How we will all pay for the bad behaviour of the banks

IF you think the appalling behaviour of banks doesn’t affect you, you’d be wrong. We are all going to feel the pain.

Investing

Don't miss out on the headlines from Investing. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE Banking Royal Commission has been a delight for anyone who wishes to see justice done in the financial sector. Across the plush-carpeted corporate offices of major financial institutions, heads are rolling.

The CEO of AMP is the highest profile example. The boss of the huge asset management and insurance firm left his post this week, as it was revealed that AMP had lied to the corporate regulator and charged customers for doing nothing at all.

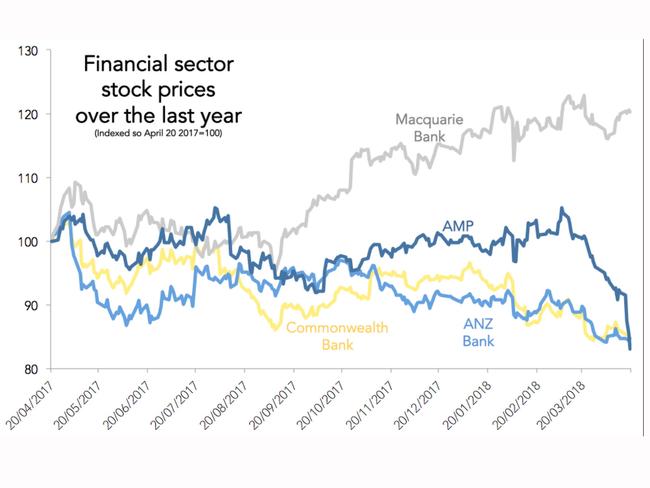

Executive departures are a sign of change and renewal. They plant seeds of hope for the future. But in the meantime, the stock prices of many of these major financial institutions have been falling. You can see AMP’s recent plunge in the graph below.

These stock price falls across the financial sector (Macquarie Bank being one notable exception) are a sign that banks will have less leeway in future to do what they want with the rules. That is undeniably good. But it comes with a cost too, and there is no point denying it.

Finance is a huge part of the Australian economy these days. It makes up around 35 per cent of the top 200 Australian stocks. Anyone with some superannuation is likely to have it invested partly in finance companies.

For example, if you have your money in the Balanced Fund at Australia’s largest Industry Super fund, they put around a quarter of your money into Australian shares. That will include shares in the banks. So when Australian stock prices fall, your super savings shrink slightly.

ONE IN, ALL IN

AMP is an especially good example of how the corporate sector is a part of everyday people’s lives. The company started off as a mutual fund, meaning it was a cooperative essentially owned by the people who had insurance policies there. If you bought an insurance policy, you were in a sense a part owner.

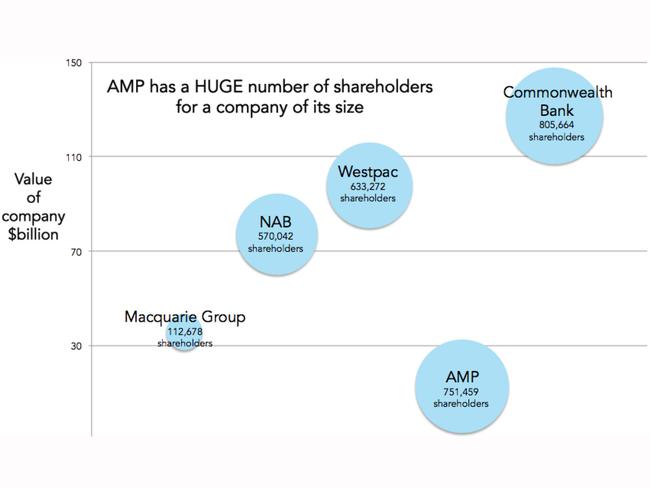

When AMP became a public company in 1998, a whopping 88 per cent of those regular people chose to become stockholders. That turned thousands of people into stock market investors overnight. Some have never sold and to this day, AMP has an amazingly large number of stock holders, as you can see in the next chart.

AMP has seven times as many shareholders as Macquarie Group Limited, even though Macquarie is worth three times as much. AMP has more shareholders than NAB and Westpac. It has only slightly fewer than the mighty Commonwealth Bank, which is worth ten times more than it and is Australia’s most valuable company, and one of the most valuable companies in the world.

So when AMP’s corporate misbehaviour comes to light, the impact falls especially widely.

GRIT YOUR TEETH AND BEAR IT

When we punish banks, we also punish ourselves. Our society allowed banks to do what they did, and gained from the way they operated. When we crack down, we lose the gain.

Please do not interpret this as suggesting we should go easy on the banks. My view is quite the opposite. I want justice done. I raise these points only to emphasise how challenging it will be. Meting out justice is costly. It hurts. This is one reason why big institutions doing the wrong thing get away with it for so long — they think the misbehaviour is so woven into the fabric of society we can’t rid ourselves of it.

When we punish a single low level criminal, we don’t feel the pain, just the justice. But when we crack down on corporate misbehaviour that is widespread and institutional the lash of punishment lands on all of our backs.

If we want to insist on good behaviour, we have to accept the pain that will follow. We have to hold our nerve and accept the consequences of justice.

Jason Murphy is an economist. He publishes the blog Thomas The Think Engine. Follow Jason on Twitter @Jasemurphy

Originally published as How we will all pay for the bad behaviour of the banks