How SA Pathology is using genomic testing to track and trace every case connected to the Parafield cluster

We’ve been hearing a lot about genomic testing and super strains of a “sneaky” virus in Adelaide. So what’s it all about?

Coronavirus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Coronavirus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Anyone with more than a passing interest in the COVID-19 Parafield cluster is likely now familiar with the term “genomic testing”.

But what does it mean?

Scientists at SA Pathology have analysed the complete genetic sequence of the COVID-19 virus in every currently infected person in the state.

They have now connected every case in the cluster and traced the virus back to the source – a returned UK traveller in hotel quarantine at Peppers on Waymouth Street.

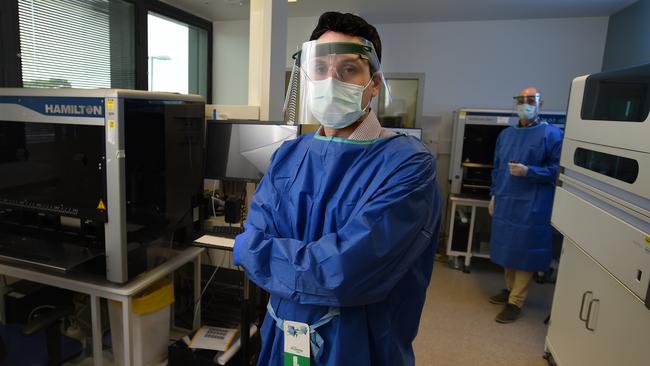

Clinical and laboratory virologist Chuan Kok Lim said he was alerted to every positive case of COVID-19 and initiated genome sequencing.

“When they’re positive, then we extract the viral nucleic acid from the swabs and then we go through a process of making a complementary DNA,” Dr Lim said.

“We amplify all these fragments into a large proportion, and then use these for the whole genome sequencing.

“So once we have generated a whole lot of small sequences, we map these sequences to what we call a reference viral genome.

“That’s the original Wuhan strain viral genome that’s been made public by China at the beginning of the outbreak.”

The whole process takes about two days. There is really only one “strain” of the virus SARS-CoV-2. It has not evolved or diverged sufficiently from the original to be considered a separate strain.

But there are many different variants on the family tree. Dr Lim said six “clades” – a group of organisms that had evolved from a common ancestor – of the virus, hundreds of lineages and probably even more sublineages had been identified.

Because the virus changes very slowly, at a rate of about two mutations a month, all cases in the Parafield cluster look the same.

It is impossible to tell, using genome sequencing, which was the first or subsequent generations.

That information comes from elsewhere, such as contact tracing, or even CCTV.

And you cannot work it out from when a person was diagnosed via a positive test, because the time taken from exposure to developing symptoms, or testing positive, varies from one person to another.

Dr Lim, also an infectious disease physician at the RAH, knows all the pieces of the puzzle are important. “It’s not a simple process,” he said.

Epidemiology professor Catherine Bennett, from Deakin University, in Victoria, has great sympathy for the SA authorities.

“They had a case where they thought someone had very casual exposure at the pizza shop,” Prof Bennett said.

“Normally, that would send alarm bells off that there’s something wrong here; you couldn’t just get it from picking up a pizza that someone in the backroom has cooked who might have the virus.

“But because they already had the cleaner story at the hotel at the start, it all was sort of fitting.

“But it was just slightly wrong information that actually gave them, I guess, a story that made them believe that the strain could be different. Then that made them more open to looking at these different modes of transmission than we normally see.”