Russia v China: One thing Putin and Xi both fear

Vladimir Putin rose to power through the KGB while Xi Jinping was born into privilege. But there’s one thing that terrifies these autocrats.

Leaders

Don't miss out on the headlines from Leaders. Followed categories will be added to My News.

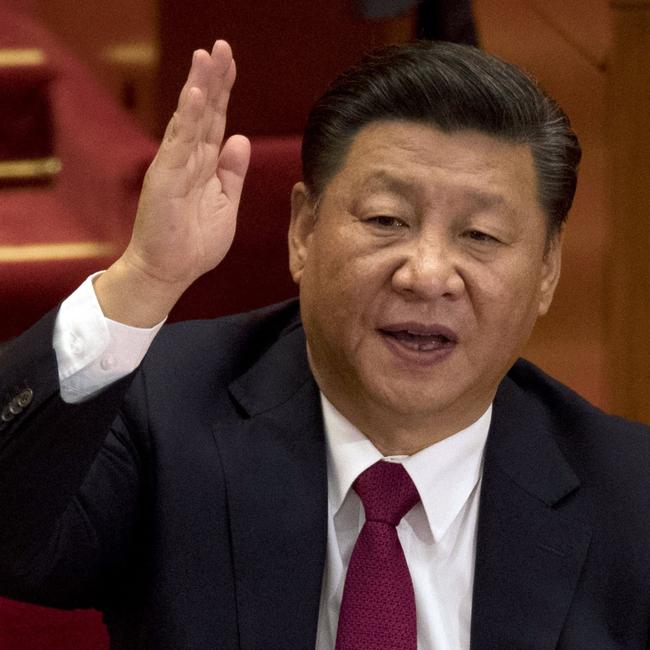

Vladimir Putin’s facing protests. But China’s “helmsman” Xi Jinping is going from strength to strength. So just how strong are the world’s two most prominent strong men?

Not all autocracies are created equal.

Most dictatorships live by the sword, and die by the sword.

But Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping appear to have learnt that lesson.

Putin rose to power based on connivance. He used his KGB training and connections to compromise and discredit all opposition.

Xi was a Communist Party princeling, born to privilege and peril. He built his empire on a network of loyalists within the framework of a single-party state.

Both have near-total control over all civil, military and legal branches of government.

Both are used to getting what they want.

Both are terrified others want to take this from them.

And that’s driving them together.

“Autocracy is a violent business,” says Yale University political scientist Dr Dan Mattingly.

“If you are an autocrat, who do you have to fear? What keeps you up at night?”

Coup.

RELATED: China and Russia’s aggressive master plan

Both Xi and Putin understand civil unrest is just the start. People power rarely topples dictators. “Instead, it’s coups,” Dr Mattingly says. “It’s other elites taking down elites. And that’s really what autocrats have to worry about.”

And the vast majority of successful coups are led by the military.

“So if you’re an autocrat, you really have to be nervous about what the military’s doing,” Mattingly says.

HOW STRONG IS STRONGMAN PUTIN?

RELATED: Russia on the brink of revolution

Putin’s KGB training has served him well.

With a small cohort of his former KGB intelligence officer colleagues in critical positions around him

Together, they form a new Russian nobility – free to manage and exploit their fiefdoms as they see fit.

“The keyword – we know it from the KGB handbooks used to train Putin, – is control. You control the populace,” says Australian National University visiting fellow Kyle Wilson.

“We know Putin is very fond of various sayings,” Wilson says. “One of his sayings, which he is very fond of, is “For my friends, everything. For my enemies, the law”.

While he and his supporters carefully control all television, one or two radio and print outlets remain outspoken. And there is no internet ‘Great Firewall’. Yet.

Why?

“There is a small section of the media which can be presented as genuinely representing an opposition,” Wilson says. “Putin can argue ‘we have pluralism in Russia, we have our variant of democracy, these people are allowed to express their views, we can put them aside, this is not China’.”

It’s worked well. Putin came to power in 2000. He’s poisoned, imprisoned, beaten and killed all serious opposition. Until now.

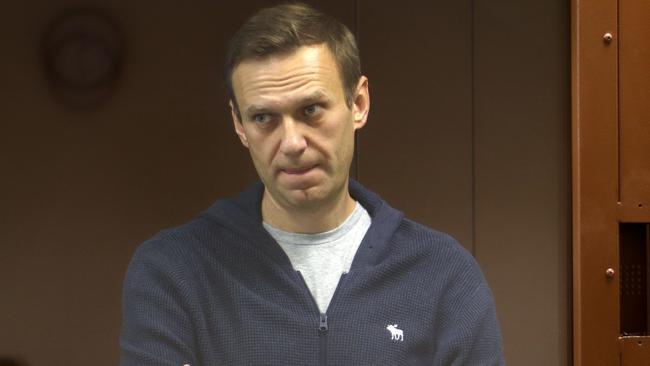

Anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny has become a Russian hero.

Putin tried to poison his underpants. He’s had him beaten. Jailed. Defamed.

Nothing appears to be working.

“Putin is failing to change,” Wilson says. “He has taken the decision clearly that he will use the nowt, that is the Russian whip, and the sabre to suppress this effort to reform the system. That is probably a fateful and potentially fatal decision for him because ultimately it will not work.”

HOW STRONG IS STRONGMAN XI?

RELATED: China’s brutal plan to become a superpower

Xi’s life as a Communist Party princeling has served him well.

As the son of a key revolutionary figure, he lived the privilege and power of Beijing’s ruling elite. He also survived the perils of its brutal power plays.

This gave him a thorough understanding of his nation’s strengths and weaknesses.

But the emperor-by-another-name faces a troubling precedent.

One in 10 of his imperial predecessors were toppled or killed by coups.

China’s population is strictly controlled through “grassroots” organisations such as neighbourhood committees and workplace associations. Everything is surveilled and recorded. All media – be it traditional or modern – is strictly controlled.

That same network has facilitated the construction of a personality cult.

Xi’s face is everywhere. Xi’s every utterance is broadcast. Xi Thought is compulsory reading.

But he’s not forgotten the military.

“In Xi Jinping’s speeches, he’s always talking about the triumvirate of the party, the state and the military,” Dr Mattingly says. “Clearly the military is on his mind.”

Before taking the top job, Xi secured the support of top generals and their military districts. But also the rank-and-file.

An analysis of military promotions over recent decades reveals most are ethnic Han. Most come from insignificant backgrounds. Most went to party-run schools and institutions. Many worked with Xi as he rose through the party ranks.

“Xi Jinping does appear to be quite conscious of who he’s promoting,” Mattingly says. “Between promoting people who are loyal to him, and promoting ‘left behind’ officers who aren’t well connected to other elites that he’s done enough to make it really hard to get the military to buy into a coup.”

RUSSIA DIVIDED

“One of Putin’s KGB bosses once wrote that ‘democracy takes from people everything a dictator has given them – a roof over their heads, food to eat, a job and stability – and offers them, in return, freedom’. And that very probably, is the view of Vladimir Putin,” says Mr Wilson.

Trouble is, it’s not true. And the experience of the average Russian is demonstrating this.

Then there’s Putin’s new nobility. It has the same issues as the old Tsarist regime.

“Inevitably such a system is inflexible,” Wilson says. “It doesn’t adapt well to change.”

Then there’s the danger of autocrats believing their own propaganda.

“He’s surrounded by sycophants who are worried about giving him bad news,” Wilson says. “He’s probably clever enough still to realise that it’s useful to him to have (media) who will give him the bad news.”

But there’s bad news aplenty. Change is coming.

“The great irony here is that at the very time when Putin has won, his enemies are in disarray, at this very moment of his triumph, suddenly out of nowhere, come two unforeseen factors, completely unforeseen turns of events,” Wilson says. “One of them is COVID. And one of them is this sudden attack, which he’s finding very difficult to counter from this courageous man called Navalny.”

Revelations of opulent palaces, mistresses and institutional corruption are surging through the nation. Meanwhile, retirees are facing cutbacks to their pensions.

“This is a highly dramatic moment in Russian history,” Wilson says. “We’ve seen it before. Individuals of great courage and moral fortitude, putting their life on the line, in the name of a more humane, a more civilised Russia, a less corrupt Russia.”

Putin’s brand of authoritarianism is undergoing a stress test.

“Navalny is a Putin creation,” Wilson says. “And the Navalny movement is a Putin creation because he hasn’t been flexible.”

Protests have been widespread and persistent.

“It would appear at this stage that Putin doesn’t know how to neutralise them,” Wilson says. “What he’s doing is trying to decapitate them, take out Navalny by putting him in prison. Take out his entourage … But what of the 10, 15, 20 per cent of the population that are disillusioned and alienated from this now sclerotic system? How will they act? We just don’t know.”

CHINA DIVIDED

Xi’s grip on power looks firm. Dissenters face ‘re-education’. Enforcers permeate every aspect of society. Artificial intelligence monitors everything from shopping lists to travel habits and social media posts.

While his authoritarian demands are turning the wider world against him, Xi’s security appears assured at home. His combination of censorship, surveillance and intimidation are working well.

But authoritarians inevitably make everything about themselves.

And that’s their fundamental weakness.

“Never say never when it comes to something like this,” Dr Mattingly says. “With that caveat, I do think that he’s done enough that it makes it really hard for someone to launch a successful coup against him.”

Authoritarians often find public acclaim can quickly turn to public disdain.

“Some either military or economic misadventure could turn the elite officer corps against Xi Jinping,” Mattingly says. Such a disaster could sour the attitude of supporters within the Party. It could turn the populace against him.

“(There’s also) military misadventure, say like an invasion of Taiwan that goes really poorly. You could imagine that could end up reflecting poorly on Xi Jinping in a way that might make some officers mad. But I think that those are two pretty unlikely events.”

The one remaining weakness remains to find Xi’s successor.

“What will this succession struggle look like? Is this a transition from a personalised autocracy back to collective rules? I think that the Party needs to watch out, and here is where the role of the military could become super important.”

UNITED THEY STAND?

The West has woken up to the global ambitions of both Xi and Putin. It’s beginning to push back.

Sanctions have been applied after Russia invaded Crimea, Ukraine and Georgia.

International coalitions are forming against China’s ambitions in the Himalayas, and the East and South China Seas.

But there’s a problem.

The two autocrats are co-ordinating their efforts.

Their backgrounds may be vastly different. But their circumstances are very much the same.

And resistance from the West is driving them together.

“A hard Russia-China alliance … would wed Chinese dynamism with Russian natural resources into a potent threat to dominate Eurasia,” warns Council on Foreign Relations analyst Thomas Graham and Columbia University professor emeritus Marshall Shulman.

Russia and China already co-ordinate their actions against the United States. They both support countries hostile to the United States, such as Iran. They conduct military exercises designed to counter US capabilities. They oppose norms undergirding the US-backed liberal international order.

That collaboration continues to grow.

Xi and Putin see kindred spirits within each other. At the very least, a desire to maintain power.

And that means maintaining appearances of being strong.

“As they draw closer economically, technologically, militarily and diplomatically, and their co-operation in each of these spheres crosses new thresholds, their combined weight in East Asia and across Central Eurasia swells the challenge far beyond that posed by either alone”.

How can this be countered?

“Success requires subtlety and patience,” the academics write. “The two countries’ political systems, the character of their leaders, the complementarities between their economies, and the parallels in their foreign policy agendas create a natural basis for what they describe as a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership of co-ordination’.”

But there are historical grievances and strategic differences between the two nations.

“Nuanced policy designed to exploit this reality would minimise the risk that a “strategic partnership” will congeal into a hostile anti-US alliance.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel

Originally published as Russia v China: One thing Putin and Xi both fear