Lessons Australia must learn from Taiwan’s transition to wind-powered generation

Australia has placed offshore wind at the heart of plans to transition to a renewable future. To meet those goals, Australia will need to learn from Taiwan.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Spanning nearly 200m above the ocean surface, rows of turbines spin slowly to generate the electricity that powers the homes of much of Taiwan’s near 24 million population.

Taiwan was one Asia’s easiest adopters of offshore wind and moving early has paid off.

Pushed by President Tsai Ing-wen, offshore wind was placed at the heart of plans to secure Taiwan’s energy independence and meet net-zero carbon ambitions.

The country has grown from 500MW in 2020 to a target of 5GW by 2026, providing about 20 per cent of the country’s energy needs. By 2035, Taiwan wants to install more than 20GW of offshore wind capacity, making the country that once had to import 98 per cent of its energy self-sufficient and on the cusp of reaching its net-zero aspirations.

Although years behind, Australia hopes to follow Taiwan’s lead and position offshore wind at the heart of plans to replace coal, which is still the dominant source of this country’s electricity, federal Energy Minister Chris Bowen said.

“We are now, I think, the world’s key – if not top three – market for offshore wind. Every single big developer is taking it seriously. It is a big part of my agenda,” Mr Bowen told the Australian Clean Energy Summit this week.

The ambition has lured a plethora of some of the world’s largest renewable energy companies to seek licences to develop in Victoria. This has initially buoyed confidence that a new industry capable of seamlessly compensating for the demise of coal is about to be unleashed.

But for Australia to achieve success, Orsted Taiwan general manager Christy Wang said it must learn from the successes and failures of its regional neighbour and balance aspiration with realism.

“You cannot underestimate the complexity of the offshore wind business. These turbines take an enormous amount of effort, working hand-in-hand with technicians, suppliers and design teams to overcome the weather and sea bed conditions,” Ms Wang said.

Orsted – the world’s largest offshore wind developer – is one of more than three dozen seeking permission to build in Victoria’s Gippsland, which has quickly emerged as the epicentre of Australia’s offshore wind industry.

Developers have been lured to Victoria by Victoria’s ambitious plans and near ideal conditions.

The wind strength and consistency are high by international standards around Victoria, and the state has a large area of shallow ocean less than 60m deep that is perfect for wind turbine platforms fixed to the seabed. It’s a more mature and lower-cost technology than floating turbines that must be used in deeper waters.

To tap this resource, Victoria in 2022 said it wanted offshore wind to provide 2GW of electricity to its grid by 2032, helping replace coal-fired power generators which are heading for the scrap heap. Capacity would double within three years and then reach 9GW by 2040.

For all of Taiwan’s successes, it is behind on its 2025 target as Covid-19 quarantine measures and small policy missteps caused Taipei to struggle to meet its own targets, Taiwan cabinet spokesman Lin Tze-luen told The Australian.

Potential delays would be extremely consequential for Victoria and Australia’s second largest state would be in a precarious position as coal-fired power stations, which provide the bulk of the state’s electricity, are set to close.

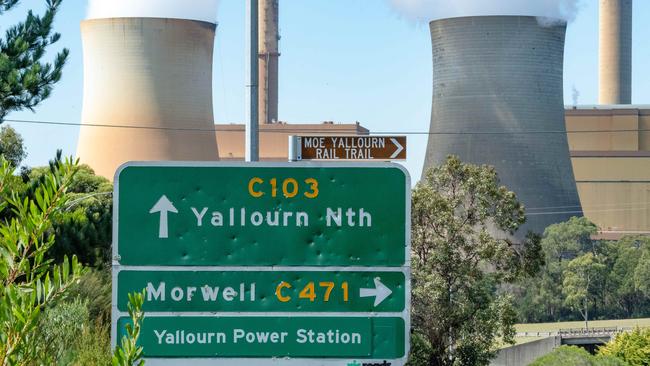

EnergyAustralia’s Yallourn coal power station – Victoria’s second largest and which provides about 20 per cent of the state’s energy needs – will close first in 2028.

Loy Yang, Victoria’s largest coal generator and Australia’s biggest polluting power station, will follow in 2035.

With Victoria so invested in offshore wind, policymakers will need to ensure they avoid the policy missteps and self-inflicted wounds of Taiwan.

Taiwan’s success in offshore wind was curtailed when the government imposed more stringent local content requirements on future developments, resulting in stopping several notable foreign heavyweights – including Orsted – from participating in recent auctions to develop new projects.

With muted interest, Taiwan has been forced to consider watering down the requirements on how much suppliers have to manufacture locally to qualify.

Australian policymakers will need to heed the lessons or risk them fleeing to alternative markets, Orsted head of market development Australia Albert Quan said.

“It will be important for the government to provide flexibility in local content, to enable developers to maximise the local supply chain opportunity while drawing on required global capability, to ensure projects can be delivered within targeted time frames and reasonable cost” said Mr Quan.

Victoria is expected to reveal its local content requirements in the third quarter of the year when it is scheduled to release the much anticipated information on contracting and local content information to would-be developers.

Victoria and Australia can ill afford to get the design wrong, as developers are not short of alternative markets.

Japan, which has set an ambitious target of 10GW by the end of the decade, and South Korea, have set more ambitious targets than Australia, which demonstrates the lucrative returns on offer to offshore wind developers.

Competition was encapsulated by the demand for vessels to install the wind turbines, Ms Wang said.

A so-called wind turbine installation vessel typically has a buoyant hull fitted with a number of movable legs, capable of raising its hull over the surface of the sea, but there were fewer than two dozen of them in operation just a few years back.

To finish the next stage of its Taiwanese development, Orsted must install only 14 more turbines, but it will take possession of one of just a handful of vessels capable of installing them in the fourth quarter of 2023 when winter conditions could make conditions unsuitable for installation.

Miss the window, and Orsted will be forced to wait until the vessel is next free.

But competition is intense, and some offshore wind developers are taking the unusual step of contracting the use of these vessels for years. German developer RWE earlier this year announced a five-year contract for two installation vessels.

With lofty transition goals, Australia is going to have to find a way of developing its offshore wind industry that even the most ardent critics of the country’s transition ambitions accept.

Coal generators are under intense social and economic pressure and many of them are approaching the end of their lifespan. While Australia has seen a wave of onshore wind and solar projects, these cannot match the scale of offshore wind developments.

Offshore wind has a different generation profile compared with onshore wind, typically producing electricity most in the evening or overnight.

But scale comes at a cost. Industry insiders accept the majority of offshore wind developments will cost more than $10bn each, possibly more if the project adopts a floating turbine which is not fixed into the ocean seabed.

For a project to be economically viable, developers are going to have to be offered lucrative, guaranteed returns.

Developers will again be keen to see the detail on Victoria’s proposed model. Victoria has indicated it will proceed with a contract-for-difference model, in which subsidies for renewable energy generation are awarded through a competitive auction process.

But Australian energy experts said they worry the model will not reflect the risk profile of offshore wind.

“Offshore wind is priced similarly to onshore wind. But offshore has a different risk profile, reflecting the unknowns on geology, and I just don’t know how the financials stack up, without taxpayers being on the hook for generation,” said one senior energy executive.

“It may be the only way we can reach the renewable energy targets but it is going to cost.”

Orsted contributed to the funding of the trip by the reporter

More Coverage

Originally published as Lessons Australia must learn from Taiwan’s transition to wind-powered generation