester State School in Queensland reports a focus on digital teaching has seen a 41 per cent increase of students performing in the top two grades in English, 53 per cent now performing in the top two grades of maths and a 95 per cent increase in teacher feeling prepared for teaching with technology.

In Victoria, Melton Secondary College has provided a subsidy to assist all students purchase an iPad and their data has seen an increase in student engagement and attitudes to learning.

There has also been calls to ensure touch typing is better taught in schools.

With a number of touch typing courses now marketing themselves to parents to ‘get ready for NAPLAN Online’ experts are pointing to the lack of touch typing in the curriculum as being an issue.

Edalive Rohan Patterson, who runs a touch typing course that outsources to 2,000 schools across Australia, says curriculum requirements don’t require explicit teaching of touch typing.

“Almost every job we do in life requires us to be able to type and Australia needs to take more of a step in this direction like other countries do,” he said.

An ‘ACARA spokesperson’ said research has shown parents welcome the move to NAPLAN online and say” the NAPLAN paper writing test is not about handwriting skills and NAPLAN Online is not about keyboarding skills.”

But qualitative research method expert Dr Jessica Holloway, from Australian Research Council, Deakin University, said parents should be concerned about assurances that tests are comparable.

“We have to be careful in what we presume the tests can do. The typing point is very important because students might be using for keyboards for all sorts of things but they are not writing essays, they might be able to navigate technology but does that mean they can convey their ideas in the same way?”

Dr Fiona Mueller, Director of Education at The Centre for Independent Studies, said she also has concerns.

“Online assessment is one of the best examples of an issue that needs to be thought through with great care – actually the technological shift should be really straight forward in a country like Australia,” she said, adding that she also has concerns about the message it is sending around handwriting.

“Why would anyone continue to focus on handwriting? We stand to lose a lot.”

Why British kids are outperforming Aussies

British students’ maths results are improving after a change to the curriculum made the coursework harder and schools put an increased focus on the subject in primary schools.

As Australian students standards fall below where they were 20 years ago in New South Wales, six months behind where they were 15 years ago in Victoria and a decade of decline in Queensland, the UK has been bucking the trend.

The UK national curriculum was reviewed in 2014, with tougher standards and higher demands on students such as knowing their 12 times tables by the age of nine.

They also start learning fractions at the age of five or six, before some children in Australia have even started school.

The UK results from the international PISA test of 15 year olds showed that British students increased their maths results from 492 to 502 (out of a possible 550) and their English results from 498 to 504.

And that’s on the back of a trend of improving results since maths was put at the top of the class a generation ago.

Professor of Mathematics at University College London’s Institute of Education Jeremy Hodgen said that a greater emphasis on maths has been bearing fruit.

“The national curriculum was pared down and it changed from a levels based system to an aged-based system. And it had some more challenging things in it,” he said.

Prof Hodgen said it was too early to tell how the reforms had changed standards but he said there had been a generational shift in maths teaching in the UK, which began in 1995.

“We are starting to see our relatively high performance at primary mathematics show through into secondary,” he said.

“It might also be that the strong focus on mathematics from successive governments for the past two decades or so are starting to have an effect in secondary.”

Prof Hodgen said that some of the new generation of teachers had been part of the mathematics revolution and they were now better qualified to pass on their knowledge.

There remains a “serious shortage” of maths teachers in secondary schools, he added.

He said that the GCSE exam, which students take at around 16 years of age, had become harder and that was setting higher standards.

Students in the UK start school at four years old, compared with Australia where many children do not start until they are six years old.

Michael Gove, who was the UK’s Education Secretary at the time of the reforms in 2014, said the UK would no longer accept wasted human potential.

“People do still say we’re being and driving too hard,” he said when introducing the reforms.

“That is setting children up to fail and I will not tolerate that.”

Shock graph reveals where Aussie students are heading

By Clare Masters

Teaching standards need to be urgently boosted if Australia is to regain its position as a top education destination with new data showing we will slip to one of the worst in the developed world if nothing is done.

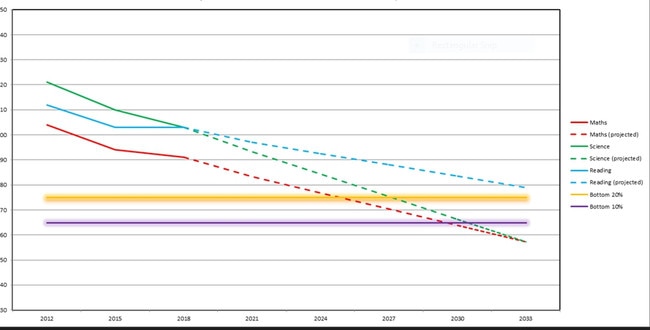

An analysis of international tests has shown that Australia’s performance in maths will be the fifth worst in the developed world by 2030 – down from fifth best in 2000.

In reading, Australia would drop to 23rd, from fourth in 2000 and in science we would slip to 31st from seventh, on the current trajectory.

Education leaders are now calling on teaching standards to be lifted, saying poor teaching is a large part of the problem.

It comes after the shocking results from yesterday’s OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) report revealed Australian students are years behind the rest of the world in maths, reading and science.

PROJECTED DECLINE IN AUSTRALIAN PISA RESULTS, 2012-2033

A projected decline, done by the federal opposition and confirmed by a Harvard-trained economist, examined the last three PISA tests and projects that Australia will sink to the bottom of the table of the developed countries if we do not reverse the slide. “It means Australia will have gone from one of the top performers to one of the worst,” Opposition spokeswoman Tanya Plibersek said.

Ms Plibersek blamed the current government for mishandling schools reform and Gonski funding roll out as initiated by Labor.

“We had a plan in place to turn the results around and then the Coalition turned their backs on that,” she said.

“What this analysis shows is if we continue doing what we are doing on this same path we are on track to have some of the worst results in the world.”

Ms Plibersek added that universities pack teaching students into courses because they are cheap to run.

“We can’t use teaching to subsidise other more expensive courses – we are cheapening the value of a teaching degree by lowering the standards,” she said. “We need to restore the status of teaching as a career and take our teachers from among our best and brightest.”

The last Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership report showed that in 2005, almost half of teaching entrants had an ATAR or equivalent of 80 or above but by 2016, that had fallen to one in three. While the Grattan Institute shows that the starting full-time salary for a teacher in most Australian states is between $65,000 and $70,000.

“Student outcomes will not start to change until the quality of teaching changes,” said Australian Catholic University’s Professor John Munro.

“Educators and policy makers have talked about the quality of teaching for at least two decades but don’t say what it looks like or how to do it. High quality teaching leads to high quality knowing and learning. School leaders often have difficulty recognising it.”

Australian Education Union Federal President Correna Haythorpe said flat salaries for teachers in most jurisdictions in Australia means there is no incentive to remain in the system.

Centre for Independent Studies, Glenn Fahey said the Australian system has “complete inflexibility” when it comes to paying teachers and there should be bonus and performance structures in place, as in the private sector.

Originally published as Education report: Australian students stuck in the Dark Ages