From scandals to soaring share price – CBA’s remarkable comeback from Hayne inquiry

CBA’s string of scandals in the early 2010s makes Qantas’ current reputational issues look like minor turbulence. Half a decade later, CBA has emerged strong.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Commonwealth Bank’s string of scandals in the early 2010s makes Qantas’ current reputational issues look like minor turbulence.

Back then, the nation’s largest lender was rigging in its favour a key interest rate that sets the banks’ cost of funds, alongside several other lenders. Media reports were also buzzing with transgressions at CBA’s wealth management, insurance and superannuation units.

Then, in August 2017, a bombshell revelation came from the financial crime regulator, Austrac. Widespread anti-money laundering failures allowed criminal syndicates to launder money through CBA deposit machines.

The charge – for which the bank was later hit with a $700m fine, a record at the time – sparked a wave of public condemnation, including from the then prime minister Scott Morrison, that triggered the 2018 royal commission.

But half a decade after Kenneth Hayne, the former judge who led the inquiry, scolded banks in the final 1133-page report and called on them to stop putting their profits ahead of customers, CBA has made a remarkable comeback.

The bank amputated its most problematic units, paid more than $3bn in customer remediation, stepped up technology investment to improve advocacy and satisfaction levels among customers, boosted its market share and now commands a record stock price, making it one of the most expensive banks globally.

The turnaround shows that if big moated companies like Qantas – which faces accusations of gouging customers and of intentionally selling cancelled flights, and illegally firing workers during the pandemic –play their cards right, they too can look forward to a time when shocking headlines are forgotten.

“CBA are not perfect, but we could look at their example as a good case study in how there have been improvements, and how financial services firms and banks can improve,” former ASIC chairman James Shipton tells The Australian.

“It is a good example that it can be done, and it can be done profitably. What we then need is regulatory infrastructure that incentivises and disincentivises, in an appropriate way, CBA-type turnarounds.”

Taking the helm of ASIC just as hearings into financial misconduct began in February 2018, Shipton was thrust into the spotlight later that year to face tough questions at the inquiry about the underfunded regulator’s past performance in policing the banks.

Some argue a key long-lasting effect of the royal commission has been a reduction in profitability for the banks.

The inquiry scared them out of wealth management – a capital-light business but the source of a large part of their remediation bill – and almost singularly into retail banking, intensifying competition.

Return on equity (ROE) at CBA in 2017, the year the royal commission was announced, was 16 per cent. That fell to 12.5 per cent in 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic pushed them further down to 10.2 per cent and 11.5 per cent in 2021.

That is not to say the bank, the largest member of Australia’s four-bank strong oligopoly, is not very profitable still. Suffice to look at the 20-times forecast earnings its shares command today as evidence of the risk-adjusted returns it is expected to deliver.

“The major banks still dominate market share in retail and commercial banking and their returns on tangible equity are now in the low and mid teens, which is a better return than the single-digit returns earned by a lot of the big banks globally, even if it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison,” says E&P Capital banking analyst Azib Khan.

“But their ROTE used to be higher and now they are lower, partly because wealth management has been divested.”

The pandemic was a big help in restoring trust among customers, allowing banks to leverage ultra cheap money sponsored by the government to help homeowners and businesses weather the storm.

Then the RBA’s aggressive interest rate increases to control high inflation after the pandemic delivered CBA a record $10bn profit last year. Yet, return on equity levels remained well below those scored before the inquiry at 14 per cent.

The focus on mortgages has led to higher competition for the same commoditised loans, which has pushed net interest margins lower for all banks. And the downward profitability trends are worse at CBA’s smaller peers across the sector.

Stricter capital rules implemented after the 2008 global financial crisis forced the Australian government to guarantee wholesale deposits have discouraged non-mortgage lending by penalising all but the safest home loans.

That, alongside the royal commission’s influence on strong responsible lending practices, has driven a de-risking of banks’ balance sheets. But it also further intensified competition for higher-quality home loans.

The consequences have been serious for the smaller, regional banks, and the credit union and building societies, where profits are shrinking to such an extent that many question their ability to keep up with the technological and compliance investment needed to compete with the likes of CBA.

Mr Khan also argues that while CBA and the other major banks could be characterised as “safer” or “stronger” five years after the Hayne report, the riskier loans they are forgoing are being sourced by lenders to which regulators pay much less attention, increasing risks in the broader financial system.

“It resulted in the shadow banking sector taking on more risk, and that is a far less regulated part of the market. That’s arguably a greater threat for financial stability,” he says.

Selling compliance-heavy and scandal-ridden units to other insurers or wealth managers was the banks’ almost immediate response to the royal commission, including at CBA, which unloaded about $13bn worth of non-core businesses.

But the big banks also had to change their previous “caveat emptor” mindset, and submit to the moral pressure brought in by the inquiry to act in the best interest of customers, given the huge power disparity with customers.

“The royal commission addressed a number of matters including the imbalance between the banks and their retail customers,” says Nicholas Moore, former chief executive of Macquarie Group.

“This has been accepted by the banks and changes have been put in place to protect the customers including ensuring the products offered are in the interests of the customers.”

Moore was another key witness of the inquiry in late 2018, when he was asked to testify about how the silver doughnut fixed problems at its own private wealth division years earlier.

He also led the Financial Regulator Assessment Authority’s review into the banking watchdog, APRA, and of certain areas of ASIC, last year, which was in response to the Hayne report’s recommendations.

By the time the two-volume Hayne report was published on February 1, 2019, the banks had already begun their transformations. They vowed support for its 76 recommendations, and the impact was swift.

Six days after the report’s publication, National Australia Bank had its two most senior leaders, CEO Andrew Thorburn and chairman Ken Henry, resign under the weight of its criticisms.

Their exit propelled former NAB director Phil Chronican as interim chief executive and chairman, before Ross McEwan was appointed CEO later that year.

The arrival of the well-liked duo marked a turning point for the bank, revitalising it and reversing its longstanding reputation as an underperformer.

But the change in mindset and culture has perhaps been most palpable at CBA, under chief executive Matt Comyn and former chairwoman Catherine Livingstone, who retired in 2022.

CBA promoted Mr Comyn to succeed Ian Narev as CEO in January 2018, two months after the misconduct probe was announced by the government in November 2017.

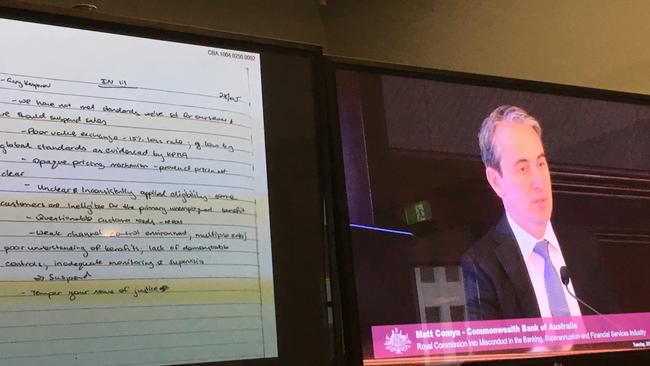

Testifying at the inquiry in late 2018, Mr Comyn famously revealed Mr Narev had told him to “temper your sense of justice” when he, as head of retail banking, lobbied but “was insufficiently persuasive” to convince him to scrap consumer credit insurance products.

This was despite a 2015 internal audit revealing tens of thousands of CBA customers had purchased junk insurance when they were unemployed, as that made them illegible to make a claim.

“As challenging as the royal commission process was, CBA is a simpler, better bank as a result. We believe that is also reflected across the banking sector as a whole.” says Daniel John, the bank’s head of group public affairs and external communications.

“We have implemented all of the commission’s recommendations which applied to us … (and) made significant changes to our entire business, introduced stronger policies and processes, improved our culture, and prioritised customer interests.

“Above all, we recognise the importance of the trust that our millions of customers place in us every day.”

To be sure, complaints to the financial authority are ballooning amid a surge in banking scams and higher cost-of-living stress. And even if some have praised the big four’s improvements in how they support customers in hardship, remediation payments remain an ongoing feature of banking results.

Mr Shipton, who is now a senior fellow in the Melbourne School of Government at the University of Melbourne says the bank’s turnaround was a result of good leadership, but the changes must endure.

“From the senior most leadership of CBA, there was a genuine willingness to learn lessons and make changes,” he says.

“The challenge for CBA is, can these changes endure? And that’s where you need regulatory settings in place to incentivise the next generation of leaders at CBA and elsewhere.”

But Mr Shipton argues work on many of the inquiry’s key recommendations and lessons remains unfinished.

“The risk is that we’re just going to keep the cycle of royal commissions every five to 10 years, as opposed to having responses structured and institutionalised so that we don’t have to have a cycle of royal commissions.”

“The worrying thing is that we don’t have the regulatory architecture in place after the royal commission that we should have, and many of the ideas of Commissioner Hayne actually weren’t fully adopted, or have been forgotten.

“Which means, history is doomed to repeat itself.”

One of the key ignored recommendations was the abolition of the trailing commissions the banks periodically pay mortgage brokers for the loans they arrange. Instead, Commissioner Hayne said, borrowers and not lenders, should pay a fee for service.

The former Morrison federal government first supported their removal but back-pedalled that support before the May 2022 election. Efforts to free up credit by watering down responsible lending obligations and placing the onus back on borrowers also ended when the previous government lost that election.

“Brokers continue to receive upfront and trail commissions that are paid by the lenders, not by the borrowers. And so the fact that the government didn’t take on the royal commission recommendation cemented the status quo and has resulted in brokers increasing share,” Mr Khan says.

This entrenched power is evident in the shift of lending sources. Brokers, whose remuneration structure means they get paid more for bigger loans, now capture roughly $7.5 for every $10 borrowed, compared with just 55 per cent before the inquiry.

That, however, is not the case at CBA, which has chosen to invest in its proprietary infrastructure to sell more loans directly to customers, through branches, mobile bankers and digital channels.

In fact, many argue a key reason for CBA’s relative success compared to its peers since the royal commission is its consistent investment and focus on technology – a strategy initiated by management generations ago.

“CBA has been able to build on its very strong brand and customer base with a successful focus on developing and implementing technology which has improved its systems and processes over many years,” Mr Moore says.

More Coverage

Originally published as From scandals to soaring share price – CBA’s remarkable comeback from Hayne inquiry