Rio Tinto found one of the world’s rarest birds within the bounds of its WA copper-gold mine

Rio Tinto has adjusted its plans for Australia’s next big copper-gold mine after the shock discovery of one of the world’s rarest birds: the night parrot.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Rio Tinto has redrawn its plans for Australia’s next big copper-gold mine after the shock discovery of one of the world’s rarest birds within its project perimeter.

The night parrot, feared extinct for more than a century, has been detected at Rio’s Winu project – dubbed the copper whopper – in the Great Sandy Desert in Western Australia.

Rio has cut all identified night parrot habitat from the project’s development envelope to minimise any possibility of disturbing the critically endangered bird.

The call of a lone night parrot was detected in an area Rio had earmarked for a borefield, some distance away from the mine.

No one has seen the bird, which emerges at dusk to feed, but it was detected by audio monitoring of the site. This happened in mid-2024 after no calls were picked up in the previous 2500 nights of monitoring.

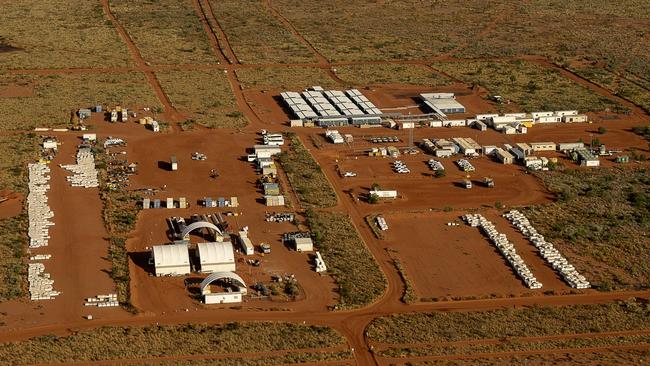

Winu is regarded as mid-size mine by Rio’s global standards as it banks on growing demand for copper as part of the electrification megatrend. The preliminary mine plans involve a development footprint of almost 40,000 hectares in an area about 320 kilometres east of Port Hedland.

Rio rushed to boost its exploration footprint in the region from 1000 square kilometres to 12,000 square kilometres after making the Winu discovery in 2017.

The folklore around the discovery made on the back of three drill holes includes that Rio’s exploration team on the ground were in such a rush to lodge tenement applications that they used their own private credit cards.

Rio had invested $US438m in Winu by June last year and remains in talks with two traditional owner groups – the Nyangumarta and the Martu – about the mine development.

In December, Rio unveiled a joint venture deal with Sumitomo with the Japanese conglomerate agreeing to pay $US399 million for a 30 per cent equity stake in the project.

Rio’s environmental team started monitoring after setting up camp at Winu back in 2018, but found no trace of the night parrot until last July.

Rio’s Winu Health, Safety and Environment Business Partner, Chris Eason, said the bird had been detected in an area of old growth spinifex.

“Old growth spinifex is really important. The country around there gets a lot of fires from dry lightning strikes and so what tends to happen is the spinifex burns out and regrows,” he said.

Mr Eason, who is overseeing the night parrot study program, said the area where the bird was detected had some natural fire defences.

“The spinifex has the opportunity to grow for 10 to 15 years and so you have these really big clumps that offer protection for the night parrot. It can burrow in and roost in that spinifex,” he said.

“It’s pretty hard to find. People have been looking for the night parrot for decades … they thought it was extinct at one stage. Everybody is excited about the opportunity to learn more about it, and opportunities to improve the survivability of the species.”

Rio is confident the mine can go ahead without disturbing the bird. The company is eyeing production of up to 10 million tonnes a year to start with and further expansions subject to environmental and other approvals.

The night parrot has been detected on Martu country slated for infrastructure to support the operations, with the mine itself on Nyangumarta country. Both traditional owner groups are new to dealing with a mining company and Rio has flown community leaders to its Oyu Tolgoi copper mine in Mongolia.

Rio confirmed it had recorded a night parrot with a national authority on the species, Nick Leseberg, and then notified the Martu and Nyangumarta, and relevant government authorities.

The company revised its water drilling program and cut the relevant area from its development plans. Although only one night parrot was picked up within the original development footprint, monitoring suggests there are other birds to the south.

“The only reason we go in there now is to keep collecting more environmental science data, not for any other reason,” Mr Eason.

“Within our development envelope, it’s only a small portion of the thousands of hectares.

“We’re not going to clear any habitat, so then it becomes about indirect impact, such as noise, vibration and dust. We’ve modelled all of those, and for example, noise from the mine doesn’t get anywhere near that habitat area.”

In revealing the bird’s discovery on its website, Rio said it used aerial photography and helicopter surveys to determine the extent of the potential night parrot habitat with on-ground surveys with Martu rangers.

The on-ground surveys also looked for the bird’s possible roosting sites.

Terrance Jack, a heritage co-ordinator for the Jamukurnu-Yapalikurnu Aboriginal Corporation which oversees Martu’s exclusive native title lands and rights, has been organising ranger teams to go out with Rio crews.

“It’s good to do that two-way learning. It gives our rangers experience with whitefella science that can get them more work, and Rio gets to learn about the country they’re working on and can be sure they’re doing the right thing,” Mr Jack said in comments published by Rio.

Scientists believe the night parrot was once found in arid zones across Australia but that any survivors are now limited to desert areas in Queensland and WA.

Rio’s sensitivity under present chief executive Jakob Stausholm marks a turnaround from its previous attitudes to cultural heritage which were exposed when it blew up rock shelters at Juukan Gorge five years ago, necessitating an apology to traditional owners and a cultural overhaul.

Originally published as Rio Tinto found one of the world’s rarest birds within the bounds of its WA copper-gold mine