Falling UK COVID-19 transmission rates could hamper vaccine development

Falling COVID-19 transmission rates in the UK could hamper researchers’ ability to prove a vaccine works, while research on monkeys found the treatment didn’t stop them contracting the virus.

There is only a 50 per cent chance trials of the University of Oxford’s COVID-19 vaccine will succeed because slowing transmission of the virus in the UK could hamper research needed to prove it works.

And in another setback research on monkeys has found the jab does not stop them getting coronavirus.

Adrian Hill, director of Oxford’s Jenner Institute, told The Telegraph newspaper in Britain an upcoming trial in 10,000 people to test whether the vaccine stops people catching the virus could return a “no result” if community transmission of the virus continues to fall.

“It’s a race against the virus disappearing, and against time”, Hill told the British newspaper. “At the moment, there’s a 50 per cent chance that we get no result at all.”

In order to test whether the vaccine works researchers need to vaccinate a large group of people and compare the number of vaccinated people who get infected with COVID-19 with the number of people given a dummy vaccine.

If it works fewer vaccinated people would catch the virus.

In a statement on it’s website the University said “how quickly we reach the numbers required will depend on the levels of virus transmission in the community”.

“If transmission remains high, we may get enough data in a couple of months to see if the vaccine works, but if transmission levels drop, this could take up to 6 months,” the University said.

In a further worrying development research done at the National Institutes of Health has also raised doubts about whether the vaccine is even effective.

Six monkeys were given a single dose of the vaccine in the clinical trial and three were not given the vaccine.

The research has not yet been peer reviewed or published in a medical journal but a preprint publication in website biorixiv revealed all monkeys in the trial, both those given the vaccine and those who did not receive it, caught the virus.

“Viral gRNA was detected in nose swabs from all animals and no difference in viral load in nose swabs was found on any days between vaccinated and control animals,” the paper said.

However, the research indicated the vaccine might protect against the lung damage common in COVID-19 patients.

Another study in which rhesus monkeys were given a triple dose of the vaccine showed they too were protected from pneumonia caused by SARS- CoV-2.

The trial also appeared to ease fears that vaccination may provoke a worse form of COVID-19.

In 2003 animals given a trial vaccine against SARS developed a more severe form of the illness if they went on to catch the virus.

Billions of dollars are at stake if the vaccine does not work because pharmaceutical companies are already preparing to manufacture it even before clinical trials are complete to ensure it is ready to distribute if it is shown to work.

The UK has already ordered 100 million doses of the vaccine with 30 million doses to be available by September.

Meanwhile Chinese scientists have reported their vaccine produced antibodies to the coronavirus in early human trials.

Over 100 people were given the CanSino Biologics vaccine in mid- to late March.

There were three groups of 36 people in the trial and each group was given a different strength dose of the vaccine

Like the Oxford vaccine the CanSino Biologics product uses a modified adenovirus (which causes the common cold) to produce an immune system response to SARS-CoV-2 the virus that causes COVID-19.

The group reported in The Lancet medical journal that the vaccine produced neutralising antibodies to the virus which increased significantly at day 14, and peaked 28 days after the vaccination.

The vaccine also produced a response in immune system cells known as T-cells which peaked 14 days after vaccination.

The most common injection site adverse reaction was pain, reported by half (54%) of vaccine recipients.

Almost half those in the trial (46 per cent) reported fever, 44 per cent experienced fatigue, 39 per cent a headache and 17 per cent muscle pain.

“No serious adverse event was noted within 28 days post-vaccination,” the scientists reported.

This was a safety trial and further tests need to be done to see whether the vaccine stops people catching the virus in the community.

NEW TEST TO MEASURE EXPECTED SEVERITY OF COVID-19

Scientists are hopeful that a blood test will be able to show if people will become seriously ill with coronavirus.

The test may be able to help track a person’s immune response to COVID-19, allowing doctors to predict which patients may need more critical care.

The study found that people who got the most severely sick with COVID-19 had issues with a specific type of T-cell that clears the body of virus-infected cells.

Clinical trials will now be conducted to determine the efficacy of a drug called recombinant IL-7 (interleukin 7), which can increase a person’s number of T-cells, and in turn boost their immune response.

Analysing sixty coronavirus patients at St Thomas’ Hospital, researchers from the Francis Crick Institute, King’s College London and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust identified what they call the “immunological signature” of the disease.

“The changes we’ve observed in the blood are not subtle and patients with these features seem more likely to experience severe disease, requiring intensive management,” said project lead Adrian Hayday, who heads the Crick’s Immunosurveillance Laboratory and is professor of immunobiology at King’s College London.

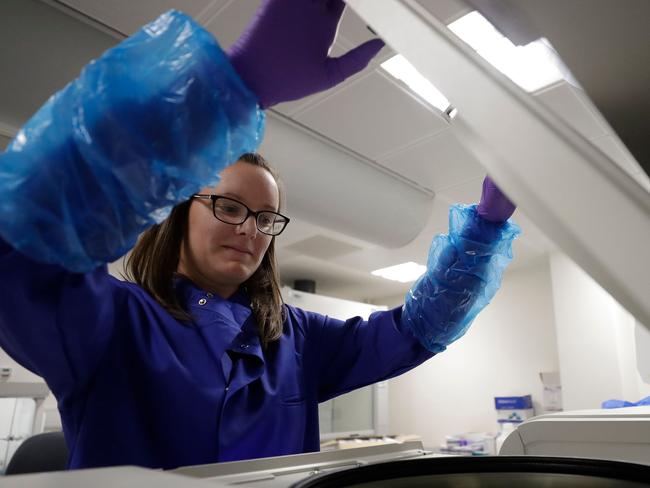

Their ongoing study, called COVID-IP, involves patients at Guy’s and St Thomas’ who have agreed to donate to an infectious disease biobank and provide regular blood samples during their treatment for the virus.

The samples are processed in secure containment at Guy’s Hospital before immune cells are analysed in the team’s laboratories at King’s College London and at the Crick.

The researchers hope such a blood test could be more broadly applied in hospitals to seek early indications of patient condition and to effectively help prioritise treatments.

Their findings may also be used to inform effective treatment and vaccine development.

Originally published as Falling UK COVID-19 transmission rates could hamper vaccine development